|

JOHN ARNOTT

(1799 – 1868)

GENERAL SECRETARY,

NATIONAL CHARTER ASSOCIATION

by David Shaw.

|

――――♦――――

JOHN JAMES BEZER, CHARTIST

AND JOHN ARNOTT,

NATIONAL CHARTER ASSOCIATION

BY

DAVID SHAW

now on sale at

LuLu.

――――♦――――

|

Little information is available concerning

the personal life of John Arnott, who was noted for being sometime

Secretary and General Secretary of the National Charter Association.

His name comes down to us principally in the reports of meetings of the

National Charter Association, and other associated organisations with

which he was involved during a period from the mid 1840’s to mid 1850’s.

Details of the particular events together with their background can

readily be traced in the relevant Chartist newspapers and books on

Chartist history.

It is probably safe to

infer that John Arnott joined the National Charter Association soon

after its inception in 1840. His progress within the organisation

was rapid, and he was highly regarded and respected for his efficiency.

However, there is no record of him undertaking lecturing or article

writing that would have brought his name to a more prominent position in

the Chartist press, although he did compose some poems that were

published in the Northern Star. From 1853 and the virtual

death of the Chartist movement, he is unrecorded. It appears that

he, together with many other official stalwarts gave up that particular

struggle, and supported associated organisations, or continued with

their own personal affairs.

John Arnott was born on

the 22 October 1799, at Chesham, Bucks, the son of William and Mary

Arnott. There were another three sons and two daughters in the

family, all born in Chesham, between 1802 and 1807. George, born

29 April 1802; Elizabeth, born 1 December 1804; Joseph and Benjamin

(twins) born September 1807.

On the 19 October 1819,

he married Sarah Allen at Chesham Bois. It appears that he resided

in Chesham until 1830 – 1835, when the family moved to London.

Census records for 1841

show him residing at Suters Buildings, St Pancras, with his wife and six

children – Alfred 15, b. Chesham; Ann 13, b. Chesham;

Benjamin 11, b. Chesham; Emma 4, Sarah 2, and Edwin 4 months b. St

Pancras. John Arnott is listed there as a ‘Cordwainer’

[Shoemaker]. Suters Buildings appear to have been situated in

Somers Town in an area between Ossulston Street, Middlesex Street,

Phoenix Street and Chapel Street. Today, now redeveloped, between

Ossulston Street and Brill Place, behind the British Library.

Arnott obviously made

steady progress within the National Charter Association. In 1844,

he was a member of the Somers Town Branch of the Metropolitan Delegate

Council. On the 8 June (Northern Star) at a meeting of the

Council he moved that a national petition be got up by each locality

praying for the deliveration of

Thomas Cooper, now confined in Stafford

Gaol. On the 3 August, he took the Chair at a Delegate Council

meeting, and on October 5 at a Council meeting, he was elected

Secretary. His address at that time was given as Middlesex Place,

Somers Town.

On December 10 1844, a

well attended soiree was held at the Literary Institute, John Street, in

honour of the removal of the Northern Star from Leeds to London.

Harney, O’Connor and other leaders were present, and gave many toasts

and strong addresses. John Arnott sang a patriotic song amidst

considerable applause. On January 18 1845, he was elected

Secretary of the Delegate Council with re-election on the 13 May for a

further three months.

On the 19 March his

eldest son, Alfred, at 8c Middlesex Place, Somers Town, married Eliza

Cavell of the same address. Eliza’s father listed as a labourer.

The next year, 1846,

was a year of great cheer for the Chartists. Feargus O’Connor had

been preparing his Co-operative Land Society for a launch that, he

anticipated, would place the Chartists at the forefront of land

co-operative for impoverished workers. Many of the prominent

Chartists supported the venture, including

Ernest Jones. John Arnott also gave

his support, and provided a poem that he composed especially for the

occasion.

This was an over

optimistic eulogy for the opening celebration of O’Connor’s ill-fated

Society (The National Land Company) to be held on the 17 August 1846.

The People’s First Estate (the first of six purchased and plots issued

by shares) was some 100 acres located at Heronsgate, near Rickmansworth,

and was known as ‘O’Connorville.’ It had 35 specially designed

properties for cheap rent, and a schoolhouse. (See The Chartist Land

Company, A.M. Hadfield, David & Charles 1970, p.101.) The poem

was printed and placed on sale at the site on opening day, priced 1d.

|

Northern Star, August 1

1846, p.3.

Songs for the People xxiv.

The People’s First Estate,

Or, Anticipation of the 17th

August.

Air,—“The days that we went gipsying.”

Come let us leave the murky gloom,

The narrow crowded

street;

The bustle, noise, the smoke and din;

To breathe the air

that’s sweet.

We’ll leave the gorgeous palaces,

To those miscalled great;

To spend a day of pleasure on

The People’s First

Estate!

CHORUS,—

On this estate the

sons of toil

Shall independent

be,

Enjoy the first fruits of the soil,

From tyranny set

free!

The banners waving in the breeze,

The bands shall

cheerfully play,

Let all be mirth and holiday

On this our holiday

Unto the farm—“O’Connorville,”

That late was “Herringsgate,”

We go to take possession of

The People’s First Estate!

On this estate, etc.

When on the farm! The People’s Farm!

This land of liberty!

We’ll join the dances and rural games,

With joy and sportive glee,

Our gambols play, throughout the day,

(To scoffers you may

prate,)

And leave at night this lovely scene,

The People’s First Estate!

On this estate, etc.

May nature shed her choicest stores,

On this delightful

spot;

Each occupant be blest indeed,

And peace attend each cot.

And may our brave Directors with

The funds that we’ll create,

Live long to purchase hundreds more

Like this our first estate!

On our estate the sons of toil

Shall independent be;

Enjoy the first fruits of the soil,

From tyranny set free!

John Arnott

Somers Town

July 27 1846. |

Arnott had

earlier composed a poem for the occasion of the First Annual Festival to

celebrate the anniversary of the French Republic. This was held at

the White Conduit Tavern on April 21 1846, but the poem was not printed

in the

Northern Star until some time later.

|

Northern Star,

19 September 1846, p. 5.

Songs for the People no. xxx

A SONG ADDRESSED TO THE

FRATERNAL DEMOCRATS.

Air—"Auld Lang Syne" |

|

All hail, Fraternal Democrats,

Ye friends of Freedom hail,

Whose noble object is—that base

Despotic power shall fail.

CHORUS

―

That mitres, thrones, misrule and wrong,

Shall from this earth be hurled,

And peace, goodwill, and brotherhood,

Extend throughout the world.

Associated to proclaim

The equal rights of man.

Progression's army! firm, resolved,

On! forward lead the van.

Till mitres, thrones, misrule and wrong,

Shall from this earth be hurled.

And peace, goodwill, and brotherhood,

Extend throughout the world.

To aid this cause we here behold,

British and French agree,

Spaniard and German, Swiss and Pole,

With joy the day would see.

When mitres, thrones, misrule, and wrong,

Will from this earth be hurled,

And peace, goodwill, and brotherhood,

Extend throughout the world.

We now are met to celebrate

The deeds of spirits brave,

Who struggled, fought, and bled, and died,

Their misrul'd land to save.

For mitres, thrones, misrule and wrong,

From France they nobly hurled,

And would have spread Democracy

Throughout this sea-girt world.

Though kings and priests might then combine

To crush sweet liberty,

We tell them now that they must bow,

That man shall yet be free.

That mitres, thrones, misrule and wrong,

Shall from this earth be hurled,

And peace, goodwill, and brotherhood,

Extend throughout the world.

Oh! may that period soon arrive,

When kings will cease to be,

And freedom and equality

Extend from sea to sea.

Then mitres, thrones, misrule and wrong,

Will from this earth be hurled,

And peace, goodwill, and brotherhood,

Shall reign throughout the world. |

John Arnott

Somers Town, September 1846 |

The poem was followed by a similar stirring piece by George Julian

Harney, titled ‘All Men are Brethren’. A song for the Fraternal

Democrats.

Appreciative, as many were, of the hard work and dedication showed by

Ernest Jones, Arnott then composed a poem in his honour, in the form of

an acrostic:

|

Northern Star

17 October 1846, p.3.

An Acrostic.

To Ernest Jones, Esq., Barrister-at-Law

Estranged Aristocrat! What leave the favoured few,

Regardless of fortune and prospects in view,

(Noble Democrat) to join the

Chartist band,

Eschewed, despised, and

scouted through the land.

Such conduct we esteem, nay

more, admire,

Thy spirit burns with

freedom’s sacred fire.

Just as the trav’ler

pursuing his lonely way,

On whose dark path meteors

bursting play,

Now changing gloom to bright

refulgent day;

Ernest we hail thee, from

thy genius bright

Shines in full power pure

Democratic light.

John Arnott

Somers Town.

Oct. 12th

1846.

|

[Note: The first letter of each

line forms the name ‘Ernest Jones’.]

The following year Arnott composed yet another poem to honour Thomas

Slingsby Duncombe (1796—1861) MP for Finsbury, who had petitioned for

the release of imprisoned Chartists in 1842. Duncombe was also

sympathetic towards Louis Kossuth and Guiseppe Mazzini. Mazzini,

exiled in England, had the aim of promoting Italian unity, republicanism

and democracy. He was suspected by the government of being a

participant in organising an attempt at an invasion of Italy, and Sir

James Graham, Home Secretary authorised the opening of Mazzini’s

letters.

|

Northern Star, March 13 1847,

p.3.

A SONG

(Air – with Helmet on his Brow)

In

honour of that indomitable friend and advocate of the

Rights

of Labour,

T.S. Duncombe, MP.

Let the base sycophant

Of wars and

heroes sing;

‘Laud the despot’ cringe and bow

To Emperor or King:

I scorn such fulsome themes,

I sing of the patriot brave,

Duncombe, the friend of Liberty,

And Labour’s worn-down slave.

CHORUS—

Let all as one smite,

And join in freedom’s cause,

Shouting for

“Duncombe and our Right;

Free, just, and equal laws!”

When the Whigs and Tories join’d

The

Labourer to enslave,

Duncombe crush’d their monster Bill,

And consigned it to its grave.

The Post-office espionage

Pursued in Graham’s plan,

Duncombe did nobly upset,

And exposed that hateful man.

Let all as one, etc.

The poor in Bastilles doomed

Their wretched lives to spend,—

The toiling slaves—the factory

child—

Duncombe has been their friend;

He has their wrongs denounced,

He will

their rights demand,

And labour would emancipate

From the grasping tyrant hand.

Let all as one, etc.

He will defend the oppressed,

The Irish or the Pole;

The deeds of despots are deplor’d

By his patriotic soul.

Duncombe they cannot bribe—

He’s honest firm and bold,

And, as the leader of our cause,

His worth cannot be told.

Let all as one, etc.

Let the Tories talk of Peel,

The Whigs of Russell boast,

Duncombe is our champion,

And this shall be our toast:—

“To Duncombe and the Trades,

Duncombe and Liberty;

To Duncombe and the Charter,

And may we soon be free!”

Let all as one smite,

And join in freedom’s cause,

Shouting for “Duncombe and our Right;

Free, just, and equal laws!”

|

|

John Arnott. Somers

Town. |

Until

the virtual demise of the National Charter Association, the ensuing

years were busy for John Arnott. In August 1846 he had taken the

Chair at the first Amalgamated Meeting of the chartist’s Veterans,

Orphans and Victim Relief Committee, and at a public meeting in

October at St Pancras on ‘The Charter and no surrender’, he read and

moved the adoption of the National Petition. In the same month he

was elected a member of the Fraternal Democrats, and referred to at that

time as the ‘Somers Town Chartist Rhymer.’ In October he was

appointed Assistant Secretary to the Veterans, Orphans and Victim

Committee, and in November at the South London Chartist Hall, he was

Sub-Secretary. In the following month his poetry was again noted,

and he was mentioned then as “our respected and indefatigable

sub-secretary, Rhyming John Arnott.” His address was given as 8

Middlesex Street, Somers Town.

Considerable prominence was being given in the following year to the

Chartist petition that was to be presented to Parliament in April 1847.

This publicity caused fears of violence, and a pseudonymous letter was

published in the Times of 1 April in which the writer quoted an

announcement by ‘Vernon’ made at a recent Chartist meeting. In

this, mention was made of an intended procession of between 100,000 to

300,000 persons. The writer of the letter queried protection of

the rights of shopkeepers against the ‘tumultuous proceedings,’ and that

suspension of their business appeared to be an infliction and a robbery.

This letter was brought to the attention of the Chartist Committee

appointed to deal with the arrangements of the demonstration on the 10

April. John Arnott, as Secretary, was requested to repudiate in

the strongest terms the language thus ascribed to have been uttered by

Mr Vernon, and to state most emphatically that it was the “firm

determination of the committee that the demonstration shall be

peaceable, orderly, and moral display of the unenfranchised toiling

masses.” (Times, 4 April 1848) Arnott’s address was given

as 11 Middlesex Place, Somers Town.

During January and February 1849 Arnott was

Secretary of the National Victims Fund, also on the Central Regulations

and Election Committee, as well as the Committee of the Fraternal

Democrats. On the 3 March, a Public Meeting was held at the John

Street Institute on ‘The Separation of Church and State.’ A

petition was drawn that the Industrial classes are impoverished due to

evil legislation, and have to contribute to the support of a National

Church—known only to petitioners as a tax-collector. Religion does

not need the assistance of the State. The petition, proposed by

Arnott and another member, was to be forwarded to the MP for Tower

Hamlets, but nothing positive came of it.

On the 24 March, Arnott, on behalf of he National Victim and Defence

Committee (assumed to be the Relief Committee as previously mentioned)

made a request for more financial contributions. He noted that the

law made widows and nearly 100 orphans plus the wives and families of

Ernest Jones, Peter McDouall and others dependent on support.

Giving 3 shillings each to the widows and one shilling for every child

under 12, left the Committee liabilities of £10 p.w. That week,

two shillings only could be afforded to a woman with 5, 6, or 7 children

for seven days.

In August, it was reported that the balance sheet over 17 weeks showed

receipts as £103, expenditure £102. This amount was divided

amongst 31 families (30 grown persons and 70 children), and Arnott made

a further appeal the following month.

London branches of the NCA met on a regular basis to discuss general and

local issues—and it appears that some of the proposals were destined

only to give verbal support to the overall cause. On the 31 March

1849 Arnott seconded a Resolution ‘that the present so-called

representation of the people is a monstrous injustice on the nation at

large, and a violation of the British Constitution.’ About this

time, it was realised that it would be an advantage if local groups

could cohese and provide general unity within the movement. At a

meeting of the General Registration and Election Committee, Arnott and

another member proposed that a Hand-Book and Guide to Regulations and

Elections be published at two pence a copy, and that the Chartist

Executive be requested to aid circulation. The Metropolitan

District Council to consist of two members from each locality within the

metropolis and suburbs, and to cause a fusion of all whom advocate

Chartist Suffrage, into one united phalanx.

July 1850 was the month that Ernest Jones was released from prison.

He was met by John Arnott and several others, and the next day the

Fraternal Democrats gave a supper in his honour. Arnott, G.W.M.

Reynolds, Bronterre O’Brien, George Julian Harney and others proposed

toasts in his honour. Testimonials were presented, together with a

pair of large portraits of Mr and Mrs Jones. The following day,

there was a public meeting at the John Institute in honour of Jones’

release. Harney took the Chair, with the Executive of the NCA on

the platform, and Walter Cooper, Reynolds and others gave addresses.

Later that month, the NCA Executive met with a view of reuniting the

NCA, Fraternal Democrats and National Reform League into one body.

The name suggested was the National Charter Association Federal

Union—later agreed to be National Charter and Social Reform Union.

This inevitably received a mixed reception, and caused ongoing dissent.

On the 27 November 1850, the NCA Executive Committee resigned, and votes

were taken for another Executive. The General Secretary was to be

paid, while the Executive were unpaid. Arnott was elected to the

Executive, and later was confirmed as General Secretary, thus replacing

Samuel Kydd who was receiving a salary of £2 per month.

The 1851 census return for 11 Middlesex Place, Somers Town, gives: John

Arnott, 51. Cordwainer, b. Chesham; Sarah Arnott, 51, b. Bovington,

Herts.; Benjamin, 21, Brush finisher; Emma, 14; Sarah, 12;

Edwin, 10.

Arnott’s son, Benjamin, was married on the 13 April 1851 at Trinity

Church, St Andrew to Eleanor Wilmott, of Middlesex Place. Her

father, like Arnott, was also a Shoemaker, and the couple went to live

at 9 Brill Place, Somers Town.

Differences of opinion concerning the best way to promote the Chartist

movement were becoming more acute in that period. At a meeting of

the NCA on the 19 March 1851, Arnott and Ernest Jones proposed a long

stirring address for unity, to be read at locality meetings. The

main drive of the address, similar to one given as at a meeting the

previous year, was to unite disparate organisations in one phalanx.

‘Henceforth let social co-operation go hand in hand with political

organisation . . . Unite! unite! unite! The convention must be the

PARLIAMENT OF LABOUR! The Executive, the MINISTRY OF THE

UNENFRANCHISED!’

Some of the Districts were also becoming opposed to the leaders of the

National Charter Association, with John Arnott also subject to

displeasure. In the

Northern Star of 22 March 1851, Arnott responded via the Editor to

criticisms made by the Radford locality in a postscript item in the

previous issue. He replied:

“. . . the postscript

runs thus—‘We have frequently seen notices from the Executive, stating

that correspondence had been received from Radford and other places

complaining of their inability to send delegates. So far as we are

concerned, we deny such a statement.’

Now, Sir,

being of opinion that the above is calculated to damage the Executive,

and to impress the idea on the public mind that I, as their secretary,

have published FALSE REPORTS, I, therefore, feel it to be my duty, in

reply thereto, to state that I have minutely examined the printed

reports for the last eight weeks, and I must say that Mr. Brown has

superior penetration to what I possess, as I cannot find Radford therein

mentioned, consequently, I request Mr. Brown to point to the reports to

which he alludes, and, failing doing so, I shall leave it for our

readers to decide which has published a false statement, Mr. Brown or

myself...’

In

another instance, it had been agreed earlier that the Metropolitan

Delegate Committee’s meetings would include representatives from the NCA

Executive. For some reason, these did not turn up a meeting held

in December. A report in the

Northern Star for 20 December 1851 concerning the election of a new

NCA Executive expressed the displeasure of one locality:

Finsbury

Locality. Report from the Metropolitan Delegate Committee: “That

this locality consider the absence of the whole of the Executive from

the Metropolitan Delegate Committee meeting as deserving of explanation;

and the General Secretary is deserving of censure, seeing that it was

his duty to have attended the aforesaid meeting. The locality

recommend the new Executive to elect as their General Secretary a man of

known ability and straightforward conduct and able to address Public

Meetings, and that we recommend Thomas Martin Wheeler— seeing that the

inefficiency of the late General Secretary is a matter of public

notoriety and regret.”

It appears

that Arnott, who had family responsibilities and relied for his living

as a shoemaker, acted principally as an administrator and could not

afford the time to lecture, even locally. Lecture tours demanded a

considerable amount of time away, with some expenses not always

reimbursed. Arnott was therefore considered a less active

participant than Thomas Wheeler. However, neither the NCA nor

Arnott appeared to have responded to the remarks made by the locality.

In early January 1852, the new Executive Committee had their first

meeting, during which dissentions became even more apparent.

Harney had declined to stand for election, believing that the NCA was

virtually finished. Arnott was present, with

John James Bezer in the Chair. Arnott read a letter from

W.J. Linton, in which he stated his

belief that it was impossible to resuscitate the Chartist movement, and

declined to sit on the Executive unless the movement joined the middle

class. Ernest Jones resigned. The NCA had for some time

developed a strong socialist stance, attempting to unite the Chartists,

the Co-operatives and the Trades into one movement. The Manchester

Chartist’s supporters opposed the NCA. Arnott then read the

accounts, revealing a debt of some £37. Unable to pay the

Secretary’s expenses, it was moved that J.M. Wheeler act as Secretary,

but this was not seconded and Wheeler resigned from the Committee.

John Arnott then agreed to serve for one month, but two members opposed

the nomination, and the Chairman’s vote caused his resignation as

Secretary, although he remained on the Committee. Other members

were nominated, but declined to stand. Finally, James Grassby

consented to act as Secretary for one month.

In one of a series of articles in the Northern Star, on January

17 1852, a pseudonymous ‘Censor’, complained that “... the charge of the

people’s cause has fallen into the hands of Messrs Arnott, Bezer,

Grassby, Shaw and

Holyoake...” and asked “if these are

the persons who should be entrusted with the conduct of so important a

movement ... knowing how limited were the powers which such persons

could bring to the duties they aspired to discharge...”

In broad terms the accusation was correct, as the Executive were ruled

by dissention, opposition, and decreasing support from the working

classes. Harney had wanted a merger between Chartists, trades

unions and co-operatives, whilst Ernest Jones continued to press for the

NCA as the sole Chartist organisation. This barely viable NCA

lasted until 1858 when it finally ceased to exist.

The apparent inefficiency of the Executive of the NCA was now blamed for

the miserable state of the Chartist movement, and Arnott and the

Executive complained that the Manchester Council was set up to supersede

the NCA. Another meeting referred to the Finsbury Locality having

objected to Messrs Le Blond and Thornton Hunt having seats (replacing

Linton and Jones). James Grassby in response stated that, “We

think it a pity that men seeking political power should have such a

vague knowledge of how to use it.”

On the 27 March 1852

The Star and National Trades’ Journal reported a meeting of the

Executive Committee, when the famous statement was made that it was “The

Executive of a society, almost without members, and without means –

members reduced by unwise antagonism without, and influence reduced by

repeated resignations within...”. Despite this, it was later

agreed that Arnott and Bezer and others were to continue in office

(probably only on a temporary basis for three months), and Arnott

remained on the Democratic Refugee Committee up to November 1852.

The situation was similar to that of William Lovett’s earlier Working

Men’s Association that had, in October 1836, proposed resolutions

towards a viable ‘People’s Charter’. Thomas Cooper, Feargus

O’Connor and George Julian Harney were members for a time, including a

number of well known later Chartist activists. In 1849 that

Association was in debt, and it was stated that “Cliqueism and

dissentions helped to kill that Association, as in other movements.”

(A History of the Working Men’s Association from 1836 to 1850, by

George Howell, 1900. Published Frank Graham, Newcastle, 1970).

In July 1853 the American and British public were stirred by the news

regarding the rescue of Martin Coszta, a Hungarian refugee from an

Austrian ship in the port of Smyrna. Coszta was residing in

America, and visiting in Smyrna on business. He had stated that he

wished to become an American citizen, but was taken by a party of armed

Greeks employed by the Austrian consul general, and held on their ship.

Captain Duncan Ingraham, commanding a 22 gun sloop-of-war, received

permission from the US charge d'affairs in Constantinople to request

Coszta's release, or use force to obtain it. This was despite

Hungarian ships in the harbour, with firepower greater than Ingraham’s.

It was then agreed that that Coszta be released to the French consul and

from there returned to the United States.

In England, an

Ingraham

Testimonial Fund Committee

was formed, with Arnott as Secretary. The Chairman was G.W.M.

Reynolds, with other members that included George Julian Harney, James

Grassby, Samuel Kydd, Walter Cooper and Robert Le Blond as Treasurer.

Ingraham was presented with a medal from the US president for

Vindicating American Honour, and following the subscription, an

inscribed chronometer from the working classes of England.

The 1861 census return for Arnott’s last stated address, 11 Middlesex

Place, shows it as unoccupied. At the same time, his second eldest

son, Benjamin, 30, was residing at 47 Middlesex Street as a ‘Licensed

Hawker’. His wife, Eleanor, 33, was a laundress, with children

Eleanor Diana, 9; Elizabeth Mary, 3; and Clara, 7 months.

John Hollingshead in his Ragged London 1861

(Smith, Elder), mentions Somers Town as being full of courts and alleys,

cheap china shops, cheap clothiers and cheap haberdashers.

Wherever there is a butcher’s shop, it contrives to look like a

cat’s-meat warehouse. Its side streets have a smoky, worn-out

appearance. Every street door is open, no house is without patched

windows and every passage teeming with children. It had a

population of some 35,000, and was more industrial than the adjoining

Agar Town, between Euston and Kings Cross stations, that was referred to

as a disgrace. The Midland Railway cleared Agar Town and part of

Somers Town in 1866.

Thomas Martin Wheeler (b. 1811), was a valued Chartist member, author

and lecturer. A strong supporter of Feargus O’Connor and his Land

Plan, he had purchased a plot at O’Connorville, where he resided for

some time. He was elected to the NCA Executive in 1841, and became

a popular General Secretary from 1842 to 1846. He died in 1862 and

was buried at Highgate Cemetery. Twenty-four horse-drawn carriages

followed the hearse to Highgate, accompanied by a large procession.

John Arnott, who had supported Wheeler’s aims, also attended the

funeral.

According to

W. E. Adams

in his Memoirs of a Social Atom,

chapter xvi, “Some time about 1865 I was standing at the shop door of a

Radical bookseller in the Strand. A poor half-starved old man came

to the bookseller, according to custom, to beg or borrow a few coppers.

It was John Arnott! Chartism was then, as it really had been

for a long time before, a matter of history.”

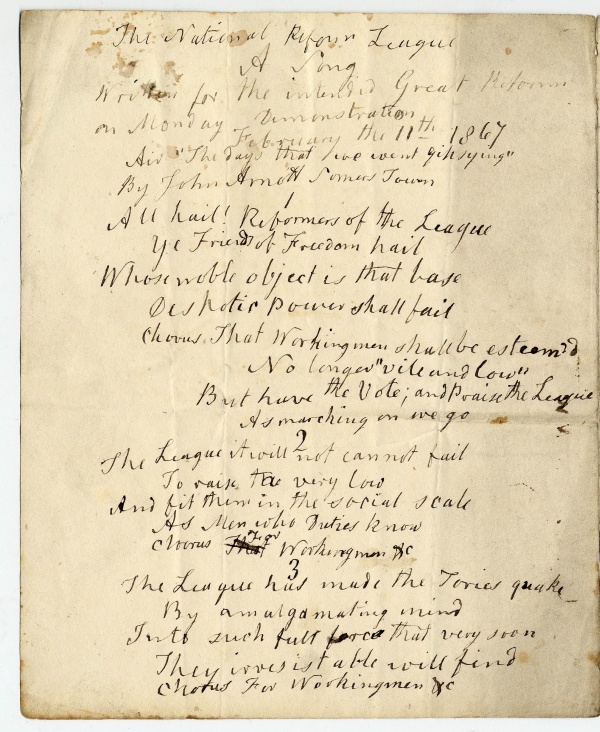

Some time after this, probably in 1866, Arnott suffered a stroke.

However, he was able to compose a poem that he sent to Edmund Beales

(1803-1881) Chairman of the Reform League, for their forthcoming meeting

at the Agricultural Hall, Islington, on 11 February 1867. As a

chartist Arnott had of course supported those activities promoting

manhood suffrage and the ballot, and he continued now by the only means

available to him - through a poem:

|

The National Reform League,

A Song.

Written for the intended Great Reform

on Monday Demonstration,

February the 11th 1867.

Air "The days that we went gipsying."

By John Arnott, Somers Town.

-1-

All hail! Reformers of the League,

Ye Friends of Freedom hail,

Whose noble object is that base

Despotic power shall fail

Chorus:

That Working men shall

be esteem'd,

No longer "vile and low,"

But have the Vote; and

Praise the League

As marching on we go.

-2-

The League it will not can not fail

To raise the very low,

And fit them in the social scale

As Men who duties know.

Chorus: For Working men etc.

-3-

The League has made the Tories quake

By amalgamating mind

Into such full force that very soon

They irresistable will find

Chorus: For Workingmen etc.

-4-

Ye "thousands of" The Reform League,

Concentrate all your Powers,

Your foes are strong your cause is just

(The front of battle cowers);

Be firm United one and all,

The Prize is Liberty,

Tell the Tories now that they must bow

That Men will soon be Free.

Chorus: For Working men etc.

-5-

So sure as winds the billows dash

Across the foaming Sea,

Orbs still roll on and Natures works

In harmony agree;

So shall this glorious cause Progress

It can not will not fail,

And with such Champions as Beale and Bright,

It must it shall prevail.

Chorus: For Working men etc.

John Arnott

(a Poor Paralysed old Chartist)

1 Equity

Buildings

Somers Town N.W.

Janry 16th 1867 *

|

* (Acknowledgements to

Bishopsgate Library, Bishopsgate Foundation and Institute. Ref:

Howell/11/2D/131).

The meeting in Islington commenced with a march from

Trafalgar Square, and was represented by a countrywide number of Trade

Union and Reform League Branches carrying banners and accompanied by

brass bands. The Times of February 12, p.12 reported that

there were no fewer than 30,000 - 60,000 persons in attendance.

During the meeting a group called 'The Reform League Minstrels' chanted

verses that had been printed, and were then distributed at a penny each,

but there is no record of Arnott's poem being made available at the

meeting.

On 28 April 1868, John Arnott was admitted to St

Pancras Workhouse probably from his and his wife’s residence, at Equity

Buildings, Somers Town. He died shortly afterwards on the 6 May of

‘Paralysis’ [a term for a stroke, at that time], aged 69. His

occupation was given as Shoemaker Journeyman.

St Pancras Workhouse held between 1,500 and 1,900 inmates, of which 200

occupied sick wards, 60–70 were lunatics and idiots, and about 1,000

were helpless infirm and aged. (Illustrated London News, 3

October, 1857).

John Arnott was buried on the 12 May in St Pancras Cemetery, High Road,

East Finchley, grave no 47, section 10J. The grave was a

‘communal’ (pauper’s) grave, and there is no headstone.

Reports of his activities from the Northern Star show that

throughout his ten years with the National Charter Association and

other associated organisations, he was well liked and respected for his

impartiality.

This was a sad ending for one of the Chartists’ relatively

undistinguished but ardent supporters who had reached the peak of

the Chartist Administration.

Two years after John Arnott’s death, his wife, Sarah Arnott, died on the

17 February 1870 age 71 of ‘Senile Decay’. She was still

living at 1, Equity Buildings, Somers Town. The informant—who made

her mark—was Eleanor Arnott, daughter-in-law, (wife of Arnott’s son,

Benjamin) of 41, Middlesex Street, Somers Town.

In his tour of the area, Charles Booth in 1898 wrote of Equity Buildings

as a queer little paved cul-de-sac; low one storey two-roomed cottages,

with a little wash house and yard behind; been done up during last year;

doors open straight into room; many of the houses appeared to be very

full of furniture; rents from 6/6 to 7/-.

Equity

Buildings are marked on large scale maps of the period. Now

redeveloped, it was between what is now Ossulston Street and Polygon

Road, with the entrance in Phoenix Road. See the 1863 map below:

Of interest to Genealogists, I append details of a few of John Arnott’s

children:

|

1871 census.

No Arnotts listed at 41

Middlesex Street. 21 Middlesex Street, Alfred Arnott, 47, Shoemaker.

Eliza Arnott (wife) 45. Charles, 21, Carman. Eliza, 15, Shop girl.

Willie, 4.

1, Phoenix

Street, St Pancras. Edwin Arnott, brother, 30, Upholsterer. Emma Arnott,

sister, 34, Shoe-binder. Emily A., neice, 10. Phoenix Street was

near Equity Buildings where Sarah Arnott died in 1870.

1881 census.

6, New Street,

Chelmsford (The King William the 4th Inn). Benjamin Arnott,

lodger, 51, Hawker. b. Chesham.

13 George

Street, St Pancras. Edwin Arnott, 40, Upholsterer. Sarah Arnott, wife,

41, b. Cleeve, Glos. Ben Etheridge, visitor, 7, b. Mitcheldene, Glos.

22 March 1890.

Eleanor Arnott, wife

of Benjamin Arnott, Roadsman, died age 62 of Acute Bronchitis at 29

Chalk Farm Road. Daughter, M. Arnott.

11 January 1908

Benjamin Arnott, 77,

formerly a Hawker, of 43 Little George Street, St Pancras, died of

Bronchitis on 11 January 1908, at St Anne’s House, Streatham Hill.

St Anne’s

House was a branch of St Pancras Workhouse for some 500 aged and infirm

men.

|

|

References:

A History of the

Working Men’s Association from 1836 to 1850. George Howell, 1900.

Frank Graham, Newcastle, 1970.

A Memoir

of Thomas Martin Wheeler, by William Stevens. John Bedford Leno,

1862.

Charles

Booth’s notes for his Life and Labour of the People of London, a

selection digitised – and online – by the London School of Economics.

Illustrated London News, as cited.

Ragged

London in 1861, by John Hollingshead. Smith, Elder. Dent, 1986.

St Pancras

Workhouse Admissions Register, London Metropolitan Archives,

ST/P/DG/160/001.

The

Chartist Land Company, by A.M. Hadfield. David & Charles, 1970.

The

National Charter Association and its role in the Chartist movement,

1840–1858, by John Richard Clinton. M.Phil. thesis, Univ.

Southampton, 1980. This is a useful work to use in conjunction with the

main works on Chartism.

The

Northern Star

for the dates cited.

The Times,

as cited.

Further

information of the period from Harney’s Red Republican and

Friend of the People. But for a wider range of opinion, it is

necessary to consult the main published works on Chartism and other

radical newspapers of the time.

|

Acknowledgements: Linda

Hull for document research.

――――♦――――

MR. JOHN

BEDFORD LENO.

An article appearing in

THE COMMONWEALTH,

October 6, 1866.

John Bedford Leno is the eldest son of John and Phœbe

Leno, and was born at Uxbridge, on June 29, 1826. His mother kept

a dame school and from her be acquired his earliest educational

training. His academical course finished at the borough free

school, at the early age of eleven. Up to this period the family

income had been regular, if not large, some 12s. per week, if we have

been correctly informed. For this munificent sum, John Leno the

elder, wore the badge of slavery alias

the livery of his master, displayed a pair of calves (that exhibited no

signs of the rinderpest) and powdered his hair, till that near the

crown, with a dignity in keeping with its position, walked off and never

returned.

The particular circumstances, though somewhat

comical, that caused Mr. Leno, senior, to let go the sheet anchor, are

barely worthy of record. Suffice it to say, they culminated in a

determination to quit service for ever, a determination which he

heroically kept. The heraldic trimmings were secretly removed by

the subject of this brief sketch, and for months young Leno was rich in

buttons.

From eleven to fourteen, he fought his way as best he

could as cow-boy, rural postman, &c. His early ambition is

proclaimed by the fact, that about this period, he climbed a greasy pole

for a new white hat, and was within an ace of reaching it, when the

angry voice of his father bade him descend — that he kicked and wore the

stockings at Hillingdon fair on the ensuing year, and fought and made a

draw with Paddy Hardy, the boy champion of the town, who was some years

his senior.

It so happened that the office of post master, was

held by Mr. William Lake, printer. While acting as post-boy, his

conduct won him the good opinions of his master, and this resulted in an

offer on his part to teach him the business without a premium, the first

and last ever so taught by the Caxton of his native town. This was

probably the turning point of young Leno's life, for he was thus placed

in contact with men of far more than averaged scholarship, and moreover,

became a great favourite of Mr. Henry Kingsley, a gentleman well known

as possessing an extraordinary fund of information and a mind rarely

equalled. Here, moreover, he could fairly revel in light

literature, Lake's library being known for its completeness in this

department, and by way of change, stow himself away in the old

warehouse, where cartloads of unsaleable books were rotting away.

Here he studied "fistiana," through the pages of the Gentleman's

Magazine, and song literature by the accumulation of centuries.

The elder Disraeli's curiosities of literature and Barnum's museums

would sink into insignificance could the contents of this strange

warehouse ever be made known. Residues of unsold pamphlets,

illuminated missals which had been discovered by the stripping of old

books, in which the still older materials had been used up, a model

barrel made by a convicted murderer, by trade a cooper. His salary

during the period of apprenticeship, ranged from 3s. 6d. to 10s. weekly.

He left home during the second year of his apprenticeship and managed to

live for two years unaided on 4s. during the first and 4s 6d. during the

second year. Within a few days of the close of his apprenticeship,

his master became bankrupt, and, after waiting vainly several weeks for

a settlement of his master's affairs, he was compelled to go abroad in

search of work. In consequence of the collapse of the railway

mania, hundreds of printers were thrown out of employment, and both town

and country may be fairly said to have been overrun by them. The

result was, that he tramped thousands of miles, with no other income

save that derived from gifts made by the trade and the halfpence

collected from those who thought his effort as a singer worthy of

encouragement. In 1848, he returned home disheartened and

penniless. His friends suggested the propriety of a benefit at the

Town Hall, and the result was that both rich and poor attended, and

nearly £50 were collected by the transaction. With this he bought

press and type and in conjunction with Gerald Massey, a brother poet,

Edward Farrah, a shoemaker, and Mr. George Redrup, started a political

journal under the title of The Uxbridge Spirit of Freedom.

This journal attracted the attention or Mr. William Howitt, Mr. J. W.

Linton, and received the highest and encomiums from the London press.

The town clergyman, however, held other notions respecting its contents,

and poured forth the vials of his wrath on its youthful conductors.

At length advances were made to both Massey and Leno,

which induced them to join the Christian Socialists in their endeavour

to foster co-operative action on the part of working men. Massey

joined the working tailors of Castle-street, and J. B. Leno, the working

printers, of Pemberton-row. Both took an active part in the

political movements of the day and in the columns of the Christian

Socialist, and the reports of the public journals may be found good

evidences of their efforts in behalf of the political enfranchisement of

their own order and the amelioration of their social condition. At

the breaking up of the co-operative societies, J. B. Leno once more

sought employment as a journeyman. This continued for some two

years, when he had an offer of employment at Boston, in the United

States. To get there he sold everything he possessed, but when

about starting he received a letter, which somewhat modified the

original agreement. Before any understanding could be arrived at,

a portion of the money he had realised had vanished, and it was evident

that the rest would soon follow, if something was not done. In

this extremity, he determined once more to start as a master printer.

By perseverance and the kind assistance of the late Thomas Martin

Wheeler, and his brother George William, he surmounted his difficulties.

Hitherto we have said little, respecting those

persuits which have entitled him to this biographical notice. We

will briefly state that for years, he has been a recognised prose

contributor to democratic journals — among which may be mentioned,

The Spirit of Freedom, The Future,

The Christian Socialist, The Workman's Advocate, The

Commonwealth, &c.

When Eliza Cooke retired from the Dispatch

newspaper, the editor availed himself of the contents of a small volume

he had issued under the title of Herne's Oak, to supply the

weekly instalments of poetry. His "Song of the Spade," first

published in the Dispatch, attracted the attention, and excited

the warmest praise of Capern, the Bideford postman, who, on a friendly

visit to the author, proclaimed it one of the best labour songs ever

written. His 100 Songs of Labour (of which a new edition will

speedily be forthcoming) sold extensively among the labouring portion of

his countrymen, and we are told that several of the songs have become

exceedingly popular in the Great American Republic.

The following independent criticism places his merits

as a song writer beyond all doubt. Ernest Jones, in reviewing

them, said that the "Song of the Spade was equal to the lyrics of

Mackay." In Lloyd's he was called "The Burns of Labour."

By Reynold's the "Poet of the People," while the

Athenæum,

devoted two of its pages to a highly favourable review of

a penny issue.

The words, with the music by Mr. John Lowry, of

several, may be obtained at 282, Strand, price 6d. His later and

more ambitious efforts have a never yet been presented to the public in

a collected form. Mr. Leno is also known as a the writer of essays

on the Nine Hours Movement, on Female Labour, &c.

His activity in all movements in which he has a been

engaged is invariably recognised, and the estimation in which he is held

by his colleagues, in the present agitation for Reform, may be guaged by

the position he occupied on the poll for the Executive Council, which

will be found in another portion of our paper. Mr. Leno, is now in

his fortieth year, and we trust he will live on to enjoy the high

opinion in which he is held.

This notice would be far from complete did we not

present our readers with a poem. Hence we conclude with the

following picture of a Crowded Court, the original of which may be found

within a few yards of his own dwelling.

|

THE CROWDED COURT BELOW.

|

|

As I gazed from out my window on the crowded court below,

Where the sunshine seldom enters and the winds but seldom blow,

I behold a flow'ret dying for the want of light and air,

And I said, "How fares it, brothers, with the human flow'rets

there'!"

By and bye I saw a little hand stretched through a broken pane,

"I have brought thee," cried a little voice, a "cupful of God's

rain;"

But rain alone would not suffice to raise its drooping stem,

And I thought of those who dwelt below and longed to succour

them.

On the morrow, ere the noontide, as I wandered down the court,

Through a brood of little children, flushed alone by ruddy

sport,

I drew a little girl aside and bade her tell to me

The name of those who dwelt within the cottage numbered three.

With little bright eyes sparkling through her flaxen, unkempt

hair,

She answerers "I will tell you; there are many living there!"

And saintly with her nimble tongue she ran the whole list

through,

I gave the child a penny, and she curtseyed and withdrew.

Let those on Mercy's errands bent be never turned away!

There was fever raging all round those children in their play;

And in the little stifling room, outstretched upon the bed,

The sister hands to that I saw were lying cold and dead.

I called the flow'rets friend to me, and kissed her pallid brow;

I longed to bear her far away, where healthful breezes blow;

She told her tale of heartfelt grief as innocence can tell;

I never heard a tale so sad in sorrow told so well.

Toll, toll the bell! another and another has been slain!

No more shall I behold that hand stretched through the shattered

pane

They bear her to a sunny spot, where myriad flowers bloom—

The spot that should have been her home is chosen for her tomb!

But what of those yet left behind within that sunless court?

Shall they be left till Death shall come and end their childish

sport?

And she with flaxen, unkempt hair, with bright eyes all a-glow—

Shall she, like others, perish in the crowded court below? |

―――♦――― |