|

[Back to Chapter 7]

CHAPTER EIGHT

FULFILMENT AND THANATOS

[1887 - 1907]

|

|

Death is the separation of a

duality, and effects no change in the spirit, morally or intellectually.

(Alfred Russel Wallace)

|

|

|

THIS last period in

Massey's life, although almost as productive as in previous sections,

was mainly a period of consolidation of ideas and completion of purpose.

He had refuted many of his previously held opinions, published fifteen

years earlier in Concerning Spiritualism, and extended his

research-based conclusions to anti-orthodox Christianity. His

published lecture series demonstrated those issues very fully, as did

his appearances at public meetings. A series of six at St George's

Hall, Langham Place, commencing on 12 June 1887, clearly stated his

position. Titles included ‘The mystery of Paul, "Apostle of the

Heretics", and not of historic Christianity', and 'Christianity, an

anti-Spiritualistic system’. He had, in broad terms, clashed with

the Christian Spiritualists, whose undeveloped mediums preached nothing

but Christianity through ‘spirit guides’, which same 'spirits'

continually endorsed exploded myths as facts. He maintained this

position in his lectures, when he stated, ‘phenomenal Spiritualists who

go philandering with the fallacies of the Christian faith, and want to

make out that it is identical with Modern Spiritualism, have to face the

great indubitable fact that Historic Christianity was established as a

non-Spiritualist and an anti-spiritualistic religion.’[1]

During these lectures he had occasion again to refer to the presumptions

of the Christian Spiritualists, this time on remarks made by Alfred

Russel Wallace. Wallace had been stating that Spiritualism alone

could reconcile the Bible with an intelligent belief, particularly in

regard to the miracles which, as facts, need not be explained away.

Massey was astounded by this position taken by one of the foremost men

of science and co-contributor with Darwin. Wallace's opinion, he

said, was unscientific, false, and based on the confusion with

symbolical representation. It was the pre-Christian, Gnostic

religion that based immortality or continuity of existence upon the

evidence of abnormal phenomena and clairvoyant vision. The

resurrection of the Christ of historic Christianity was physical, and

you cannot demonstrate a spiritual continuity by means of a bodily

resurrection. Mythical miracles could not be converted into

spiritual phenomena.[2] With the much firmer

stance he was taking on religious origins, particularly Christianity, he

commenced to use the term ‘Neo-Naturalistic’ in place of

‘Spiritualistic’, as he claimed that Spiritualism was a newer, larger

Naturalism.

Since the publication of his

Natural

Genesis he had been engaged at intervals on a recast version of

his work on Shakespeare's Sonnets. In this, he hoped to give a

closer clinch to his conclusions, complete his case, and leave a

permanent memorial of his love and admiration for Shakespeare the Poet

and Man. The Secret Drama of

Shakspeare's Sonnets

was published in 1888 and restated his earlier premise that the sonnets,

partly personal and dramatic, require regrouping in order to maintain

the series. A section of ‘Biographia

Literaria’ included the Earl of Southampton, Lady Penelope Devereux,

Shakespeare, and Francis Bacon. This latter claimed Massey's

attention on account of Ignatius Donnelly's recently published book

The Great Cryptogram. In 1856 Putnam's Magazine

had printed Delia Bacon's opinion that a number of well-known persons

could have authored Shakespeare's plays. She followed this in 1857

with her book on the theme, The Philosophy of the Plays of

Shakespeare unfolded. This hypothesis received some support,

as well as opposition. William Henry Smith, politician, published

his

Bacon and Shakespeare: an Inquiry… in the same year. Later,

another group who were advocates of the ‘Oxford Theory’, promoted Edward

de Vere (1550-1604), Earl of Oxford, as the author. The Baconians

gained some ground following the formation of the Bacon Society in 1885,

and the publication of Donnelly's book that proposed a secret cypher

encoded in Shakespeare's plays. That cypher was supposed to reveal

political intrigues and scandals of the time.[3]

Donnelly was also a supporter of the theory of ‘Atlantis’. Massey

devoted a section of his book in demolishing the theory, which received

approval by the reviewer in

Punch, under the heading:

|

DOWN ON DONNELLY;

Or, Crushing the Cryptogram.

A POET on the Poet! That should herald

A real Champion's advent. Go it, GERALD! …

IGNATIUS now, the “Moon-Raker” gone frantic,

Who hunts for mare's-nests under the Atlantic,

And SHAKESPEARE'S text, is naturally stilted,

But under MASSEY'S mace he must have wilted …

Your monumental book's a trifle bulky

(Five hundred pages turn some critics sulky,

My massive MASSEY), but 'tis full of “meat”,

And sown with song as masculine as sweet …

Whilst all will track with grateful heart and eye

Your slaughtering of that colossal Sham

Egregious DONNELLY'S Great Cryptogram![4] |

St James' Gazette also approved, saying ‘In

justice to Mr Massey, it must be said that many of his most important

conclusions have been stolen—or let us say ‘conveyed’—by some critics

who are loudest in repudiating his dramatic interpretation.’[5]

Amos Waters, reviewing the 1890 edition in Watt's Literary Guide,

praised the intricacies of research and excellent tissue of relevant

detail. ‘Massey's chivalrous and monumental book will arise in the

average reader added joy, new light on Shakespeare's sonnets, and a new

love for Shakespeare the man.’[6]

A number of years later, a correspondent in the

Times Literary Supplement wrote concerning Marston's reference to

Drusus, in his The Scourge of Villanie 1599, which suggested

there had been a revival of Romeo and Juliet in 1598. After

reading Marston's book, Massey had proposed that Drusus was an allusion

to Shakespeare, which prompted the disagreement of Dr C. M. Ingleby.

The correspondent was surprised that Massey had not presented all the

evidence contained in Marston's book, which would have made a stronger

case for his proposal.[7]

The last article he wrote for a journal was ‘Myth

and Totemism as primitive modes of representation’. As with

his published lectures, it was a summary of sections in his main works,

principally The Natural Genesis, and therefore more explicit.

His thesis proposed that as primitive mythology belonged to external

nature, the actors in the drama were the elements themselves, birds,

animals, reptiles, and not human beings. For example, the

elemental conflict of light and darkness was portrayed by two birds as

zootypes of the air. In Egypt, this was the golden hawk of day and

the black vulture of night, and for the Australian aborigines, the eagle

and crow. Later in development, the phenomena were interpreted

using human beings in place of zootypes, as in the brothers Cain and

Abel, Sut and Osiris, etc., who were always working to slay each other.

Thus once the powers were humanised, and related as history, the myths

became misrepresented, and considered as savage, senseless or obscene.

Particularly so when the first parent in mythology was the dragon of

darkness, or the cow, that brought forth the child of light in Egyptian

mythology. Later in the development her child, who was also her

consort, attains to the fatherhood, when his own mother becomes his own

daughter. Therefore the mother, wife and daughter of, for example,

the Egyptian sun-god Ra, are all one. As a mode of representation

it was natural, the unknown being expressed by the known. As a

modern belief, it is of course false and immoral, and it is the modern

beliefs that misrepresent the ancient myths. In totemism, a nature

power represented by a zootype was adopted as a badge of distinction for

social groups. It was a primaeval coat of arms, extended by blood

covenant, to form a sept, clan, and tribe. Continuing development

extended the totem's blood covenant to the actual powers of the zootype,

considering them as elemental spirits, giving rise in some instances to

human sacrifice and cannibalism.[8] (Appendix

F.)

He continued with some public lectures during 1887

and 1888, mainly in London at the Cavendish Rooms, Mortimer Street, and

at his favourite venue, the St George's Hall, Langham Place, but as a

source of finance they were inadequate for his needs.[9a]

Seasonal lecture tours arranged by agents were held in the winter

months, and that time of year was difficult for him due to chronic

bronchitis. Early in 1888 he was again in debt. His sponsor

for thirty-five years, Lady Marian Alford, had died earlier in the year

so he was compelled to apply to the Royal Literary Fund for a further

grant. The fund gave him assistance in the sum of £80, but it was

quite obvious that unless he could obtain a further source of funding

his next book as well as his whole livelihood would be compromised.

The only way out of the predicament, before his health suffered further

decline, would be to make a final, and hopefully equally financially

rewarding, third tour of America. Therefore he began again to make

arrangements, despite his previous second visit having been interrupted

by illness. The advance list of Evolutionary, Anthropological,

Gnostic and Neo-Naturalistic subjects was the largest he had ever

presented, the recently published series of ten lectures being

supplemented by a further twenty-one. Topics on Zootypology,

Totemism, Fetishism and Sign language were condensed from his published

four volume works. These were augmented by the literary subjects

of Charles Lamb, Robert Burns and Thomas Hood and, additionally to

enhance the sales of his Shakespeare book, ‘The AntiShakspeare Craze;

or, Shakspeare and Bacon,’ and ‘The Man Shakspeare; His Life and Work’.

New Southgate

London N.

August 2nd [1888]

Dear Alfred Bull,

Yours to hand. I was vexed not to have seen you. It was Measles my

children had – and badly too. I have recently announced my intention of

another trip and expect to sail in the Umbria 4 Weeks come Saturday.

Dont know if I can stand your Winter but I must try. Whether I shall see

Chicago or not is more likely to depend on you than anyone I know. But

more of that anon. I have no wish for any further dealings with Cundy.

He served me too badly in the Affaire Column. [?] (Lee pamphlet sent)

When I sent him a Reply he burked it. That is friendship enough for one

life time. I have no great anticipations in Lecturing, on account of my

health, but I have other business. Moreover I shall have 10 Printed

Lectures on Sale this time – may help a little. I send a few Circulars,

but the Lecture List will require a careful handling with the orthodox.

If you should be writing within [?] the time you can address me c/o

Judge Dailey 16 Court St Brooklyn. You might perhaps get me a Subscriber

or two to the Shakspeare Book, five Dollars? It will be out forthwith,

[9b]

With the kindest regards to your Wife and a kiss for the Boy

I am yours

Gerald Massey

Alfred Bull Esq.

The Cunard liner RMS Umbria made its maiden voyage from

Liverpool to New York on 1st November 1884.

Arriving in Boston, he commenced with a series of two

lectures for the Independent Club, at Berkeley Hall on 11 November 1888.

The Boston Herald described him as an elderly gentleman, with

greyish moustache and chin whiskers, and wearing glasses. He read

from manuscript very quickly and clearly, and was received with

approbation by the audience.[10] During his

time in Boston, he stayed with A. E. Giles at Hyde Park, and enjoyed

social evenings with, among others, Theodore D. Weld, the old-time

Abolitionist. Continuing to Providence, Rhode Island, for the 25

November and 2 December, he returned to Boston again for ‘The

Coming Religion’ on 9 December.[11]

During his time in America he hoped to make

arrangements for a new edition of his poetical works, and to sell copies

of his lectures of which he had brought a supply to deposit with Colby

and Rich, as agents. But that lecture in Boston was the last he

gave in America. He received a telegram requesting his urgent

return to England, where his daughter Hesper, described as ‘a beautiful

girl of eighteen’ who was a sufferer from tuberculosis, had become

seriously ill. She died on 3 March 1889.

|

We called her Hesper; for it seemed

Our Star of Eve had on us beamed,

Like Hesper, from the Heaven above,

To latest life a Lamp of love. . .

Beyond the Shadow of the night

That parted us, she lifts her light

To beacon us the Homeward way,

Where we shall meet again by day.

The Star of Eve may set, but how

It shines, the Star of Morning now … |

That same year Massey compiled a two volume edition

of the greater part of his published poems, as

My Lyrical Life. In the

explanatory preface he

considered that a lyrist has the liberty of the dramatist in

representing other characters, situations, or moods which may not be

personal to the writer. Hence Robert Browning's descriptive title

of ‘Dramatic Lyrics’. Many of Massey's lyrics are dramatic also,

in that sense. His dramaticism extended to patriotic and political

affiliation, and causes which were unpopular at the time. Women's

liberation movements would have been proud of him, when he considered

that the Fall of Man was being gradually superseded by the Ascent of

Woman, and he regarded the first necessity was for them to obtain

parliamentary franchise. They could then hope to stand upon a

business footing of practical equality with men. Of his poems, he

had no extravagant estimate of their value which, some twenty years

earlier he had ceased to regard as the special part of his literary

life. He had been referred to as a poet who had not fulfilled the

promise of his early achievements; yet had received testimony that his

poems had done welcome work, if only in helping to destroy the tyranny

of death, which made so many mental slaves afraid to live. The

Athenæum, who could be relied upon in giving fair appraisals of his

poetical works, treated him quite kindly. After commenting that

his name in recent years had been less familiar than it deserved to be,

it referred to some over-exuberant rejoicings from authoritative critics

that had been quoted in the introduction. It agreed also with

Massey's own comments that in general, the range of his poems was

limited. Not over happy with his political ‘Home Rule’ advocacy,

the reviewer recommended that the reader turn to the reprints of his

first volumes and be soothed by their idyllic, almost holy, graciousness

of domestic piety.[12] The

Saturday Review likened him to an inoffensive and amiable Robert

Buchanan, with the same fluency, the same mastery of the manifest, the

same ease in the obvious, the same sort of creditable approach to

success. Saying that they really liked Mr Massey's Muse, they had

strong reservations on his mixed metaphors and outworn ideas. The

less ambitious he was, the more he spoke through the heart, not the

head, and the more briefly he spoke the more he attained true, though

not lofty, poetry. Although he appeared more at home with domestic

sentiment, they noted as had reviewers in his early days, that there was

too much of the ‘wee shrouds, wee bits, wee graves, wee wifes and other

phrases endearing in the sacred intimacies of home, but unworthy of the

Muse’. Of his

Tale of Eternity they

remarked that they could not believe in the sublime, though he had a

thousand claims on their sympathy.[13] The

volumes however, proved their popularity by raising a second edition the

following year.

That year, 1890, saw the death of another daughter,

Elsie, aged 16 years. She died on the 22 July of peritonitis.

It may have been due to this, and the memory of Hesper's death, that

induced him to move at the end of that year from Southgate to a similar

property, ‘Rusta,’ 266 Lordship Lane, East Dulwich.

|

|

|

Dr Albert Churchward MD., MRCP., FGS.,

PM., PZ., 30º MDU

(Photo: © Jack Chuchward) |

It was about this time ,or perhaps a few years earlier, that he had come

into contact with Dr Albert Churchward (1852-1925), a general

practitioner and high ranking (30 degree) freemason who lived at Erroll

Lodge, 206 Selhurst Road, South Norwood. Born in Bridestowe,

Devonshire, Churchward obtained his medical qualifications from Guy's

Hospital, Brussels and Edinburgh. He was particularly interested

in Ancient Egypt from a masonic perspective. In this connection he

made a particular study of early African and other peoples from a

medical viewpoint in order to research and give support to his theories

that were very similar to Massey's, though in a more restricted sphere.

Like Massey, his theories were not accepted by orthodox anthropologists

and ethnologists at the time, but he held their opinions in scant

regard. Their association may have come about due either to

Massey's public lectures or his published works on religious origins.

Churchward's first book The Origin and Antiquity of Freemasonry

was published in 1898. There was extensive collaboration between

these two men that continued up to the time of Massey's death, and

Churchward's subsequent publications owe more than a great deal to

Massey's ideas. Churchward's main work Signs and Symbols of

Primordial Man is his best known. It can be noted that his

brother was Lt. Col. James Churchward (b.1850), author of controversial

books on

Atlantis. Although Massey was not a freemason, disliking

any form of secrecy, and Churchward had staunch Conservative opinions,

there was sufficient compatibility of interests to produce an enduring

friendship.

As Massey's health during the winter months was

becoming increasingly precarious, the American lectures were the last he

gave to large public audiences, and he restricted himself to smaller

organisations, by invitation. In 1891 a proposal was made to form

a Gerald Massey Society. The promulgator, Mr F. Dever-Summers of

Wandsworth, considered that the formation of such a society would,

through meetings, discussions and the formation of provincial branches,

clear a way through a jungle of false doctrines. Suggesting a

weekly subscription towards the purchase of Massey's and other similar

books to make up a small library, members of any religious denomination

would be welcome. This was seconded with grateful sympathy for

Massey's work, and a proposition that he could then prepare lectures,

papers or articles on subjects relating to the work of the society.[14]

The amount of support received for the proposed society is not known,

but it was never formed. This may have been due to preparations he

was making for the last two volumes of his trilogy on evolutionary

themes. In any case, despite his idealism, he was very wary in

later years of committing himself to anything that did not suit his

purpose at the time, or might interfere with plans already made.

In connection with Massey's earlier opinion on the

unreliability of spirit communication, a correspondent in an issue of

Medium and Daybreak

in 1893 asked if a book written by the medium David Duguid, entitled

Hafed, Prince of Persia, should not be truthful, emanating as it

did from the spiritual world. The book was stated to have been

dictated by a ‘control’ who lived at a time contemporary with Jesus

Christ, and was a witness of his birth and death. The writer

questioned that account, as it conflicted with Massey's argument as an

evolutionist, that these chronicles were mythical. The opinions of

other readers were sought, as embodied and disembodied spirits ought to

be agreed on fundamental truths. The editor, James Burns,

explained that Massey's ‘Christ’ was the immortal part of man, while

‘Jesus’ was the name given to the person who may have suffered and died

as stated in the gospels. They were two very different subjects.

The faculty of mediumship was greatly abused because of the ignorance

and fanaticism of so-called Spiritualists. Had Massey responded,

he would undoubtedly have been more forthright in providing a suitable

answer.[15] Twenty years earlier Massey had

complained about poetry purported to have been transmitted by departed

bards to Thomas Lake Harris, poet, Christian Spiritualist and prolific

author on religious mysticism. On examination, Massey had found

some of Harris' inspiration to contain plagiarism and mental piracy—an

imposture, he stated, from whichever world it originated.[16]

Massey's financial position was reasonable at that

time, but apart from purchasing a small ‘cottage’ of unknown address,

and from which he obtained an annual rent of £35, he ignored

well-intentioned advice regarding any form of monetary investment.

This was ultimately to be an unwise decision. His next move at the

end of 1893 was to a large detached rented property at 11 Warminster

Road, a quiet residential area of South Norwood. In naming the

house ‘Anru’, the Egyptian word for ‘Paradise’, he hoped that move would

be his final address.

Anru, Warminster Road, South Norwood.

From the Bookman, Nov. 1897 (The British

Library).

Massey in his study at Anru.

From the Bookman, Nov. 1897 (The British

Library).

Meanwhile Fabyan, Massey's only son, had obtained a

post as a telegraphist in Bermuda when, following two years in that

country, he became ill and was diagnosed as having pulmonary

tuberculosis. His sister, Hesper, had died of the disease seven

years earlier, and it is possible that he obtained the primary focus

from her. Due to Fabyan's deteriorating condition, Massey's eldest

daughter Christabel then aged 36 went out to nurse him, but he died in

Warwick, Bermuda, on 7 January 1896, aged nineteen.

George Julian Harney's eightieth birthday fell on 17

February 1897. Confined to bed at his home in Richmond due to

severely painful rheumatoid arthritis, he had been contributing articles

until recently to the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle. With

nostalgia he had heard at intervals of the deaths of his Chartist

friends

Thomas Cooper in 1892, and J. B. Leno

in 1894, aged 68. Other leading members of the movement had

preceded them by many years. Bronterre O'Brien, editor of the

Poor Man's Guardian and a founder of the National Reform League,

ended as a shabby, beery loafer in Fleet Street, dying in 1864.

John Arnott, the capable general secretary of the National Charter

Association was seen by W. E. Adams in 1865 half starved, begging in the

Strand (see author's

brief biography), and Ernest Jones

had died in 1869, his earlier political opposition with Harney

reconciled.[17] W. E. Adams, George Jacob

Holyoake, James Linton and Massey were among the few remaining Chartists

who had been active in the revival of the movement. At the end of

1896 the Weekly Chronicle and the

Free Review

promoted a subscription fund for Harney in order to make him a gift on

his birthday. In a letter to Henry Wonfer, secretary to the fund,

Massey subscribed five pounds, and asked for Harney's address so that he

could send him a copy of his collected poems.[18]

Unable to make the visit due to poor health, he arranged for his

daughter, Christabel, to represent him. Two hundred pounds had

been raised for the presentation, the delegates meeting in Harney's

book-lined bedroom. Telegrams and letters of appreciation were

read out, and Mr Stroud, treasurer of the fund, made the presentation to

Harney, pointing out that many of the political changes that he and his

fellow Chartists had so ardently advocated at that time were now part of

the statutes. Harney's name would live on for generations to come.

Harney responded, with references to his early republican days,

confirming that he was the sole survivor of the delegates who

constituted the first Chartist Convention which met on 4 February 1839,

at the British Coffee House, Cockspur Street. The presentation to

Harney was made with only months to spare. He died, in continual

pain from arthritis, the following December.[19]

Massey was now fully occupied with the final part of

his trilogy, helped by his daughter Christabel who typed his

manuscripts. On being interviewed by a young reporter during one

of his more restful days early in November 1897, he admitted that

bronchitis confined him to his house during the winter months, but he

was able to venture out for short distances during the summer, though

rarely went into town. Whilst he was at Ward's Hurst in the late

1860s he had worked a twelve hour day, seven days a week, but allowed

himself now a much looser regime, while not wasting time or energy.

At his desk at 9.30 after reading the Daily Chronicle, he had a

light lunch at 1 p.m. followed by a short nap, then worked until supper

at 6.30, going to bed at 10 p.m. ‘No,’ he said, ‘I don't find my

life monotonous or tedious. The explanation of my health and

happiness is that I do not rely on externals … I never felt younger than

I do now.’[20] The reporter had impressed

Massey with his genuine interest and enthusiasm and, with Massey's help,

was able to interview Alfred Russel Wallace the following month.[21]

Massey wrote a letter dated 9 November to Wallace, expressing the

reporter's desire for an interview:

Dear Alfred Russel Wallace,

I don't know whether you see the Bookman, but it is giving a

series of Sketches based on Interviews with authors. The other day

it was Mrs Humphrey Ward. Then I was invited to sit, and in the

course of conversation I happened to mention your name, and to say that

I knew you personally. When Mr Dawson, the Interviewer, said how

glad he would be if you would favour him with a chat, I wish you could,

not only for the interest we should all take in reading a Sketch of you

and your work, but because Mr Dawson is a young Journalist on the climb

and trying to lay hold where he can in his upward struggle, and because,

as he explained it, it would be ‘a feather in his cap’ if Alfred Russel

Wallace would be kind enough to see him. I don't know where you

are living now, but if at one of the ends of the earth he would seek you

out.

I am, with all good wishes, and with the hope that you are still working

happily and finding life worth living, and with the Kindest remembrances

to Mrs Wallace

yours faithfully

Gerald Massey.[22]

Of his daughters, Evelyn was the only one who

married. This was to John Henry Bruton aged 31, a private

secretary, on 4 August 1897, their only daughter Helena Viola Massey

Bruton being born on 23 July, 1899. Unfortunately their marriage

did not last long, John Bruton dying from intestinal obstruction two

years later.

|

Gerald Massey's married daughter, Evelyn (Bruton)

with daughter Helena (Miss H. Bruton).

|

|

|

|

Redcot, South Norwood Hill. |

Early in 1903 due to a continuing reduction in

his financial circumstances, Massey was forced reluctantly to make a

last move to a smaller semi-detached house not far from Warminster

Road. At ‘Redcot,’ 46 South Norwood Hill, (now number 24), he

settled finally to complete his writing. Using an upstairs

room as a study that overlooked a vista of trees towards the Crystal

Palace, he had a speaking tube fitted to connect with the drawing

room downstairs. Before venturing down during the day, this

room had to be at a temperature of 60 degrees, so as not to

exacerbate his increasingly severe attacks of bronchitis during the

winter months. Compared with the previous two works, his last

book took a long while to complete, due to his frequent

interruptions by illness. Because of the unforeseen expense he

was compelled in 1904 to apply yet again for a Literary Fund grant.

Supported by John Churton Collins and George St Clair, a member of

the Palestine Exploration Society and Society of Authors who had

reviewed his

Book of

the Beginnings favourably in the Modern Review, he

received £150. By July 1906 with his book nearing completion,

he was obliged to consider the costs of publication. The

property that had provided him with a small rental had been sold

some years earlier, and he was left with the annual £100 Civil List

pension as sole source of income. However, with backing from

Dr Albert Churchward and John Tannahill, a previous neighbour from

Warminster Road, the Royal Literary Fund allowed him £100 towards

the publication of his book. Author friend James Milne, editor

of the Bookman and literary editor of the Daily Chronicle

visited him in 1905, and again in early 1907 just as

Ancient Egypt

was being prepared for publication. He saw that Massey was

cheerful and fresh in mind, although frail and weary. In

comparing the writing of poetry with that of prose, Massey said that

he found the writing of verse more exhausting, sometimes spending a

night in getting a stanza, though he wrote very little poetry now.

It was necessary to feel a thing vitally before giving it out in

words. Mentioning his visit to Tennyson whom he had met in

London when Tennyson was in bed with poor health, he remembered his

frank bluntness, almost roughness of his personality which did not

seem to agree with the Italian suavity of his poetry. If he

himself had been a poet of society, he might have been supping with

duchesses instead of living apart and writing books about the

origins of civilisation. He remembered sending a poem at one

time to either the

Morning Herald or Standard which replied that although

they liked the piece very much, they wanted something milder on the

same lines. They did not get their poem as he always refused

to do anything to order. Concerning his earlier Book of the

Beginnings he found a reference to a review [stated to be in the

Dutch Litteraturzeitung] by Richard Pietschmann (1851-1927) a

German scholar and Egyptologist who had written that:

“This book belongs to the most advanced reconstruction

researches, by which it is intended to reduce all language,

religion, and thought to one definite historic origin . . . The

author, however, differs from all similar writers in that he is an

Evolutionist, holding that he who is not, has not begun to think for

lack of a starting point . . . This view, of which modern philology

has not yet dreamed, has not hitherto had any Egyptian researches

brought to bear in its support. This the author saw, and saw also

that not only must one be an Egyptologist, but also an Evolutionist,

and one of the newer theology.”

Replying to a question as to his next work,

Massey gave a cheerful laugh, and quoted a verse:

|

‘Fight on my men!’ Sir Andrew saith,

‘I am hurt a little yet not slain.

I'll but lie down and bleed awhile,

And then I'll up and fight again.’ |

Then, as if speaking to himself, he added, ‘In this life or some

other.’[23] There was a hint of regret that

he had been unable to devote sufficient time to the younger members

of his family:

|

Child after child would say—

‘Ah, when his work is done,

Father will come with us and play.’

'Tis done; but Play-time's gone. |

In the Norwood area Massey was still regarded as

a notable Victorian poet, and just prior to his 79th birthday a

reporter from the

Norwood News went to obtain an interview. As Massey did

not feel well enough at that time, his daughter Christabel supplied

the reporter with a brief history of her father's early life.

Unfortunately Christabel's memory was not always accurate, and the

reporter had to supplement his article from the introduction to

My Lyrical Life. The outcome, apart from some publicity,

was therefore devoid of any anecdotal interest.[24]

The

Daily Mirror also noted that latest period of ill-health

which confined him to bed for several weeks, and mentioned that some

of his friends were attempting to procure him a grant from the Royal

Bounty Fund.[25]

Ancient Egypt. The Light of the World. A work

of reclamation and restitution in twelve books was published on

the 30 September 1907, financed in part with his grant from the

Literary Fund. Even so, he could afford only to have 500

copies printed. Totalling just under a thousand pages, the

‘twelve books’ were subject sections. The Book of the

Beginnings had dealt principally with comparative philology, the

Natural Genesis with typology, and he wrote Ancient Egypt

as being necessarily more fundamental to the two, being based to a

great extent on astronomical mythology and its development through

to the Christian religion. Massey's thesis, as follows, is

primarily Afro-Egyptian in foundation. Postulating that man,

who was continually evolving, had his earliest origins in Africa

around the area of the great lakes, Tanganyika and Victoria, he

considered that there were several migrations via Egypt which

gradually extended to Europe, Asia, Australia and the Americas.

The earliest was of the paleolithic negroid pygmy people, who were

pre-Totemic. At least two further migrations by Nilotic

Negroes followed, who were Totemic, believed in a Great Mother and

propitiated elementary (superhuman) powers and ancestral spirits.

|

|

Gerald

Massey in his study at Redcot. The last year.

From Book Monthly, 4, 1907.

(The British Library) |

Three other main migrations followed, which could

be determined by the type of myth they had developed up to that

time.[26] At the beginning when the

earliest myths were shaped in the equatorial region, when heaven

rested on the earth, there was equal division of night and day, thus

making the first division of a circle. This tradition was

maintained in the Egyptian ‘Book of the Dead’ where the twelve hours

of darkness were imaged by twelve gates of the underworld in Amenta.

The pole stars were on the two horizons, with the risings and

settings of the stars being vertical. During northward

migration the heaven of that pole, or tree, would appear to rise up

from the mount of earth, while the southern pole star and

constellations would sink below the south horizon—an astronomical

‘deluge’ or ‘fall from heaven’—the beginning of sign language

constellated in the stars.

Passage of time was reckoned by the precession

and circling of the seven pole stars, represented by the seven souls

of the god Ra, and the seven steps for ascending heaven which the

souls climbed to reach their eternal rest among the never setting

stars.[27] This imagery was maintained in

the book of seven seals in Revelation, the Watchers in the Book of

Enoch, the seven footsteps of Buddha, the seven Stations of the

Cross, etc. The northern heaven, therefore, depicted the

Egyptians' primeval homeland in objective uranographic picture form.

Another example of the duality present in Egyptian representation

was that of the water cow, the mother of earth. Symbolised in

part as a thigh, it was constellated in the northern heavens both as

the place of birth on earth, and rebirth in heaven. It is

important in following Massey's thesis to remember that many of the

Egyptians' earliest representation of forms of power were as

zootypes. Therefore the serpent was later translated in

mythology as a form of renewal, and developed in the eschatology as

eternal life. The jackal was the seer in the dark, and became

the guide of the soul in death. Similarly, the hawk became the

soul of the sun, and later Ra, the divine spirit. Solar-based

mythology developed to denote the subterranean path of the nocturnal

sun. The soul's road to the heaven of eternity was now

through, and not round, the subterranean earth, which now had a

firmament - the celestial water—both above and below it. One

pillar supported the firmament above the earth, another below.

There was therefore a dual plan, both stellar and solar, upon which

the Egyptian temples were built. The soul travelled through

twelve gates, corresponding to the twelve hours of darkness, from

the gate of glory at sunset with a first weighing and judgement of

the soul in the great hall of Amenta, to the gate of glory at

sunrise. By means of the Milky Way the soul travels by boat,

climbing a ladder of seven steps—figured on earth in the

seven-stepped pyramid of Saqqara—to join another boat for the final

journey to the circumpolar paradise.

The pyramid, as a form of mount by which the soul

ascends to heaven, is represented also by the Great Pyramid, where

the north shaft in the king's chamber showed the way to heaven,

focused on the then pole star Alpha Draconis, and above the

constellation Cassiopeia. The Sphinx is a commemorative and

representative image of the solar god of the ‘double horizon’, or

two equinoxes. Humanly male in front, and female as a lion

behind, it shows the Pharaoh as the lion-image of solar glory.

It is a compound image of the mother earth, and young god whom she

brought forth upon the horizon of the resurrection. Massey

considered that the Sphinx, or an earlier representation built on

the same site, was older than the pyramids.[28]

Identification of Egyptian deities as gods, goddesses and zootypes

that are depicted in the constellations can be made in the Dendera

zodiac which, although drawn by Greeks, are earlier Egyptian in

type.

Identified with the last division of heaven into

twelve parts are the Sumerian legends of the solar Gilgames, the

Greek twelve labours of Hercules, and the voyages of Jason and the

Argonauts. The journey of the soul from human death to eternal

life has many parallels in world mythology, and formed the basis for

development of religious eschatology. All the Egyptian

religious writings are therefore of particular interest during the

Middle Eastern diaspora with its fusion of Greek and Semitic

systems. This is particularly so in the development of

Christianity, with specific regard to the influence of the

Egypto-Gnostics.

Massey considered that the Egyptian ‘Book of the

Dead’, although being the latest development of Egyptian religious

belief and solar based, combined some of the previous modes of

thought illustrated in the earliest pyramid texts and intermediate

coffin texts. It became ultimately the Egyptian book of life,

and the pre-Christian word of God.

There were only a few reviews of his book, which

he did not live to see. Nature, in common with reviews of his

earlier works, dwelt on his philology which they thought

particularly suspect, and suggested, strangely, that he had not read

deeply enough. It considered his statement that mythology was

not to be fathomed to its depth by means of the folk-tales in

Frazer's Golden Bough, did not accord the right of Massey to

criticize Mr Frazer.[29] Massey had

commented in vol. II, p. 672 that “… mythology is not to be fathomed

in or by a folk-tale, and the Golden Bough is but a twig of the

great tree of mythology and sign-language - a twig without its root

… it was hailed as if it had plumbed the depths instead of merely

extending the superficies …” Massey continued, giving examples

of comparisons. In vol. I, p.9 and in his ‘A

Retort’ (Lectures, ‘The Seven

Souls of Man’, 1887), he replies, very abrasively to critical

comments made by William Coleman, Prof. Le Page Renouf and Prof.

A.H. Sayce. He had already presented his theories, which he

had taken a stage earlier in time than Fraser, that in the most

primitive phase mythology is a mode of representing certain

elemental powers by means of living types that were superhuman, like

phenomena in nature. Mythology exhibits a series of types as the

representatives of certain natural forces from which the earliest

gods were evolved. How these were thought and expressed of old

in this language constitute the primary stratus of what is called

‘Mythology’ today. Early man made use of things to express

their thoughts, and those things became symbols, the beginnings of

gesture sign-language by imitation being earlier than words.

Myths were founded upon natural phenomena and remain the register of

the earliest scientific observation. Massey treats mythology

as the mirror of prehistoric sociology (Natural

Genesis, I, xiv and section I). A brief mention in the

New York Times noted his wide knowledge and elaborate

treatment.[30] The review by George St

Clair, for the

Literary Guide, complained yet again about his philological

renderings, particularly on his interpretation of Hebrew proper

names.[31]

Presentiment that his work had been completed

became reality only a few weeks later. On 9 October he

developed pneumonia.

|

Slow step by step, day after day,

I journey on my homeward way;

And darkly dream the Land of Light

Is drawing near, night after night;

Where I shall reach my

Rest at last,

And smile at

all the troubles past … |

Despite the devoted attention of his daughter

Christabel and the aid of Dr Churchward, he succumbed gradually to

exhaustion and died on 29 October. Obituaries in the

Athenæum, Literary Guide,

Daily News,

Times and

Two Worlds all praised his poetry.[32]

The

Literary Guide

made brief favourable note of his subversions of the Christian

faith, and Two Worlds focused on his Spiritualistic

activities. At local level, the Norwood News summarised

his life, and considered that the moral of his life was the power of

genius to triumph over the most adverse circumstances. From

the Town Hall, Croydon, H. Keatley Moore mentioned that when the

library purchased Massey's Ancient Egypt, he autographed the

copy and wrote a verse for them, adding that it was not every

borough that could boast of a living poet amongst its burgesses … [33]

The following week a local resident, A. R. Speake, sent a poem in

praise of Massey:

… O! we would fain not say to thee ‘Farewell,’

It may be that beyond this universe

We yet shall look, dear Poet, on thy face,

And hear the sweetness of thy voice again.[34] |

|

Massey family grave at Southgate Cemetery

(location Grave No. W.164).

The inscription on the headstone reads . . . .

|

THE STAR OF EVE MAY SET BUT HOW IT

SHINES THE STAR OF MORNING NOW

AND SMILES WITH LOOK OF LOVE THAT DRIES

ALL TEARS FROM OUR UPLIFTED EYES. |

|

The funeral, a quiet family affair with about

fifteen people being present, took place in Southgate Cemetery on

the 4 November. Mrs Massey together with her daughters and a

few friends arrived in two carriages, and the coffin with twelve

wreaths was carried straight to the grave where James Milne, at

Christabel's request, gave a brief address prior to the interment.

An epitaph added later by the family referred to Massey as ‘Poet,

Author, Spiritualist, Egyptologist’, and his uncompromising

allegiance to the Spiritualist's view of death by the inscription,

‘Born May 29 1828. Reborn October 29 1907’.[35]

Massey's will, made on 13 October, witnessed by

Dr Churchward and a neighbour, disclosed the extent to which he had

been reduced financially. The Leader reporting his death had

commented:

If the late Gerald Massey had lived in Johnson's time, he would

probably have incurred, as Milton had done, the Doctor's ungenerous

condemnation, by doing what the Doctor himself did—accepting aid

from the state. Few men could claim to have earned their

modest Civil List Pension more thoroughly than Massey … [36]

But the annual Civil List pension ceased with his

death, and his wife and three unmarried daughters, two of whom were

invalids, found that they had £106 0s 1d (in today's value this

would be equivalent to some £6,000) to live on for an indefinite

period. Acting on the advice that had been suggested to them

just prior to their father's death, they applied for a grant from

the Royal Bounty Fund and, in January 1908, were awarded £200 by the

Prime Minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman.[37]

The following March, Christabel made application for assistance to

the Royal Literary Fund. She received strong backing from

James Milne and Claude Montefiore, and sent the committee a copy of

review extracts from a circular issued for one of Massey's lecturing

tours. The Literary Fund responded with a final grant of £100.

Earlier that year, James Robertson of Glasgow; a

Spiritualist friend, had suggested that a subscription fund be

commenced on behalf of Massey's widow and daughters. They were

hardly in a position to refuse. Robertson commenced this in

May by making a personal donation of £10, distributing a printed

circular to friends, and publicising the fund in

Two Worlds.[38]

The subscription was headed by the Bounty Fund grant, and it was

hoped that a sum in excess of £1,000 would be donated in order to

provide the family with a small yearly income. Although the

final total of the subscription has not been traced, it is likely

that the target figure was reached.

Christabel and the family remained in ‘Redcot’

until 1912, when Massey's widow Eva, and daughters Maybyrn, Cecilia

and Evelyn moved to 43 Casewick Road, Norwood. Maybyrn died of

tuberculosis on 22 June, 1919. Due to Eva's increasing

senility, Christabel joined them in 1923 but the family was unable

to cope. Eva was then placed in a nursing home at 129 Tulse

Hill, where she died on 12 March 1924. She was buried in her

husband's grave at Southgate, but is unnamed in epitaph, due

probably to the family's straitened financial circumstances.

Cecilia died of pleurisy on 30 November 1932 at 7 Stodart Road,

Penge, where she had moved with Christabel following Eva's death,

and Christabel died at 214 Anerley Road, Penge, on 24 February 1934

from chronic bronchitis (for an article by her see under Christabel

Massey in the

Miscellanea section).

Massey's last daughter, Evelyn, who was living then with her

daughter Helena at 26 Palace Road, Streatham, died in Weir Hospital,

Balham, on 1 June 1940 of lung cancer. Following the death of

Helena on 26 February 1988, Massey's direct line had come to an end. |

Mayburn Massey. One of Gerald Massey's unmarried daughters

(Miss H. Bruton).

Gerald Massey's married daughter, Evelyn (Bruton)

(Miss H. Bruton).

(see updates in the passage below)

|

Of Massey's (known) siblings - additional

information to the Family Tree diagram:

-

Edwin was the brother whom Massey had referred as “never able to

look after himself.” Following a few years in the army, he

became an itinerant hawker, dying in the Union Workhouse,

Lincoln, on 1 February 1904. His death certificate states

that he was “accidentally killed by being knocked down by Pony

and Cart”. Edwin appears to have had 4 children—Elizabeth,

b 1856, Mary, b. 1862, Joseph, b. 1867, Lydia, b. 1870, none of

whom are believed to have reached adulthood. The last

record of Edwin's wife, Mary, is in the 1901 Census which shows

her an inmate of the Berkhamsted workhouse.

-

Frederick, then 68 years, appears in the 1901 census as a

“Ladies' Hatter”, a job that seems appropriate taking account of

the importance in Tring, during his childhood, of straw plaiting

to the nearby Dunstable and Luton-based straw hat industry.

In 1901 he lived at 2 Draper Street, Newington, London, with his

wife, daughter and two in-laws. Frederick died of

pneumonia in Forest Hill, London on 10 November, 1910. He

had 10 children including 4 sons—Frederick William, b. 1859 (he

set up the cab drivers' union in South London), Henry, b. 1861,

Thomas Jerrold, b. 1864, and Percy, b. 1882 (died in infancy).

-

Henry Massey is recorded in the 1861 Census as an “Author in

Prose”, but no publications have been traced. At that time

he was staying with the Massey family in Rickmansworth, but does

not appear to have been resident in that locality. Henry

died of pulmonary tuberculosis in Marylebone, London, on 12

July, 1875, the occupation entered on his death certificate

being a "painter's labourer". He appears to have had 3

children — William, b.1867, Percy, b.1872 and Bertha, b.

1873.

Of Massey's other known relatives of the time,

the 1861 census shows Elizabeth Massey, a niece then aged six

(Edwin's daughter), staying at Tring Wharf with Massey's parents.

Born in Sydenham, no registration has been traced. Another

niece, Adelaide Massey (Frederick's daughter), aged 39 and described

as an “Assistant High School Mistress”, is listed in the 1891 Census

staying with the Massey family in London. |

|

|

|

|

Photo, thought to be of Frederick Massey,

one of Gerald Massey's brothers.

(Photo: Heather Massey.) |

|

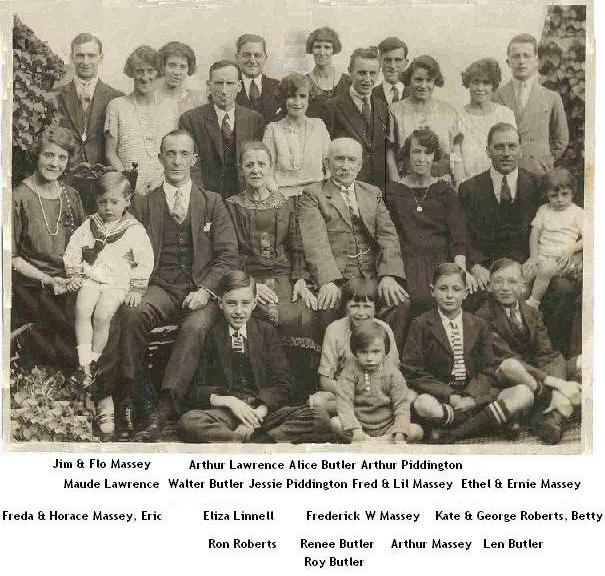

Descendents of Frederick Massey, ca 1927.

(Photo: Heather Massey.)

|

There is no major holding of Massey's correspondence, which is dispersed

in UK and American libraries. The Location Register of 20th

Century English Literary Mss (British Library, 1988) is incomplete and

the 1995 edition contains no further Massey entries. All other

items of relevance have been sourced and are cited in footnotes.

Two references to Massey are made in areas in which

he had resided. Grove Road, Southgate, has an entrance to the New

Southgate Roundabout named ‘Massey Close’, at the corner of which are

‘Massey Close Flats’. The original houses and Baptist Chapel in

the road have been demolished. The name of Massey is remembered

also in his native town of Tring, where a luxury block of flats in Brook

Street—not far from the Silk Mill in which Massey was employed as a

child—is named Massey House in his honour. From 2005 the Tring and

District Residents' Association commenced funding an annual Lyric Poetry

Competition open to pupils at Tring School. The winner accepts the

‘Gerald Massey Prize for Lyric Poetry’. At his last residence in

Norwood it is hoped that the borough will eventually provide a

commemorative plaque under their Croydon Heritage Plaques Scheme.

A number of Massey's early, more pious poems were

incorporated for use as hymns, including number 47 in the Labour Church

Hymn Book, 313 in Songs of Praise, and three in the Spiritualists Hymn

Book. A slightly altered verse from his poem ‘Today

and Tomorrow’ was used by the Welsh miners' Cambrian Combine Strike

Committee in their manifesto of 1911.[39] In

1915 his poem ‘That Merry, Merry May’

was set to music by Christabel Baxendale (Ricordi & Co.). See also

fn. 39 for further listings of his poems that were

set to music.

No evidence of a Spiritualistic post-mortem

communication has been found, although he did appear some years later in

front of his grand-daughter—in the form of a motto in a Xmas cracker:

|

Warm is the Welcome! 'Tis our

way to grasp,

The hand in love or greeting

Fondly clasp.

Gerald Massey.[40] |

While this would no doubt have appealed to Massey's sense of humour, his

grand-daughter was constrained to comment, ‘How have the mighty fallen!’

Following that, he put in an even more physical appearance as the

subject of a cigarette card.

This was one of a series of personalities issued by

Cousis & Co., Malta in the early 1900's. The picture was part of a

larger one published in England in the late 1890's.

[Chapter 9]

NOTES

|

|

1. |

Medium and Daybreak,

17 Jun. 1887, 377-8. |

|

2. |

Ibid. 22 Jun. 1887, 454-5. |

|

3. |

The

Great Cryptogram: Francis Bacon's cipher in the so-called

Shakespeare plays by Ignatius Donnelly, 2 vols. (London, Sampson

Low, 1888). In support of the cypher theory in the plays, see also

E. Johnson's Shakespearean Acrostics (London, Cornish, 1942).

Against the theory, see W. and E. Friedman's The Shakespearean

Cyphers Examined (Cambridge, U.P., 1957).

So far (at least) as the Sonnets are concerned,

Massey was unequivocal in “Admitting

as we all do that Shakspeare wrote his Sonnets …”

Delia Bacon's (unsigned) article, William

Shakespeare and his Plays; an Inquiry concerning them appeared

in Putnam's Magazine, Vol. VII., January—July, 1856 (pp

1-19). Following publication of her first article, the

magazine received such negative comment and criticism that the

proposed series did not materialize. Delia Bacon later

published her theories that Shakespeare was authored by Sir Francis

Bacon, Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser (receiving some support

from, among others, Ralph Waldo Emerson) in The Philosophy of the

Plays of Shakspere Unfolded (London, Groombridge, 1857).

She died in 1859. The politician William H. Smith also wrote a

book on the theory that Bacon authored Shakespeare. Bacon and

Shakespeare: an Inquiry … (London, Smith, 1857). The

“Oxford" theory of Shakespearean authorship was apparently first

proposed by J. T. Looney in his ‘Shakespeare’ identified in

Edward De Vere, the seventeenth earl of Oxford (New York,

Stokes, 1920). Looney's theories regarding de Vere promoted,

in 1957, the establishment of the ‘Oxford Society’, which has since

gained many supporters.

Scholarly theories continue to be published that

assign differing authorship to Shakespeare's works, either complete

or in part. In his large work on the Sonnets (The Monument:

Shake-Speares Sonnets, Meadow Geese Press, Mass. USA., 2005),

Hank Whittemore identifies the author of the Sonnets as Edward de

Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, whose objective in writing them was to

preserve a record of Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton.

In Whittemore's view, Henry Wriothesley was the unacknowledged son

of Edward de Vere and Elizabeth I, and thus had the right to be King

Henry IX of England, a claim that would have been treasonable unless

concealed within the historical parts of the Sonnets.

Whittemore identifies the “Fair Youth” as Southampton and the “Dark

Lady” as Elizabeth I (whereas Massey identifies Lady Penelope Rich,

sister of the Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, as the Dark Lady).

The authors of The Truth Will Out. Unmasking

the Real Shakespeare

(Brenda James and William Rubenstein, Longman, 2005) claim a new

contender, Sir Henry Neville, wrote Shakespeare's works. They

assert also that Neville addressed the ‘Dedication to the Sonnets’

to Southampton, identifying him as the ‘Mr. W.H.’, the mysterious

dedicatee of the work, and that ‘Mr. W.H.’ was Neville's

affectionate nickname for Southampton.

To Shakespeareans, all scholarly theories on

authorship have their own validity and, as such, are worthy of some

attention rather than outright dismissal. While such theories

continue to cast some doubt on the subject, until positive

supporting primary material is discovered they remain a matter of

interesting speculation. |

|

4. |

Punch, 95, (10 Nov. 1888), 221. Donnelly did not wilt too

much. In 1899 he published The Cipher in the Plays and on

the Tombstone [of Shakespeare] (London, Low). |

|

5. |

St.

James' Gazette, 7 Jan. 1889, 7. |

|

6. |

Quoted

in Medium and Daybreak, 5 Feb. 1892, 91. |

|

7. |

Times Literary Supplement, 30 Oct. 1937, 803. Massey's remarks

are on p.420 and in fn. 163

of his

Shakspeare's Sonnets. |

|

8. |

National Review, 12 Oct. 1888, 238-59. |

|

9a. |

See the

Daily Chronicle, 28 May 1888, 5, and 18 Sep. 1888, 3. |

|

9b. |

(i)

W.H. Cundy was a printer and publisher in Washington Street, Boston.

During Massey's first American tour, Massey was hosted at a meeting

of the Franklin Typographical Association in 1874. Cundy was then

president of the society. (ii) The reference to which Massey refers

is not clear. His 10 lectures had been published privately in 1887.

(iii) The Shakspeare book to which he refers would be his Secret

Drama of Shakspeare's Sonnets, 1888. |

|

10. |

Cited

in Banner of Light, 17 Nov. 1888. Lecture report in the issue

of 24 Nov. |

|

11. |

Banner of Light,

15 Dec. 1888, 4. H.P. Blavatsky's journal

Lucifer,

1888, vol. III, 74-78 under 'Gerald Massey in America' gives the

titles of these lectures. |

|

12. |

Athenæum, 9 Nov. 1889, 629-30. |

|

13. |

Saturday Review, 31 Aug. 1889, 245-6. |

|

14. |

Medium and Daybreak, 17 Apr. 1891, 247, and 24 Apr. 264. |

|

15. |

Ibid.

10 Nov. 1893, 709-10. |

|

16. |

Thomas

Lake Harris' Hymns of Spiritual Devotion (New York, 1857)

referenced in Massey's Concerning Spiritualism, 20-21. |

|

17. |

Memoirs of a Social Atom, op. cit., 1, 161-2. |

|

|

18. |

The

Harney Papers, letter 214. Massey's inscribed copy of

My Lyrical Life that

he sent to Harney is in Vanderbilt University Library. |

|

19. |

Harney's biography is excellently presented by A. R. Schoyen in

The Chartist Challenge (London, Heinemann, 1958). John Saville's

introduction to the reprint of Harney's Red Republican and Friend

of the People 2 vols. (London, Merlin, 1966) also has much

information. |

|

20. |

The

Bookman, Nov. 1897, 33-36. |

|

21. |

Ibid.

Jan. 1898, 121-24. |

|

22. |

British

Library Add. Mss. 4644 1.f. 154. |

|

23. |

Book

Monthly, 2, (Jul. 1905), 703-6. 4, (Sep. 1907), 845-51.

(Referred to also, and expanded in an article by W. H.Simpson in

Two Worlds, 7 May 1906.) |

|

24. |

Norwood News, 25 May 1907, 5. |

|

25. |

Daily Mirror, 21 May 1907, 4. |

|

26. |

See

Churchward, Signs and Symbols of Primordial Man (op. cit.)

437, for a chart of these proposed migrations. See also his

Origin and Evolution of the Human Race (1921). He closely

follows, and summarises Massey. |

|

27. |

Massey

used the (then) up-to-date information in Sir J. Norman Lockyer's

Dawn of Astronomy (London, Cassell, 1894), the first book to

demonstrate an astronomical basis in Egyptian temples. Massey

reprinted the diagram on p. 127 showing the precession of the

equinoxes. In a letter to Lockyer dated 30 June 1906 written by his

daughter Christabel and signed by him, he requested permission to

publish that and two other diagrams. Ms. Exeter University. |

|

28. |

Ancient Egypt, 1, 336-39. |

|

29. |

Nature, 77 (30 Jan. 1908), 291-2. |

|

30. |

New

York Times, 15 Feb. 1908, 89. |

|

31. |

Literary Guide, 1 Feb. 1908, 21-22. |

|

32. |

Athenæum, 2 Nov. 1907, 553. Literary Guide, 1 Dec.

1907, 183 and 187-8. Daily News, 31 Oct. 1907, 4. Times,

30 Oct. 1907, 8.

Two Worlds,

8 Nov. 1907, 558-9. |

|

33. |

Norwood News, 2 Nov. 1907, 8. |

|

34. |

Ibid.

9 Nov. 1907, 3. |

|

35. |

Grave

No. W.164. The grave was initially prepared and used for Massey's

daughter, Hesper, as the main headstone depicts. See

photo. |

|

36. |

The

Leader; 30 Oct. 1907, 3. |

|

37. |

Acknowledgement in British Library Add. Mss. 412401.215. |

|

38. |

Two Worlds, 8

May, 1908, 23 1. |

|

39. |

Benn,

Tony, (ed.) Writings on the Wall. A Radical and Socialist

Anthology 1215-1984 (London, Faber, 1984), 157. The poem was

used in the context of a manifesto by the South Wales miners, 16

June 1911, in their minimum wage dispute. Further poems of Massey's

that have been set to music are held at the following Libraries (see

also 'Sheet Music' under

Miscellanea):

• No Jewelled Beauty is my Love, poetry by Gerald Massey.

This is a single copy of 'In Happy Moments' ballad, from W. Vincent

Wallace's Grand Opera Maritana performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury

Lane, and dated 1845. The original words by Edward Fitzball have

been covered in manuscript by part of the first two verses of

Massey's 'No Jewelled Beauty is my Love.' The top of the score

carries the citation: 'The Poetry of this Ballad is by Gerald Massey

Esq.r'. This copy of the Ballad was obtained by the British Library

in 1873, and the origin and date of the copy is not known. British

Library Shelfmark H 1654.q.(14). Photocopy in The Gerald Massey

Collection, Upper Norwood Joint Library.

• Before Sebastopol, poetry by Gerald Massey, music by Joseph

Frederick Leeson. Published by J. Purdie, Edinburgh; Chappell,

London, c. 1855. (British Library).

• Desolate, music by Flora, published by Chappell & Co,

London, 1875 (Cambridge University Library).

• A Maiden's Song, music by William Shepherd, published by

Weekes & Co, London, 1877 (Cambridge University Library).

• O! Clasp thy hands little one, music by Beta, published by

Metzler & Co, London 1877 (Cambridge University Library).

• That merry, merry, May, music by Charles W. Thomas,

published by Novello, Ewer & Co, 1878 (Cambridge University

Library).

• The People's Advent: a new Quartette for the Times. Words

by Gerald Massy [sic]; music by James G. Clark. (1830-1897).

Published by H.M. Higgins, Chicago c. 1864. (Rare Books & Special

Collections Division, Library of Congress). Copy available in the

Gerald Massey Collection, Upper Norwood Joint Library.

• Together. Song for Medium Voice. Words by Gerald Massey,

music by J.A. Parks, published by J.A. Parks Co, York, Nebraska.

(Kilgore Memorial Library, York, Nebraska.)

• Down in Australia. Two-part song. Words by Gerald Massey,

music by Clara Angela Macirone. Published by J. Curwen & Sons,

London, 1903 (British Library). |

|

40. |

From

the first verse of his poem 'The

Welcome Home.' |

|