|

|

|

|

Fig. 5.2: Sir

William Fairburn,

civil engineer. |

The 19th century civil engineer, Sir

William Fairbairn (1789-1874) [5]

began his working life as an apprentice millwright at

Newcastle-upon-Tyne. In his Treatise on Mills and Millwork

(1865), Fairbairn provides an interesting insight into the

millwright’s work during the 18th century:

|

“. . . . the millwright of the last century

was an itinerant engineer and mechanic of high reputation. He

could handle the axe, the hammer, and the plane with equal skill and

precision; he could turn, bore and forge with the ease and despatch

of one brought up to these trades, and he could set out and cut in

the furrows of a millstone with an accuracy equal or superior to

that of the miller himself. These duties he was called upon to

exercise, and seldom in vain, as in the practice of his profession

had he mainly to depend upon his own resources.” |

Thus, the millwright’s trade combined elements of those of the

carpenter, blacksmith and stone mason, while he needed to be of a

practical and resourceful turn of mind. His occupation also

demanded the ability to design mills and milling machinery, which

required the application of arithmetic and geometry to the

manufacture of all the components of a working mill. Fairbairn

tells us that . . . .

“. . . . he could calculate the velocities,

strength, and power of machines, could draw in plan, and section,

and could construct buildings, conduits, or watercourses, in all the

forms and under all the conditions required in his professional

practice. . . ."

During the windmill era, the millwright performed much of the work

of today’s civil engineer and it is not difficult to see why some of

the more gifted among their ranks became our first great civil

engineers. Expertise also flowed in the opposite direction.

John Smeaton, famous for the Eddystone Lighthouse (and the first to

proclaim himself a “civil engineer”), while not a millwright

by trade, performed valuable research into the design of milling

equipment. He investigated sail design and was the first to

employ cast iron in place of wooden parts in the construction of

milling machinery.

Fairbairn also tells us something about the millwright’s standing in

society . . . .

“. . . . living in a more primitive state

of society than ourselves, there probably never existed a more

useful and independent class of men than the country millwrights.

The whole mechanical knowledge of the country was centred amongst

them, and, where sobriety was maintained and self-improvement aimed

at, they were generally looked upon as men of superior attainments

and of considerable intellectual power.”

Perhaps Fairbairn’s opinion was rose-tinted, for the two local

millwrights for whom we have been able to obtain information, while

offering the range of skills that he describes, do not appear to

have matched them with a high degree of business acumen.

THE DECLINE OF THE MILLWRIGHT’S TRADE

As the Industrial Revolution progressed, millwrights were pressed

into service to build the first powered textile mills. James

Watt’s condensing steam engine developed into an economical and

reliable driving force and, unlike wind and water power, one that

offered a stable source of motive power. Gradually, wind and

water mills were replaced, first by steam-driven machinery and

eventually by electric power, while small local grain mills gave way

to large factory units catering for entire regions of the country.

As for the millwright, his work was mostly lost in the evolution of

other trades, such as turners, fitters, machine makers and

mechanical engineers.

LOCAL MILLWRIGHTS

THE HILLSDONS OF TRING

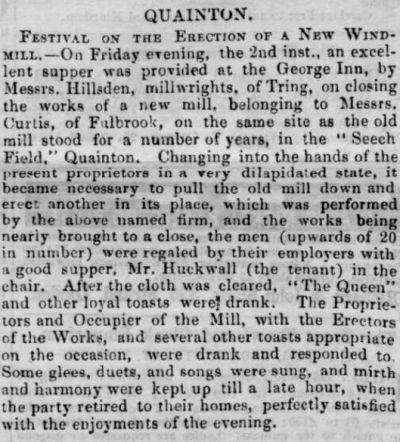

Fig. 5.3:

Bucks Herald, 10th November 1855.

Waddesdon-born John Hillsdon came to Tring in about 1825. The

1841 Census records him living at Tring Wharf with his wife and five

children, where he worked as a miller at Gamnel Wharf mill (Chapter

VII) together with his 16-year old son, John.

By 1850 John had left Gamnel to trade on his own account, describing

himself as a ‘Millwright’ and occupying premises on the corner of

Chapel Street and King Street in Tring. Ten years later the

Hillsdon’s venture into the world of business had proved unwise, for

their financial affairs were in a parlous condition. On 15th

December 1860 an announcement appeared on the front page of The

Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News:

|

|

|

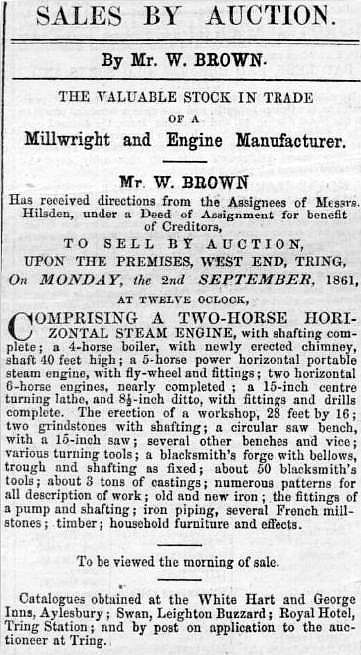

Fig. 5.4: Bucks Herald, 24th August 1861.

Bankruptcy sale of Hillsdon’s assets. |

|

“Notice is hereby given that by indenture

dated the 7th day of December 1860, John Hillsdon the elder and John

Hillsdon the younger of Tring, in the County of Hertford, Engineers,

assigned all their personal estate and effects whatsoever and

wheresoever to William Smith Simkin of No 6 Leadenhall Street,

London, Ironmonger, and John Nevins of Nos 1 & 2 Great Guildford

Street, London, Ironmonger, upon Trust for the benefit of

themselves, and all the creditors of the said John Hillsdon the

elder and John Hillsdon the younger . . . . In the presence of John

Merritt Shugar of Tring, Solicitor.” |

In spite of this drastic measure, in the following year Johns senior

and junior — now described as agricultural machine makers — are

found in the records of the Hertford Union Gaol & House of

Correction, imprisoned for debt. By no means an uncommon

offence at that time, the Hillsdon’s fellow inmates were other

assorted traders, including a china dealer, a market gardener and a

straw hat maker.

In May, 1861, John Jnr. petitioned for his discharge, his debts

amounting to £587. 14s, offering to pay 10s in the pound. All

his creditors concurred, save one, a solicitor, to whom Hilsdon owed

£21, but the objection was set aside and John was discharged.

What happened to his father is unrecorded, but they weathered the

storm and returned to carry on business in the same premises as

before. In 1869 John junior placed an ambitious advertisement

for Tring Iron Works in Kelly’s Trade Directory, where he is

described as “engineer; millwright; manufacturer of portable and

fixed steam engines, water wheels; corn, bone, bark and colour

miller; and iron and brass founder”. No more is heard of John

junior in Tring, but it is believed that he and his wife emigrated

to New Zealand, leaving there seven years later for the USA.

George Hilsdon, a younger son, also followed the family tradition

and remained with his father at the King Street business.

The firm of Hillsdon was undoubtedly involved in a wide range of

mill-related business, but all that is now known is that they

erected the tower mill at Hawridge Common (Chapter

IX), installed the steam engine at Wendover windmill (Chapter

X) and were possibly involved in the construction of Goldfields

and Waddesdon mills. [6] John

senior is last recorded in 1871, a widower of 76 living in lodgings

in Frogmore Street, Tring. It is believed that the Hillsdon’s

firm, Tring Ironworks, closed around 1905.

WILLIAM COOPER OF AYLESBURY

Almost all that is known of William Cooper and his business are

contained in two account books now held in the Buckinghamshire

Archives.

On October 11th, 1831, an announcement in the London Gazette

stated that the partnership between William and Joseph Cooper,

Millwrights and Smiths of Aylesbury, Bucks, had been dissolved by

mutual consent. The following year William Cooper was declared

bankrupt, his two account books passing into the custody of the

court. One is a general ledger in which are recorded his

business transactions between May 1827 and September 1832, the other

records expenses incurred between April 1830 and January 1831 in

connection with fitting out Champness windmill at Fulmer.

In common with the Hillsdons, the ledger shows that Cooper performed

a surprising range of work. This extended from simple repairs

to stoves and locks, to more complex work on agricultural machinery,

through to the installation of all the equipment at Fulmer and

Quainton windmills. The ledger also shows that Cooper worked

on some thirty wind and water mills in and around Aylesbury,

including a windmill at Tring (but unclear which) and those at

Waddesdon (Chapter XIV),

Wingrave (Chapter XIV), and

Wendover. He also undertook work on the treadmill in Aylesbury

Gaol and on an unspecified type of mill at Winslow Workhouse.

The cost of fitting out Champness mill was £445 8s.10d., of which

almost half was for labour, the balance being for canvas (121

yards), tacks (22,000), screws (13 gross), nails, chisels, ironwork,

timber, and “Different things”. Wages paid to the

skilled men were four shillings a day, while the daily rate for the

two labourers was two shillings.

Among Cooper’s smaller jobs are recorded the repair of butter

churns; roughing of horse shoes; mending wagons; repairing a kitchen

range; mending a rat trap; ringing pigs; mending plough shears; and

to a Mr. Collins he supplied “12 stoves different sizes”.

If nothing else it seems that the millwright of the age was

versatile.

What led to Cooper’s bankruptcy is unknown, although in the Fulmer

book there are references to expenses of a legal nature: “Copy of

a Rit” (writ), expenses for “Sherrfs officer”, and “Lawyer

Charge”, which suggest that he might have been owed money for

work on the mill. There are also several entries that refer to

the purchase of pints and quarts of gin and rum.

Apart from these account books, the Aylesbury Poor Rate Book for

1831-2 records that Cooper’s premises were in Walton Street on a

site now occupied by the White Swan, but by 1835 the foundry had

gone. |