|

CHAPTER XV.

WINDMILLS IN LITERATURE

IN PROSE

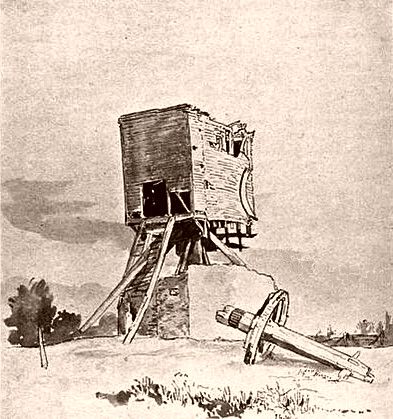

Fig. 15.1: Middleton Road post

mill, Bicester c.1880.

Built c.1675, blown down in 1881.

Could there be a more picturesque reminder of old English life, or

any feature in more perfect harmony with its rural surroundings,

than a venerable old wooden windmill? Whether standing on a

far hilltop or on a gentle rise in the valley, its place in the

picture was always pleasing, often its centre of attraction.

In the opinion of Robert Louis Stevenson (The Foreigner at Home)

. . . .

“There are, indeed, few merrier spectacles

than that of many windmills bickering together in a fresh breeze

over a woody country; their halting alacrity of movement, their

pleasant business, making bread all day with uncouth gesticulations,

their air, gigantically human, as of a creature half alive, put a

spirit of romance into the tamest landscape.”

Such romantic scenes live now only in pictures. Here, Walter

Rose (The Village Carpenter) describes the exhilaration he

experienced as a child, standing before those selfsame uncouth,

gesticulating sails . . . .

“The sails always reached to about two feet

from the ground, and it was an enthralling experience to stand

before them, as I often did, when a stiff wind was blowing, and

watch them go roaring by: to note the ‘swoop,’ ‘swoop’ of each sail

as it passed and to follow the orbit of one as it rose to almost

sixty feet in the air, immediately to descend and swiftly pass

again.”

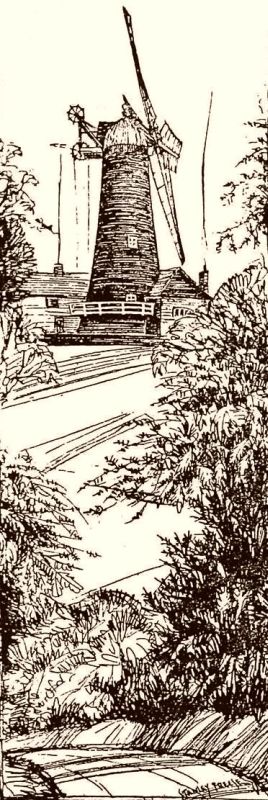

Fig. 15.2:

frontispiece,

Lettres de mon Moulin.

In Lettres de mon Moulin, Alphonse Daudet reflects upon the

disappearing windmill and the way of life that once centred upon it

. . . .

“At one time there was a great milling

trade, and from thirty miles around the people of the mas brought us

their wheat to grind. . . .

All about the village the hills were covered with windmills.

Right and left your eye fell upon arms revolving in the mistral

above the tops of the pine-trees, upon endless numbers of little

donkeys laden with sacks, trotting up hill and down dale along the

roads; and the whole week through it was a pleasure to hear on our

hill-top the cracking of whips, the flapping of the arm-sails, and

the ‘gee-up’ of the millers’ boys. . . . On Sundays whole parties of

us used to go up to the mills, where the millers treated us to

Muscat wine. Their wives were like queens, decked out in all

the bravery of their lace scarves and gold crosses. I used to

bring my fife, and until black night there was dancing and

farandoles. These mills, you see, were the joy and the wealth

of our countryside.

Unfortunately, some Frenchmen from Paris conceived the idea of

establishing a big steam-driven mill on the Tarascon road.

There’s always a craze for

anything new! People got into the habit of sending their corn

to the steam mills, and the poor windmills were left without any

work to do. For some time they tried to struggle on, but steam

proved the stronger, and one after another, alas! they had to close

down . . . . No more little donkeys. . . . The handsome millers’

wives sold their gold crosses . . . . No more Muscat wine! No more

farandole! . . .”

Apart from Muscat and farandoles, a miller’s life could be hard, as

is portrayed by Julia Ewing in Jan of the Windmill . . . .

“In a coat and hat of painted canvas, he

had been in and out ever since the storm began; now directing the

two men who were working within, now struggling along the stage that

ran outside the windmill, at no small risk of being fairly blown

away.

He had reefed the sails twice already in the teeth of the blinding

rain. But he did well to be careful. For it was in such a storm as

this, five years ago ‘come Michaelmas’, that the worst of windmill

calamities had befallen him, — the sails had been torn off his mill

and dashed into a hundred fragments upon the ground. And such

a mishap to a seventy feet tower mill means — as windmillers well

know — not only a stoppage of trade, but an expense of two hundred

pounds for the new sails . . . . That catastrophe had kept the

windmiller a poor man for five years, and it gave him a nervous

dread of storms.”

Fig. 15.3:

Don Quixote tilting at a windmill, by Gustave Doré.

The most famous episode in all of literature to feature windmills

must surely be that which appears in Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote.

In one of his adventures, the Don imagines the sails of a group of

windmills to be the waving arms of giants. This famous scene

gives rise to the idiom “tilting at windmills”, meaning to

attack imaginary enemies or to fight futile battles. The word

‘tilt’, in this context, comes from jousting, which is precisely

what the Don’s fevered imagination leads to . . . .

“Just then they came in sight of thirty or

forty windmills that rise from that plain. And no sooner did

Don Quixote see them that he said to his squire, ‘Fortune is guiding

our affairs better than we ourselves could have wished. Do you

see over yonder, friend Sancho, thirty or forty hulking giants?

I intend to do battle with them and slay them. With their

spoils we shall begin to be rich for this is a righteous war and the

removal of so foul a brood from off the face of the earth is a

service God will bless.’

‘What giants?’ asked Sancho Panza.

‘Those you see over there,’ replied his master, ‘with their long

arms. Some of them have arms well nigh two leagues in length.’

‘Take care, sir,’ cried Sancho. ‘Those over there are not

giants but windmills. Those things that seem to be their arms

are sails which, when they are whirled around by the wind, turn the

millstone.’”

Fig. 15.4: Paul Joseph

Constantin Gabriël, English Landscape with Mills.

――――♦――――

IN VERSE

More classical allusions to windmills appear in Shakespeare. In

Henry IV Part I, Act 3, Harry Hotspur says to Mortimer, Earl

of March . . . .

|

“. . . . .

O! he’s as tedious

As a tired horse, a railing wife;

Worse than a smoky house. I had rather live

With cheese and garlic in a windmill, far,

Than feed on cates and have him talk to me,

In any summer-house in Christendom.” |

But a cheese and garlic sandwich might go down remarkably well in a

windmill, particularly if during the repast one can gaze down on

acre upon acre of wheat, barley, oats or whatever, with a flock or

herd grazing here or there and the odd farmhouse dotted about the

patchwork sea of colour. Falstaff and his companions would

surely have revelled to their heart’s content in cheese and garlic

perched in such a position, for in the second part of Henry IV

Act 3, Justice Shallow remarks to this bulky man, who had “a kind

of alacrity in sinking” . . . .

"O, Sir John, do you remember since we all

lay at night in the windmill in Saint George’s Fields? . . . . Ha,

it was a merry night!"

The Anglo-French writer Hilaire Belloc actually owned a working

smock mill; Shipley Mill in Sussex formed part of an estate that he

bought in 1905. Belloc employed a miller, and windmilling

continued there until 1926. Thereafter he maintained the

fabric but, following his death in 1953, the mill was found to be in

a sad state of repair. It was then that friends raised money

to restore it as a tribute to the writer.

Fig. 15.5:

ruined post mill at Stratford, 1901.

Halnaker (pronounced Ha’nacker) Mill, the subject of this melancholy

poem from 1912, stands on Halnaker Hill north-east of Chichester.

In the poem, Belloc reflects on the collapse of the mill (struck by

lightning), which he uses as a metaphor for the decay of the

prevailing moral and social system.

|

HA’NACKER MILL

Sally is gone that was so kindly,

Sally is gone from Ha’nacker Hill

And the Briar grows ever since then so blindly;

And ever since then the clapper is still . . .

And the sweeps have fallen from Ha’nacker Mill.

Ha’nacker Hill is in Desolation:

Ruin a-top and a field unploughed.

And Spirits that call on a fallen nation,

Spirits that loved her calling aloud,

Spirits abroad in a windy cloud.

Spirits that call and no one answers —

Ha’nacker’s down and England’s done.

Wind and Thistle for pipe and dancers,

And never a ploughman under the Sun:

Never a ploughman. Never a one. |

In The Windmill, Robert Bridges describes the miller in

situ, account book in hand, thus laying emphasis on the

commercial realities of a miller’s life. His descriptive

details with “creaking sails” and “shuddering timbers”

conjure up a vision that anyone who has visited a working windmill

will recognize.

|

|

THE WINDMILL

The green corn waving in the dale,

The ripe grass waving on the hill:

I lean across the paddock pale

And gaze upon the giddy mill.

Its hurtling sails a mighty sweep

Cut thro’ the air: with rushing sound

Each strikes in fury down the steep,

Rattles, and whirls in chase around.

Beside his sacks the miller stands

On high within the open door:

A book and pencil in his hands,

His grist and meal he reckoneth o’er.

His tireless merry slave the wind

Is busy with his work to-day:

From whencesoe’er he comes to grind;

He hath a will and knows the way.

He gives the creaking sails a spin,

The circling millstones faster flee,

The shuddering timbers groan within,

And down the shoots the meal runs free.

The miller giveth him no thanks,

And doth not much his work o’erlook:

He stands beside the sacks, and ranks

The figures in his dusty book. |

|

Fig. 15.6:

Hawridge tower mill,

by Stanley Freece. |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 15.7:

the Miller’s

Daughter,

by Herman

Winthrop Peirce (1891). |

Alfred Lord Tennyson follows Bridges’

allusion to the miller’s grip on the world of business. Here,

he describes a prosperous and contented man, but one “full of

dealings with the world”. . . .

|

THE MILLER’S DAUGHTER

I see the wealthy miller yet,

His double chin, his portly size,

And who that knew him could forget

The busy wrinkles round his eyes?

The slow wise smile that, round about

His dusty forehead drily curl’d,

Seem’d half-within and half-without,

And full of dealings with the world? |

As for the miller’s daughter, the Laureate’s feelings, tenderly

expressed, are thus . . . .

|

It is the miller’s daughter,

And she is grown so dear, so dear,

That I would be the jewel

That trembles in her ear:

For hid in ringlets day and night,

I’d touch her neck so warm and white . . .

. . . . And I would be the necklace,

And all day long to fall and rise

With her laughter or her sighs:

And I would lie so light, so light,

I scarce should be unclasp’d at night. |

With so much grain in evidence, the risk of a vermin infested mill

is a real problem. Here, Walter de la Mare pays recognition to

the miller’s countermeasure . . . .

|

FIVE EYES

In Hans’ old mill his three black cats

Watch his bins for the thieving rats.

Whisker and claw, they crouch in the night,

Their five eyes smouldering green and bright:

Squeaks from the flour sacks, squeaks from where

The cold wind stirs on the empty stair,

Squeaking and scampering, everywhere.

Then down they pounce, now in, now out,

At whisking tail, and sniffing snout;

While lean old Hans he snores away

Till peep of light at break of day;

Then up he climbs to his creaking mill,

Out come his cats all grey with meal —

Jekkel, and Jessup, and one-eyed Jill. |

. . . . and not to forget the source of the windmill’s motive power;

this by Christina Rossetti . . . .

|

WHO HAS SEEN THE WIND?

Neither I nor you.

But when the leaves hang trembling,

The wind is passing through.

Who has seen the wind?

Neither you nor I.

But when the trees bow down their heads,

The wind is passing by. |

Reference was made in Chapter IX

on Hawridge windmill, to the writer Gilbert Cannan who rented the

mill after its conversion to private living accommodation. In

his study at the very top of the mill, he wrote copiously, including

a book of verse from which this extract is taken . . . .

|

ADVENTUROUS LOVE AND OTHER

VERSES

I have a room wherein each day I sit

Word-weaving. I have windows south, east,

west,

And with the changing sky my eyes are blest

Over this wide Heaven I let my wit

And fancy roam. My thoughts like birds do flit

Against the clouds in happy, happy quest

Of straws and twigs and moss to build their nest.

This is the spring when days with love are lit. |

Amateur poets have also paid tribute to windmills. This

anonymous sonnet pictures a feudal landlord and owner of a windmill

— to which his tenants are obliged to take their grain — reflecting

on his idle way of life, as idle as the slumbering landscape that

surrounds him. He tries to create an impression of industry

for the “bustling world” to see, but guilty conscience or not

the landlord collects his toll, which his miller deducts “in kind”.

Fig. 15.8:

smock mill.

|

THE LANDLORD’S TOLL

I pause to gaze across the weald —

There seems to be no life astir

Save a skylark soaring in the air

Caroling o’er a wheat-filled field;

And on this landscape, patch-worked jade,

Stillness lies; no other life is visible

But the slow-winding sails of my old windmill

Play flitting change with sun and shade.

In this place I follow my idle way,

As the bustling world would judge it,

Like a windmill I twirl my arms all day

And try to look committed.

Though I toil not for

what we grind

The miller mulcts my toll

in kind! |

James Edwin Saunders was a miller from Slough. He died in

1935, aged 91, after a lifetime spent in windmilling that brought

him immense satisfaction in spite of once being on the brink of

bankruptcy. James kept a diary in which his conflicts and

consolations are recorded, mostly in rhyme; one of his long poems,

which sums up his feelings for his craft, begins . . . .

|

MUSIC OF THE MILL

There is poetry in Milling, when one’s heart is free

From the care that blinds one’s vision — oft ‘twas so

with me

To a large extent, though even in those anxious

days

There were times when I had glimpses of its

transient rays.

How I like to see good running and due pleasure found

In the Mill’s efficient working, as I walked around.

When I went to bed I saw it still before my eye,

Still I heard the music stealing like a lullaby,

Soothing me to sleep and dreamland like an evening

psalm,

After days of busy effort, like a restful balm. |

Another amateur poet, H. E. Howard, from Chesham, wrote 50 Poems

of Buckinghamshire. A few lines from the beginning of one

of these poems, written in 1935 . . . .

|

HAWRIDGE COMMON

At noon among the rolling hills I strayed

And watched the

bearded ploughman. In the

vale

The February sun sang out and strayed

Up o’er the bramble slope until the sail

Of that old windmill tried to live again.

The wind tip-toed on every blade of grass;

And shimmering ponds as smooth

as smoothest glass. |

Fig.

15.9:

Le Monde vu par les artistes (p.11), René

Joseph Ménard (1881).

The last poem needs little introduction, for it must be the best

known of what windmill poems there are, and one of Henry Wadsworth

Longfellow’s most enduring . . . . |