|

CHAPTER IV.

THE

MILLER

A CHEAT?

On the day of the battle of Lewes (14th May, 1264), during the

flight of Henry III’s troops before the victorious barons, Richard,

the king’s younger brother, took refuge in a windmill, barring the

door and for a while defending himself from the fury of his

pursuers. They jeered him, shouting, “Come out, you bad

miller! You, foresooth, to turn a wretched mill master,”

which suggests that from an early date the miller was not a

person held in high regard despite his importance to the welfare of

the community.

The Victorian image of the ‘hale and bold’ miller, who ‘wrought and

sang from morn till night’, was a romantic depiction. Although

the miller was a necessary member of our former rural communities,

he was often unpopular. Far from being the jolly red-faced

figure, clad in a dusty apron and with a song upon his lips, the

villagers often regarded him as cantankerous, mean-spirited and

sometimes a cheat. This view can be attributed in part to

Geoffrey Chaucer who, writing at the end of the 14th century,

bequeathed to millers for the next 500 years a reputation for

dishonesty that was undoubtedly supported by at least a grain of

truth.

Fig. 4.1: Robin the Miller,

from Chaucer’s Canterbury

Tales.

In The Reeve’s Tale, Chaucer depicts a coarse and lewd man,

who was often violent in the bargain . . . .

|

“A rumbustious cheat of sixteen

stone

Big in brawn, and big in bone,

He was a master hand at stealing grain

And often took three times his due

Because of feeling with his thumb,

He knew its quality.

By God! To think it went by rote,

A golden thumb to judge an oat!” |

Wealthier than the ordinary folk, the miller’s circumstances caused

jealousy and occasionally led to millers being targeted during bread

riots at times of famine. This arose from the system then

prevalent whereby the Lord of the Manor exacted ‘toll

corn’ from the peasants who were dependent upon the miller to

produce supplies of flour for their own use. Usually between

one-sixteenth and one twenty-fourth, it was an easy matter for the

miller to set aside more than the agreed toll and keep the surplus

for himself.

As late as the 1880s it was reported that Henry Liddington, the

miller at Goldfield mill at Tring, was charged and convicted with

taking excessive tolls. Frederick Eggleton, one of

Liddington’s customers, complained, and the matter went to court.

A report in the

Herts Mercury stated that . . . .

“. . . . it appeared that Eggleton’s wife

and children had gleaned a quantity of wheat, which when thrashed

weighed 232 lbs. This was taken to the defendant to grind, and

when the flour was returned it only weighed 108 lbs. Allowing

14 lbs. per bushel waste, which was a fair amount, there was thus 60

lbs. short. Being dissatisfied, Eggleton went to the defendant

and asked him for the offal, offering him at the same time 2s. for

the grinding of the wheat. The defendant declined to give up

the offal, and told Eggleton that he had received all the defendant

intended he should have.”

Found guilty, Henry Liddington was fined £10 plus costs. He

was probably was the last windmiller in Hertfordshire, if not in

England, to be convicted of this particular felony.

FOOD ADULTERATION

Besides cheating on weight, a dishonest miller might also adulterate

the flour. This was a more serious and potentially harmful

matter, but not uncommon throughout the food trade in bygone times.

In The

Expedition of Henry Clinker by Smollett (1771), a country

squire comments thus on London’s food . . . .

“The bread I eat in London is a deleterious

paste, mixed up with chalk, alum and bone ashes: insipid to the

taste and destructive to the constitution . . . the tallowy rancid

mass called butter is manufactured with candle-grease and

kitchen-stuff . . . .”

An example reported in The Northern Star in 1846, describes

how flour was adulterated with gypsum, a type of alabaster that

could be ground to a fine white powder. The report states that

a considerable quantity of gypsum was ground at a mill near Carlisle

before being sent to Liverpool. It was then traced to William

Pattinson of Cuddington Mill, near Weaverham, who was discovered by

officers in the act of mixing it with flour. The newspaper

ranted amusingly . . . .

“Thus is our ‘daily bread’ adulterated;

thus is the craft of the mason carried on in our very stomachs, and

mortar there produced which is of mortal effect; and thus a family

wishing to purchase a stone of flour, is literally furnished with a

flour of stone.”

For his crime Pattinson was fined £10 by Cheshire magistrates.

Further down the production line the bakers were also at it, using

alum (potassium aluminium sulphate, or potash, which in large

quantities is toxic) to bulk out flour while giving the bread a

whiter colour and causing it to absorb and retain a larger amount of

water than otherwise. This from the Hampshire Telegraph

(1804) . . . .

“Near 50 bakers have been convicted at the

different Police Offices within the last month, for selling bread

deficient in weight. Many of them were likewise fined for having

alum in their houses, with a view to mixing it with bread, a

practice extremely prejudicial, particularly to infants.”

Adulterating flour with alum remained a problem throughout the 19th

century, as this extract from a manufacturing journal of 1880

illustrates . . . .

“However happy the effects of alum may be

in improving the appearance of the bread and swelling the profits of

miller and baker, the effects upon those who are obliged to eat such

bread are liable to be most disastrous. . . . a very little alum in

bread may not prove immediately or seriously injurious, but no

considerable amount of such a powerful astringent is required to

disorder digestion and ruin health, as is shown by a vast array of

competent testimony.”

But there were occasions when millers did tamper with the grain with

good intention. This from a miller's handbook of 1881 . . . .

“A musty smell may be removed from grain by

mixing powdered coal with it and letting it stand for fourteen days,

at the end of which time the coal dust is removed by the purifying

machine. This treatment is said to remove every trace of mould, and

the flour is excellent.”

The reputation earned by millers endured to such an extent that

surprise was registered when an honest miller was encountered, as is

evidenced on a tablet in Great Gaddesden church, which reads . . . .

“. . . . In memory of Thomas Cook, late of

Noak Mill in this parish, who departed this life 8th December 1830,

age 77. He was a good Husband and tender Father, and an honest

man, although a miller.”

THE MILLER’S TRADE

In giving their miller a reputation for greed and dishonesty, his

contemporaries rarely appreciated that windmilling involved high

fixed costs. The great millstones had to be dressed and set

periodically, machinery broke down and windmills often suffered

storm damage, which was expensive to repair, if indeed the storm had

not brought about the mill’s complete destruction. And to add

to these risks and costs, windless periods would cause the mill,

quite literally, to grind to a halt.

|

%20-%20miller%20at%20Blackboys%20post%20mill%20Framefield%20East%20Sussex.jpg) |

|

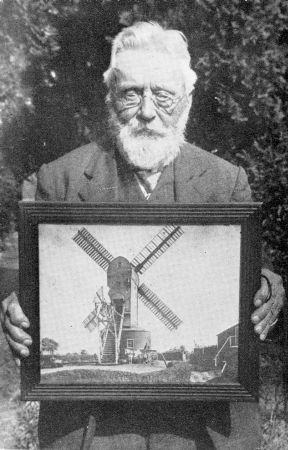

Fig. 4.2: two old

millers. Mr. J. B. Greater of Stratford St.

Andrew, Suffolk and

Mr. J. Paris of

of Blackboys post mill, Framefield, East Sussex. |

Millers who could not afford to maintain their millstones in the

most efficient working order had to make do with a more precarious

margin of profit. In his book Wheat and the Flour Mill

(1920), Edward Bradfield, had this to say about the tedious but

important process of dressing millstones . . . .

“. . . . half the miller's art — and it was

an art — was comprised in laying out and dressing the stone.

Properly to lay out a stone; to attain the absolute balance; to mark

out the quarters, lands, and furrows and, finally, to give the

requisite fineness of dress to the surface, required the skill and

judgment, and steadiness of hand and eye, of no mean order, and the

old stone millers rightly prided themselves on the quality of their

work.”

The millstones being set and dressed and the motive power being

available — which, for a windmill, cannot be taken for granted — the

process of milling can commence. The first task was to blend

the various varieties of wheat to produce flour of the required

character, then to rid the grain of impurities, such as stones,

twigs, alien seeds and other extraneous matter that would adulterate

the flour. This extract from an 1867 edition of The Miller

magazine describes the process at that time . . . .

“The art of

mealing, as it is called, consists in the judicious choice of wheat

and in the proper arrangement of the machinery, so that the whole of

the flour which the wheat is capable of producing may be obtained at

one grinding.

The proper proportions of the wheat for grinding are mixed in a bin,

after which the grain is passed through a blowing apparatus in order

to separate dust and light particles. It is next passed

through a smut machine, consisting of iron beaters enclosed within a

skeleton cylindrical frame covered with wire, the spaces being wide

enough to allow the impurities of the grain to fall through.

The beaters revolve 400 or 500 times in a minute and by their action

against the wires scrub the wheat, and remove portions of dust,

smut, and impurities.

After this, the wheat is passed through a screen, arranged spirally

on a horizontal axis, the revolutions of which scatter the seeds

over the meshes, and allow small shrivelled seeds to pass through.

The grain is next exposed to a current of air from a fan, which

completes the removal of chaff, dirt, smutt-ball, etc.

The result of all this elaborate cleaning is greatly to improve the

whiteness of the flour, and also its wholesomeness; and its

necessity is evident from the accumulation of impure matter in the

cases of the screens.”

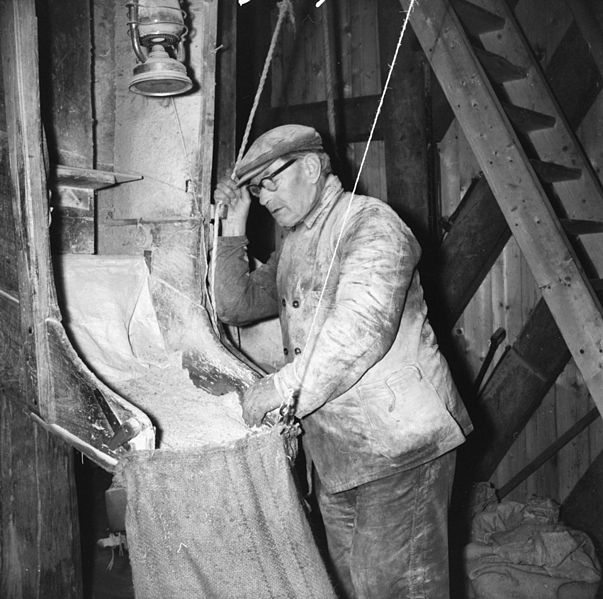

Fig. 4.3:

a miller bagging up the product.

As the wheat passes from the last cleaning machine, it falls down a

canvas tube into the hopper which supplies the millstones, where a

jigging kind of motion is kept up, so as to shake the corn into the

trough over the stones in equable quantities; and so long as this

action is going on properly, a little bell is made to ring, the

motion of which ceases with the supply of wheat.”

This activity supposed that the wind was blowing sufficiently to

drive the mill. Windless periods left the miller with a

growing backlog of grain and no income, so when a windy period

arrived it was usual for him to work day and night for several days

on end to get as much done as possible while the wind lasted.

It is unsurprising that even small country mills introduced small

steam engines to drive the equipment when these became available.

A TOUGH BUSINESS

As well as requiring great skill and experience, the miller’s work

was often arduous. Many worked ancient post mills fitted with

simple sails, tail-poles, and manually-tentered stones. The

miller had to be alert to any change in the wind; to an experienced

miller’s ear, the condition of the mill was evident from the sound

of its machinery, while badly-adjusted stones could be detected from

the smell of scorched meal (“nose to the grindstone”).

Working old mills especially, could prove challenging when wrestling

with wind and rain. When aware of a gathering storm, the

miller had to apply the brake and reef the sails, a task that could

take two men 30 minutes or more. Turning a post mill in a

strong wind was also a slow job and could be an exhausting one.

This was the experience of James Saunders, (1844-1935) who drove an

old post mill at Stone near Aylesbury (fig. 4.4) . . . .

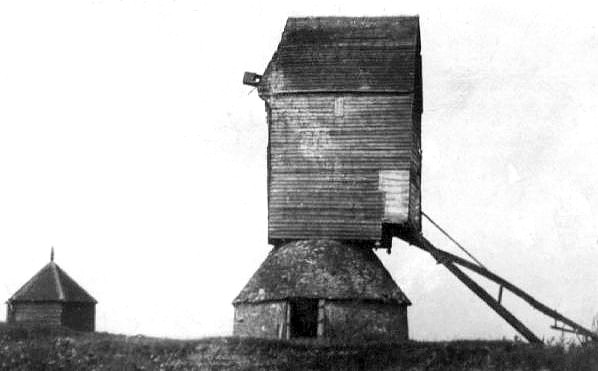

Fig. 4.4:

the remains of Stone post mill c.1900.

“Many a time when I was out shifting the

cloths in a storm [reefing the sails],

the water has run off them down my arms and out of my trouser legs.

Of course there was no chance of getting dry clothes until I went

home, and in the winter they have sometimes been frozen onto me for

hours . . . .”

In more modern mills, self-reefing patent sails eliminated this

arduous task.

Another aspect of milling that could, from time to time, make it a

tough business was competition with other millers. Here

Saunders reflects on a mill that he drove at High Wycombe . . . .

“. . . it was not a good neighbourhood and

already overrun by millers. There were ten flour mills in the

valley before we started; many of them paper mills converted into

flour mills during the bad spell for paper-making, but all of them

adding to the competition. Indeed when we began there was

almost as many millers as bakers.”

And so in a buyers’ market flour prices were driven down. This

from the Bucks Advertiser, April 1876 . . . .

“Bucks County Lunatic Asylum.

To Millers —

Persons willing to supply FLOUR (about 9 sacks per week) as set

forth in the printed forms of tender, for three months from the 18th

day of March 1876 are requested to deliver at the Asylum at Stone,

tenders on or before ten o–clock on the morning of Thursday the 16th

instant . . . . Addressed to the Committee of visitors of the Bucks

County Lunatic Asylum. A sample of flour will be shown at the

Asylum; and a sample must be sent with the tender.”

Another business risk that affected farmer and miller alike, was a

poor wheat harvest. For several years James Saunders lived on

the verge of bankruptcy, only surviving through the good offices of

a sympathetic bank manager . . . .

“No country miller is likely to forget

1879, the worst year by far that I have ever known. The crop

of English wheat was all bad alike, and country millers were

entirely out of the market. Moreover, the competition of

American flour became more severe; agents were travelling round

practically everywhere offering it to every little village baker.

Many mills were shut down at this time and never restarted again.”

DANGEROUS WORK

Great care had also to be exercised in working a mill in an age when

moving machinery was not always properly shielded, if at all, from

the unwary. This from the Hampshire Telegraph (1804) .

. . .

“A few days since, as John Ringer, aged 26,

was attending a boulting mill

[it sifts meal into flour, etc],

in a windmill belonging to Mr. Francis Bacon, of Dickleburgh, the

cogs caught hold of his frock smock, and so entangled him, that he

was carried round by the same for three hours, in which time he was

reduced to a most horrid spectacle.”

. . . . and from the Caledonian Mercury (1800) . . . .

“Yesterday evening the proprietor of the

mill at Holyrood, had both legs most dreadful fractured, by the

breaking of the millstone. Mr. Comins, the Staff Surgeon,

being sent for, found the limbs in so shattered a state, that he was

under the necessity of amputating both limbs immediately.”

For effective operation, windmills need a consistent draught with

minimal turbulence from the surrounding landscape. Thus, they

were often sited on isolated ground, but this left them more exposed

to damage by storms and lightning strikes, problems made worse by

their position generally being out of easy reach of water with which

to fight fires. This from The Standard (1829) . . . .

“During the thunderstorm on Thursday, the

windmill at Toot Hill, near Ongar, was struck with the lightning and

literally dashed to pieces; parts of it were driven nearly 100

yards, and the corn strewed about; and a man buried in the ruins has

since been got out alive, but dreadfully bruised. The leg has

been amputated . . . .”

. . . . two days later a further report of this incident appeared in

The Morning Chronicle, embellishing the earlier details by

informing readers that the victim was the miller . . . .

“. . . . and his right hand mangled in a

most frightful manner. . . . upon further examination, large

splinters of wood, and even grains of wheat from the hopper, were

found driven into various parts of his body.”

This from the Times (1954) . . . .

“One of the last four working windmills in

Lincolnshire, a county which at one time had over 400 in use, has

been struck by lightning . . . the sails crashed through an adjacent

engine house and were smashed to pieces . . . . and the foot thick

shaft was snapped off when the lightning struck.”

The absence of means to turn old post mills into the wind

automatically made them particularly prone to storm damage.

Indeed, both the post mills at Pitstone (see Chapters

V & VI)

were damaged beyond repair when struck from behind by sudden squalls

before they could be winded, the outcome being chaos to their

internal shafts and gearing before their sails were eventually torn

from their windshafts.

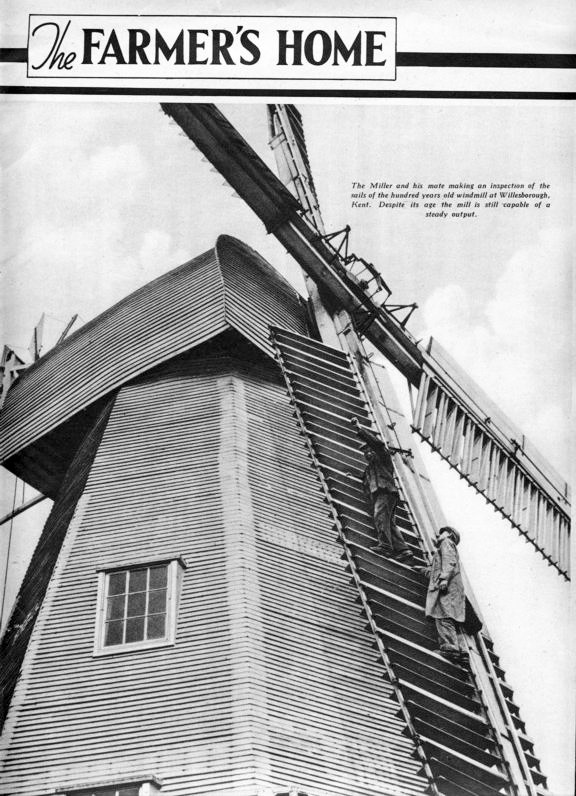

Fig. 4.5:

the miller and his mate inspecting the patent sails of Willesborough

mill, Kent.

This smock mill survives in full working order.

The vulnerability to storms of old windmills fitted with simple

cloth sails, is illustrated in this experience of James Saunders

while driving his post mill at Stone near Aylesbury . . . .

“A modern windmill is one thing, an

antiquated post mill 400 years old, as mine was said to be, is quite

another. . . . It was in October or November, at a time when I was

so busy I had not kept a proper lookout for storms . . . and a

tremendous hurricane caught me unawares. My first warning was

that the mill was running faster and faster, but I was not really

disturbed then until I had put the brake on and gone down to take

some cloth off. Outside it was as black as pitch. I felt

my way round to one sail and was just beginning to uncloth when the

gale came on like mad. It blew me against the round-house, and

away went the sails as if there was no brake on at all. I

shall never forget how I rushed back up the ladder. The whole

mill rocked so that the sacks of meal that were standing in the

breast were thrown down like paper, but I got to the brake lever

somehow and threw all my weight on it. I knew that if the

brake were kept on she was bound to catch fire, so I let her off,

and round she went, running at such a rate that the corn flew over

the top and smoke blinded and suffocated me. . . . The sparks were

flying out all round the brake as she groaned and creaked with the

strain, but it still didn’t stop the sails; and I doubt whether

anything could, had not the hurricane itself subsided as suddenly as

it sprung up.”

And storms did cause mills that had ‘run away’ to catch fire; this

from the Morning Post (1818) . . . .

“We this day give some further melancholy

details of the effects of the late violent storm . . . at Exmouth,

the violence of the gale carried round the vanes of the windmill

with such velocity as to cause the works to take fire, and the vanes

were ultimately blown off, and dashed to pieces.”

More substantially built tower mills fitted with patent sails and

with fantails (and thus less likely to be tail-winded), weathered

storms better, but when the sails were damaged, repairs could be

very expensive. To keep costs down, millers did what running

repairs they could themselves — particularly the lengthy task of

dressing the millstones — and only resorted to a millwright or the

village carpenter for specialist jobs.

“MAN KILLED

BY A WINDMILL — Last week a man named

James Messenger, was killed at Houghton Regis, by the sails of a

windmill. It appeared that whilst about his work there he

imprudently passed close to the sweeps of the sails to get to a

door, and one of the fans struck him on the back part of the head.

The poor man was struck to the ground with great violence and was

picked up insensible. His master rendered assistance and

forwarded a messenger to Dunstable for a surgeon, who, in

examination found that there was no fracture of the skull, but the

poor man was labouring under a severe concussion of the brain, and

in a few days after he died.”

Bucks Herald,

26th February 1842.

FIGURES OF SPEECH: RELICS OF THE MILLER’S TRADE

The millers of the past are not completely forgotten, although few

people realise this when they refer unknowingly to aspects of the

miller’s trade, for certain of their idiomatic expressions remain in

common use today:

Grind to a halt: refers to any process that will stop as a

result of a lack of materials or due to a breakdown in machinery.

In a mill, the millstones would literally “grind to a halt”

if the wind was not strong enough to drive them.

Show one’s metal/Show one’s grit: is a figure of speech that

today has more to do with demonstrating courage than experience,

although it derives from the latter. When a miller employed an

itinerant stone dresser to resharpen his millstones, the miller

invited him to display his tools and his hands for the miller’s

inspection to demonstrate his experience. The stone dresser’s

tools are made of iron, and the back of the hands and arms of an

experienced stone dresser would be blackened by the multitude of

embedded fragments of metal and grit from the task of resurfacing

the stones. Hence, to “show his metal”.

Rule of thumb: refers to the habit of the miller rubbing the

flour between his thumb and forefinger to assess whether it was too

coarse; if it was, he would reduce the gap between the grinding

stones to produce finer flour.

Grist to the mill: refers to a source of profit or advantage.

Grist is the grain brought to a mill to be ground. In the days

when farmers took grist to the mill the phrase would have been used

to denote produce that was a source of profit.

Keep your nose to the grindstone: means to apply yourself

conscientiously to your work. This might have derived from the

habit of millers, who checked that the stones used for grinding were

not overheating, by putting their nose to the stone in order to

smell any burning. But it is equally likely to have come from

the knife-grinder’s trade.

Run-of-the-mill: for a mill to produce flour of a consistent

output, the grain had to be of a certain quality, as had the milling

process. Thus flour that met whatever criterion that had been

set was described as run-of-the-mill, what we today might otherwise

describe as “standard”.

A millstone around one’s neck: is a Biblical metaphor meaning

a burden or large inconvenience one has to endure.

To be put, or to go through the mill: means to be exposed to

hardship or rough treatment, just like grain being ground.

Don’t drown the miller: little heard today, it derives from

the miller’s once crucial position in rural society in the

production of flour to make bread. This figure of speech was

intended to convey the value of an asset (however unpopular, as the

miller often was), for the obvious consequences of drowning the

miller would be to deprive the community of a vital, possibly even

life-sustaining, service. “Drowning” probably derived

from watermills and their millponds, being far more numerous than

windmills.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX I.

WHEAT FLOUR AND BREAD

Wheat flour is finely-ground grain. It is one of our most

important foods, for it is the principal ingredient in most types of

bread, biscuit and pastry.

Wheat probably developed from the accidental crossbreeding of

certain grasses, and by mutation. It was cultivated long

before the beginning of recorded history, archaeologists having

found evidence that it was grown in western Asia Minor at least

10,000 years ago. The ability to sow and reap cereals may be

one of the reasons that led man to live in communities, as opposed

to following a wandering life hunting and herding animals. The

Egyptians were to develop grain production along the fertile banks

of the Nile. By about 3,000 B.C. they had evolved tougher

varieties of wheat and had become skilful in baking bread.

|

|

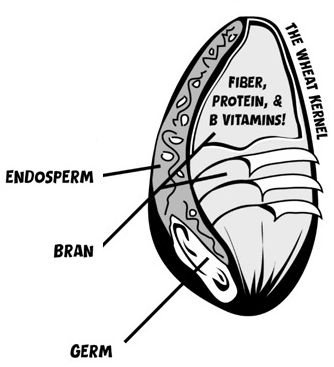

|

Fig. 4.6:

milling essentially separates bran and germ from

endosperm, reducing the endosperm to a uniform particle

size called ‘flour’. |

Wheat grain needs to be crushed to extract

the flour, but not all the grain is used. A grain of wheat

(the kernel) has three main parts; bran is the tough outer

covering; the embryo plant, or

germ, is found in the bottom of the kernel; the remainder is

the

endosperm, a material composed largely of starch with some

sugar. It is the endosperm alone that is used in the

commercial mass-production of white flour.

The first task to perform before wheat can be ground into flour is

to remove the heads from the top of the stalks. These are then

threshed, a process that removes the edible grains from the rest of

the head, called chaff. The grain is then ground to

separate the bran, endosperm and germ. The resulting meal

is sifted into various grades, white flour being the finest.

White flour contains only the endosperm, while wholemeal

flour contains all parts of the grain, which gives it a brownish

appearance. Although wholemeal flour is more nourishing it

suffers the disadvantages of a shorter shelf-life and, when used for

baking, a poorer rising characteristic than white flour.

The earliest type of bread is believed to have been made from grains

of wild grass, which were crushed by hand between two stones.

The resulting meal was mixed with water to form dough, which was

then baked on a stone over an open fire. This type of bread

would have been very coarse and heavy in texture.

Yeast is known to have been used by the Egyptians in around 4,000

BC, first in brewing and then in baking. Perhaps wild yeast

first drifted onto a dough that had been set aside before baking,

causing it to rise enough to make the bread lighter and more

appetizing than usual. This accidental process was then

reproduced deliberately. But a more plausible theory is that,

maybe by way of experiment, ale was used instead of water to mix the

dough. The rise would have been greater than from wild yeast,

and the effect would have been easier to explain and reproduce.

The Egyptians also invented the closed oven and bread assumed great

significance, being used instead of money; the workers who built the

pyramids were paid in bread.

By 1,000 BC, leavened bread had become popular in Rome, and by 500

BC a circular stone wheel turning on top of another fixed stone was

being used to grind grain; pairs of grindstones became the basis of

all milling until the late 19th century and are still used today in

the production of stone-ground flour. It is in this period

that the waterwheel was invented by the Greeks and later adopted by

the Romans who brought it to Britain.

During the Middle Ages, the growth of towns and cities saw a steady

increase in trade and bakers began to set up in business, with

bakers’ guilds being introduced to protect their interests while

controls also appeared to govern the price and weight of bread.

By Tudor times, bread had become a status symbol, the nobility

eating small white loaves, merchants and tradesmen wheaten cobs,

while the poor ate bran loaves (the most nutritious).

During the 18th century sieves made of Chinese silk were introduced,

which helped produce finer, whiter flour and white bread gradually

became more widespread. Tin from Cornish mines was used to

make baking tins resulting in bread (‘tin loaves’) that could be

sliced and toasted more easily and it was not long before the

sandwich was invented. At this time, and until well into the

Victorian age, bread was generally made from mixed grain; barley and

rye breads took longer to digest and were favoured by labourers

while the rich continued to eat the more expensive white wheat

bread.

In the early 19th century, cheap imported wheat was becoming

plentiful. To protect British grain prices and the income of

the landed gentry, the Corn Laws of 1815 imposed a high import

tariff on foreign-grown grain. The price of bread rose to as

much as 2s.6d. a loaf, when some wages were only 3s. shillings a

week. But despite the terrible suffering of the

disenfranchised poor, the Corn Laws were not repealed until 1846.

The 19th century also saw the introduction of town gas, which

replaced wood and coal to fuel bakers’ ovens, producing much more

even results, and the large automated baking units that followed

increased bread production significantly.

Today, 76 per cent of the bread we eat is white, with sandwiches

accounting for about half of this. Large bakeries producing

wrapped and sliced bread. It was introduced here in the 1930s

and accounts for 80 per cent of UK bread production. In-store

bakeries produce about 17 per cent and the remainder of the bread we

eat is sold in local bakeries.

Some traditional millers continue to use millstones, which unlike

the steel rollers used to mill mass-produced flour, allows the

miller to leave the whole grain intact, thereby adding a depth of

flavour to the flour. Most commercial flour has the germ

removed. Many independent bakers make a point of using

stone-ground flours grown in Britain and milled at smaller-scale

mills. The resulting bread has more character and flavour,

such as that produced in the small bakery attached to

Redbournbury Water Mill,

St. Albans (generally open to the public on Sunday afternoons).

――――♦――――

APPENDIX II.

GLEANING

Fig. 4.7:

‘The Gleaners’, by Gustave Doré (1832-83).

Gleaning is gathering grain left by the reapers. Some cultures

promoted it as an early form of welfare system and in this context

the Bible makes several references to gleaning, including

Deuteronomy (24:19–21), which states the law thus . . . .

“When you are harvesting in your field and

you overlook a sheaf, do not go back to get it. Leave it for the

alien, the fatherless and the widow . . .”

. . . which led to one poor biblical widow meeting her husband to

be, for the romance between Ruth and the wealthy Boaz (Ruth 2) first

sparked into life when Boaz caught sight of Ruth gleaning in his

field after the reapers, as depicted by Doré (fig. 4.).

But gleaning did not always have a happy ending and until well into

the 19th century it could lead to the prison cell. Under the

heading A WOMAN IMPRISONED FOR GLEANING, the Birmingham Daily

Post, 12th August 1868, carried a report of a “poor woman”

imprisoned by Chester Magistrates. The newspaper informed its

readers that a certain farmer had complained: “I have had such a

great deal of damage I want to make an example.” And an

example their honours duly made; “You must go to jail for seven

days,” was the verdict of the bench, but on sentence being

passed one of the magistrates had second thoughts . . . .

“‘I won't be a party to that. Seven

days! All the papers in the country will be down us.’

The defendant turned very pale, and, bursting into tears, said,

‘Seven days for that! Don't send me to gaol from my four poor

children, and one sucking at the breast.’”

Meanwhile the farmer was also back-tracking, for while he wished for

some punishment “he did not ask for so much as that”.

The commotion that followed caused their honours to reconsider,

following which the sentence was reduced to a fine of 5s.6d. damages

with 8s. costs (the wage of a farm labourer at that time was around

10s. a week); but as the defendant could not pay, she served three

days in jail.

Fig. 4.8:

‘Gleaners’, by Jean-François Millet (1814–75).

Despite the threat of jail, gleaning was commonplace, although

subject to local rules as this extract from the Farmer's Handbook

of 1814 describes . . . .

“The custom of gleaning is universal, and

very ancient: in this country, however, the poor have no right to

glean but by permission of the farmer; but the custom is old and so

common, that it is scarcely ever broken through. It much

behoves the farmer, in some places, where it is carried to excess,

to make rules for the gleaners, and not to suffer them to be broken,

under any pretence whatever.”

Each area of the country had its own customs, for instance at Gamnel

Wharf mill in Tring, there was a day set aside to grind ‘gleaners’

corn’, the cost of which was paid by keeping the bran, or,

alternatively a quart out of a bushel of wheat. This old

tradition worked well, except when the treatment of a gleaner was

not scrupulously honest, as in the case of Frederick Eggleton and

the miller of Goldfield described above.

Gleaning remained an extremely important feature of rural life until

the beginning of the 20th century, especially in times of

agricultural depression when farm work was scarce. Many

villagers relied on the flour that was derived from their autumn

gatherings in the wheat fields to last the family throughout the

year. |