|

CHAPTER III.

HOW A WINDMILL WORKS

INTRODUCTION

Little change occurred in windmill design from their first use in

Britain until the Industrial Revolution, when a number of

significant advances were made in the design of sails and machinery.

But important though they were, these advances were slow to gain

acceptance and too late to make a significant impact, for by then

James Watt’s condensing steam engine was in the ascendant.

From about the mid-19th century, steam-powered milling began rapidly

to supplant wind and water power. This was followed by the

introduction of industrial-scale flour mills in which steel rollers

replaced grindstones to produce, in greater quantity, finer and more

consistent quality products. Mead’s (later Heygates) Flour

Mill at Tring (Chapter VII) is an

early example of an industrial-scale flour mill.

This chapter describes the general operation of a windmill and some

of the advances in design that were made towards the end of the

windmill era. A brief description of the modern roller mill is

given in the Appendix.

WHAT A WINDMILL DOES

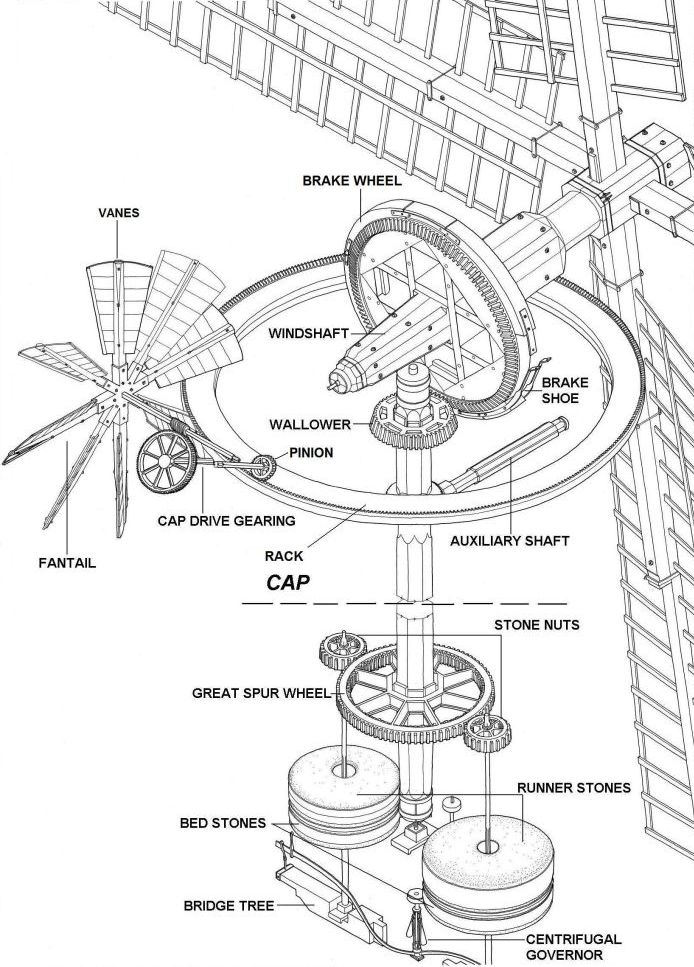

Fig. 3.1:

the fantail (where one is fitted) rotates the cap

automatically to keep the sails facing the wind.

The mill was the first engine invented by man. For centuries,

mills driven by water or wind were the only machines that could

convert the power of nature into useful work. In the case of

the windmill, wind striking its sails exerts a force upon them that

causes the shaft to which the sails are attached to rotate.

What then follows depends on what task the windmill is to perform.

Windmills have been used for many purposes, such as pumping water,

sawing wood and as crushing machines in the preparation of oil,

paper, spices, chalk and pottery. Today, wind turbines are

used increasingly to generate electricity. But in Britain, the

windmill’s most common use over the centuries was to grind grain.

In a grain mill, the wind’s energy, harnessed by the windmill’s

sails, is transferred via a system of shafts, cogs and belts to

drive one or more pairs of millstones. Grain, fed between the

rotating millstones is ground into meal.

The remainder of this chapter describes the main steps in the

windmilling process; also the sails and the machinery that is

usually found within a windmill.

THE FLOORS OF A WINDMILL

Fig. 3.2:

schematic drawing of a tower mill.

Windmills do not follow a common design but they do share common

features, not least of which is that windmilling is a gravity-driven

process. Milling begins at the top of the mill and each

succeeding stage of the process is performed on the next floor down

(in following this process, the need for a mechanically powered

hoist to lift sacks of grain and meal up several floors of a

windmill soon becomes clear!)

Windmills were built with different numbers of floors, [3]

hence, the windmilling process is not always exactly as described

below. However, in general the following applies . . . .

i. The cap, uppermost part of a windmill (fig. 3.1), houses the

windshaft, bearings, cogs and the top of the upright shaft, which

transmits the windshaft’s rotary motion down through the mill to

drive the machinery.

ii. The dust floor (fig.3.2), positioned under the cap, serves to

keep dirt from above from falling into the storage bins and to keep

dust rising up from below.

iii. The bin floor houses bins in which are stored grain for

cleaning; cleaned grain for milling; and meal to be sifted.

iv. The stone floor houses grain-cleaning machinery, the millstones

used to grind the grain, and machinery to sift the ground meal into

various grades of fineness.

v. The meal floor houses chutes from the stone floor above, down

which flows cleaned grain for milling, meal for sifting, and milled

products, each of which is collected in sacks.

THE WIND MILLING PROCESS

The first step in the milling process is to hoist the grain to be

milled up to the bin floor where it is loaded into a storage bin

ready to be cleaned. When required, the uncleaned grain is

discharged down a chute to the stone floor, where it is mechanically

cleaned, then discharged down a chute for collection on the meal

floor.

Sacks of cleaned grain are hoisted up the mill to the bin floor,

where they are stored in a bin ready for milling. When

required, the cleaned grain is discharged down a chute into a hopper

on the stone floor, from where it is trickled into the millstones,

ground and discharged down chutes for collection on the meal floor.

The sacks are then hoisted up the mill to the bin floor, from where

the meal travels downwards, this time through a flour dresser, which

sorts and distributes it according to its fineness, white flour

being the finest and bran the coarsest. All this machinery is

powered by the thrust of the wind as harnessed by the windmill’s

sails.

THE SAILS

|

|

|

Fig. 3.3: Leach’s Mill, Wisbech. Ceased milling ca.

1895. |

A windmill’s sails are usually four in

number, but five, six and eight-sailed windmills (fig 3.3) were also

built. More sails generate more power with a smoother torque,

but at greater cost, weight and maintenance.

A windmill’s sails do not rotate in the vertical plane, but are

slightly inclined to it, for it was discovered that a slight

inclination of about 15° increases the wind’s effect (fig. 3.4).

This is due to wind currents near to the ground meeting more

frictional resistance than higher up, to the extent that at a level

of 43 ft above ground-level, wind velocity is some 10 per cent

greater than at 20 ft. To accommodate the tilt of the sails,

the windshaft has also to be inclined at the same angle below the

horizontal, with its rear end held in place by a firmly-embedded

bearing to enable it to rotate while preventing it from sliding

backwards (plate 17;

plate 25).

A further discovery was that sails worked more efficiently if,

rather than being set flat across the sail stock, a slight twist is

applied, this being more accentuated nearest the windshaft (about

18°) lessening towards the tip (about 7°); this twist can be seen in

the sails of Quainton mill (plate 26).

A major problem for the miller was to regulate the speed of rotation

of the sails and thus of the millstones. The optimum sail

speed for a grain mill generally lies in the range 11 to 15

revolutions per minute; speeds much above that run the risk of

over-driving the stones and burning the grain, while even higher

speeds — sometimes referred to as the mill ‘running away’ — could

damage the machinery and, indeed, the mill itself.

Fig. 3.4:

flow of air currents near the ground.

Small differences in sail speed can be adjusted by changing the

amount of grain fed to the millstones or changing the gap between

them, both of which affect the load placed on the sails. But a

large change in wind speed has to be dealt with by altering the sail

area exposed to the wind, either by increasing or reducing it, a

process called reefing (fig. 3.5).

Fig. 3.5:

different degrees of reefing a simple cloth covered sail.

For centuries before the development of more advanced and better

controlled sail systems, sails comprised a lattice framework over

which the sailcloth was spread (plate 10).

Such common sails required two men for reefing, one to climb on the

sweeps to carry out the task and one to control the brake; should

the brake fail during the operation, the man on the sweep was in for

a spectacular ride.

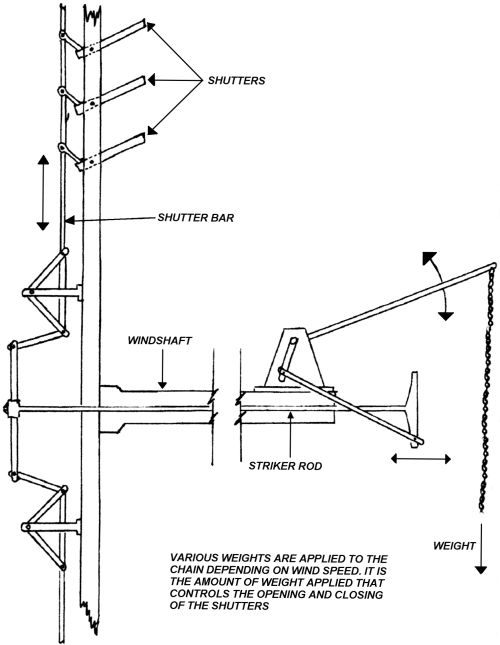

Towards the end of the 18th century, developments in sail design

eased the reefing process. Roller reefing employed banks of

cloth blinds mounted on rollers (comparable to a household roller

blind) that could be adjusted with a manual chain from the ground

without stopping the mill. Other systems replaced the

sailcloth with sets of wooden shutters (comparable to Venetian

blinds) mounted along each sweep. These systems employed some

form of tensioning that caused the shutters to spill the wind

automatically if its force exceeded a set limit. A later

invention, the air brake (fig. 3.6), comprised shutters placed

longitudinally at the tip of each sweep that turned automatically if

the wind exceeded a set strength, thereby disturbing the sail’s

profile and slowing it.

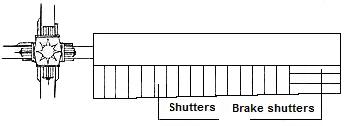

Fig. 3.6:

top, a sail fitted with shutters and air brake.

Bottom, a sail for simple cloth covering.

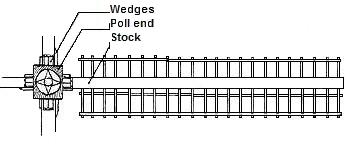

The development of hollow windshafts permitted control rods to be

inserted through their centre (fig. 3.7). This enabled sail

settings to be adjusted from within the mill automatically under the

action of counter-weights.

|

Fig. 3.7: towards

the end of the windmill era, shuttered sails were introduced that

enabled a degree of automatic reefing by applying tension weights to

balance the wind pressure falling on the shutters. The two

forces were balanced through the striker rod (which passes through

the centre of the windshaft), the shutters bars and moveable

linkages/levers. |

While these developments were not without their complexities when

compared to common sails, they reduced manual effort while improving

the windmill’s efficiency as a motive force.

THE MACHINERY

Different hardwoods were used in the construction of milling

machinery. Cogs were often of applewood, hornbeam or beech,

wheels and shafts of oak, whilst the dowels used to join together

wooden parts were of holly. However, from the middle of the

18th century cast-iron parts were used increasingly, although

iron-to-iron gearing was avoided, for it was found that iron-to-wood

gearing ran more quietly and was easier and cheaper to maintain and,

most important, it avoided the risks of sparks causing a dust

explosion. [4] Problems associated

with manufacturing and handling large iron castings were avoided by

the use of small sections bolted together, an example being the

dozen or so sections that make up the 18ft diameter iron rack in the

cap of Wendover mill (plate 24).

Fig. 3.8:

general arrangement of a windmill fitted with a cap and fantail, and

two sets of stones.

In order to rotate the millstones, the (near) horizontal rotation of

the windshaft must first be converted into a vertical rotation.

This is achieved using a form of bevel gearing. The inner end

of the windshaft is fitted with a large toothed wheel, the brake

wheel, the teeth of which mesh with a cog, the wallower, which is

set at an upright angle to it. The brake wheel, when rotated

by the windmill’s sails in the horizontal, causes the wallower to

rotate in the vertical (fig. 3.8).

The wallower is mounted on the upright (or main) shaft, which

transmits its rotary motion downwards through the mill.

Mounted on the base of the upright shaft is another large toothed

wheel, the great spur wheel. This in turn meshes with the cogs

— called stone nuts — that drive the millstones. In this way

the wind’s energy is captured and then put to work to grind grain

and drive other machinery for cleaning, sifting and hoisting grain.

As its name implies, the brake wheel’s other function is to stop the

mill. In fig. 3.8, the brake is the circular shoes that

surround the brake wheel. To stop the mill, a lever is pulled

to tighten the brake-shoes causing them to grip the periphery of the

brake wheel and thus slow the rotating windshaft or clamp it in

place.

THE MILLSTONES

Windmills are generally equipped with several sets of millstones (plate

14). Each set comprises a rotating runner stone and a

stationary bed stone which, depending on their diameter, weigh in

the region of two tons. Different types of stone are used to

grind different types of grain. Stones of grey millstone grit

from Derbyshire are used to grind coarse meal for stock feeding.

The millstones employed to grind wheat for flour are made of French

Burr, a hard silicate found in the Seine valley. Burr stones

are constructed in segments, cemented together and bound with heavy

iron bands.

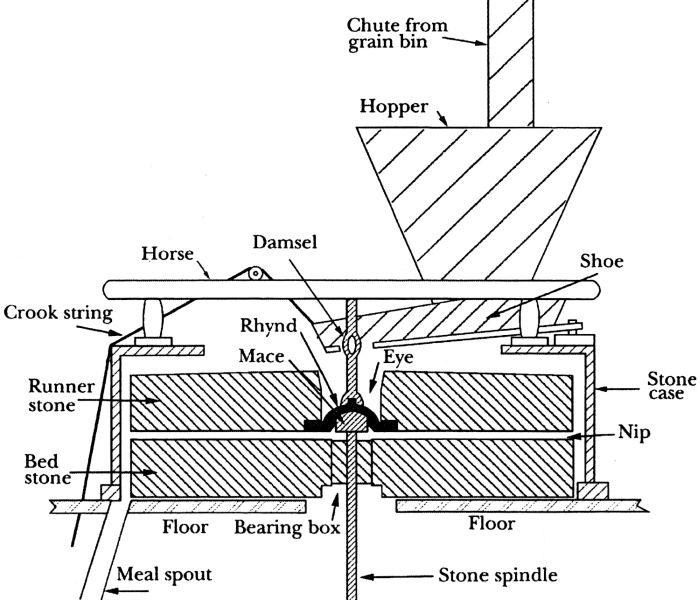

Fig. 3.9:

millstones and their associated equipment.

In operation, the millstones (fig. 3.9) are fed from a hopper, which

trickles grain along a wooden trough — the shoe — into the eye (a

hole through the centre of the runner stone) where it is ground

between runner and bed stones. The shoe is kept in a continual

state of agitation by a rotating crank. Called the damsel, due

to its chattering sound when in operation, it serves to keep the

grain flowing steadily down the shoe into the eye.

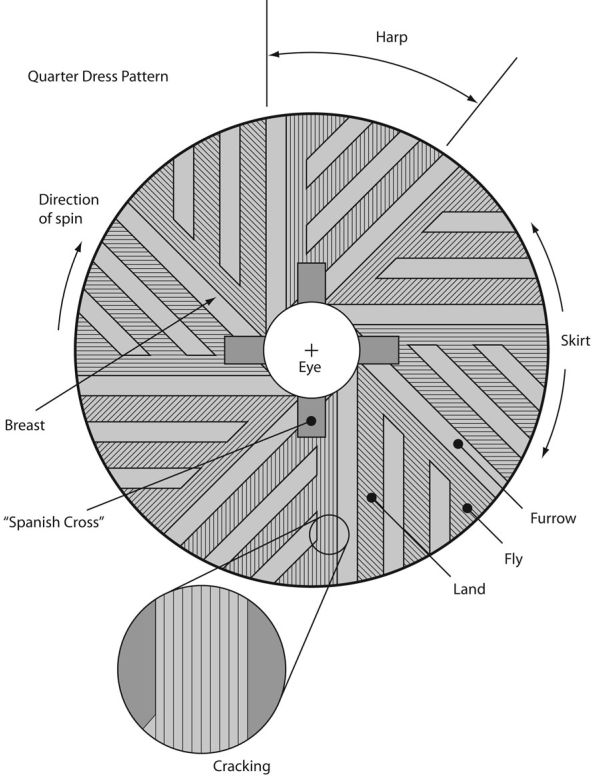

Each stone has a pattern of grooves cut into its surface (fig.

3.10). The grooves act like scissors, cutting the grain as

well as moving it outwards from the centre to the periphery of the

millstones. As the meal emerges from between the stones, it is

swept inside the circular wooden container that encases them — the

tun or stone case — into the top of a chute, or meal-spout, which

funnels it down to the meal floor below where it is bagged.

|

Fig. 3.10:

plan view of a millstone. This is a runner stone;

a bedstone would not have the "Spanish Cross" into which

the supporting millrynd fits. |

In regular use, the grooves in a millstone wear down and need to be

dressed periodically; that is, re-cut to keep their cutting surfaces

sharp. This is a tedious and exacting task, sometimes

performed by the miller but often by an itinerant stone dresser

(fig. 3.11). The work was executed using various tools

including a mill bill, a tempered steel blade clamped in a wooden

handle, rather like a small pickaxe, and used as a chipping tool.

Today, power tools are often used.

|

|

|

Fig. 3.11: a stone dresser using a mill bill. |

Adjusting the gap between the stones — a process called tentering —

is carried out using a system of screws or levers that move the

runner stone up or down. This gap, or nip as millers call it,

helps to determine the fineness of the meal; the smaller the nip,

the finer the meal. Only slight adjustments are required, for

the stones, when grinding, are only about the thickness of a

postcard apart.

Fig. 3.12:

the centrifugal governor.

Tentering can be performed manually, but the centrifugal governor

(fig. 3.12 & plate 2) can perform the

task more efficiently. This ingenious device is driven from

the rotating upright shaft. As the speed of rotation of the

sails — and thus of the shaft and the millstones — increases, a pair

of heavy metal balls linked to the governor’s spindle begin to fly

outwards under the increasing centrifugal force. This causes

their collar to rise up the spindle, and in so doing to move the

levers that adjust the gap between the millstones. An

increased gap results in more grain being fed into the eye of the

millstones, which increases the load on the sails, slowing their

speed of rotation and that of the millstones.

The optimum speed of rotation of a runner stone depends on its

diameter and on the quality of the output required. A rule of

thumb followed by millers was to divide the diameter of the stone

(in inches) into 5,000 for flour and 6,000 for coarser meal.

Thus the optimum speed for a 48 inch runner stone, set to produce

meal, would be 125 rpm — assuming, of course, there was sufficient

wind to drive it at that speed.

THE FANTAIL

Even a small change in wind direction can result in a significant

reduction in the torque the sails generate if they are not

repositioned. In older windmills, ‘winding the mill’ involved

hard manual effort. In the case of a post mill, the entire

superstructure needed to be turned by pushing on a large beam (the

tail post) that protruded from the rear of the mill. In later

smock and tower mills, only the top floor (fig. 3.1) needs to

revolve, but this still required manual effort. The fantail

automates the process by using the wind itself to wind the sails.

Later windmills usually adopted this feature, which could also be

built onto the tail posts of old post mills (plate

31).

A fantail comprises gearing driven by a small set of sails (vanes),

which are aligned at right angles to the main sails and positioned

at the rear of the mill. Its purpose is to rotate the cap

automatically when a change of wind direction occurs, which it

achieves via a system of gears that mesh with a toothed rack around

the inside of the cap (fig. 3.8). When the sails are properly

winded, the vanes of the fantail are at right angles to the wind, so

they derive no thrust from it and do not rotate. But should

the wind change direction, its force then falls on one side or the

other of the fantail, causing its vanes to rotate and drive the

gearing that rotates the cap and winds the sails, a clever feat of

automation.

However, while very useful in normal working conditions, the fantail

provided no guarantee against a mill being tail-winded by a sudden

change in wind direction, as sometimes accompanies a thunderstorm;

thus fantails might be supplemented by a hand crank, an example

being in the cap of Wendover mill (fig.

10.3). And unless the fantail drive could be

disconnected, a further problem for the miller was how to turn the

windmill’s sails off the wind in a sudden squall in order to stop

them. Things were rarely straight-forward in windmilling.

ANCILLARY EQUIPMENT

|

|

|

Fig. 3.13:

principle of the flour dresser. The cylinder is tilted

at an angle. The wholemeal is fed into the upper

end and passes through the machine under gravity, the

bran being ejected at the lower end. |

Because windmills use gravity feed to

clean and grind grain, filter the meal produced and bag the end

product, a sack hoist is an essential piece of equipment if the

drudgery of lifting sacks manually up the mill, on numerous

occasions, is to be avoided. The sack hoist takes the form a

simple rotating chain, driven by an auxiliary shaft which is in turn

geared to the upright shaft (plate 3).

As it rotates, the sack hoist is used to lift the sacks of grain or

meal up through a succession of trapdoors to the bin floor of the

mill.

The auxiliary shaft also powers other windmill machinery. That

used prior to the grain being milled might include a smutter, which

removes the black spots of smut caused by a fungus disease that can

grow on grain if its gets damp; a separator, used to separate grain

from other foreign matter, such as stones, weeds, and sticks; a

scourer, used to separate usable grain from debris such as dirt,

dust, and chaff.

Following milling, a flour dresser (fig. 3.13) is used to sift the

meal into its various grades of fineness. The dresser consists

of a cylindrical drum, covered in wire mesh of increasing grades of

fineness, and set at an angle. Inside the drum revolves a set

of brushes. Meal, fed into the upper end of the cylinder is

rubbed against the mesh screens by the brushes as it falls through

the cylinder under gravity. The finest meal, white flour, can

pass through the finest mesh screen; next comes semolina flour,

which passes through the next grade of mesh, leaving the coarsest

product, bran. Each grade is ejected into canvas chutes which

feed sacks on the meal floor below.

The mill might also drive an oat crusher, used to crush oats for

animal feed.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX

THE ROLLER MILL

Although the subject of this book is windmills, some mention should

be made of the technology that in the latter part of the 19th

century was to sweep away both wind and water mills so rapidly.

The steam engine was the first major advance. The first

steam-powered mill, Albion Mill, was established in 1786 by Matthew

Boulton and James Watt. It employed a Watt steam engine of 150

hp to drive 20 pairs of millstones, and was capable of grinding 10

bushels of wheat per hour, all day and regardless of wind strength.

Albion Mill was the industrial wonder of the age, but in 1791 it

burned down. The cause was never discovered, but it was widely

believed to be an act of arson by local millers and millworkers who

believed their livelihood was threatened by the new technology.

Rotating millstones, sometimes steam-driven, continued to be used

for grain milling until the late 19th century, when roller mills — a

Swiss invention — appeared, the first being built in Hungary in

1874. Edward Mead (Chapter VII.)

is believed to have installed the U.K.’s first roller mill at

Chelsea in 1881. The combination of steam power and the roller

milling process led directly to the flour mills of today.

|

|

|

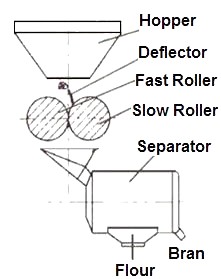

Fig. 3.14:

the principle of the roller mill. In practice, the

meal passes through several stages of roller milling to

produce fine white flour. |

Roller milling (fig. 3.14) crushes the

grain, not between revolving millstones, but between a series of

fluted steel rollers of about 12 inches in diameter. The

rollers are set with a specified gap between them and spin towards

each other at high, but at different, speeds; the surface of each

roller is also grooved with a different pattern.

In a modern flour mill, before milling commences, the grain is

cleaned of any extraneous matter using a variety of techniques

including sifters and magnets (to remove metallic particles).

It is then conditioned to ensure uniform moisture content and

blended with other wheats to provide a mix capable of producing

flour of the required character. Then, using a reduction

process, the grain is crushed by a succession of rollers, the fine

flour particles being sifted out at each pass of the rollers while

the residue (bran) is sent on to the next set of rollers in a

repetitive manner. Thus, roller milling is a series of

crushing and sifting operations, ideally suited for making clean

white flour.

Roller mills offer several other advantages over traditional milling

methods. They eliminate the cost of dressing millstones and

enable the production of a larger amount of better-grade flour from

a given amount of wheat, quicker and to a consistent standard.

Rollers are also superior for milling the harder wheats used for

bread by reducing the wheat kernel slowly into flour fragments to

separate out the bran.

Roller milling made possible the construction of larger, more

efficient grain mills, hastening the abandonment of the small

country wind and water mills, and of stone grinding. Indeed,

so successful were the roller mills that within 30 years of their

introduction into Britain in 1881, more than three-quarters of the

wind and water mills that had served for centuries so faithfully, if

erratically, had been demolished or abandoned. This is what

Edward Bradfield, an old miller who was writing in 1920, had to say

about this milling revolution . . . .

“Then came the changes. ‘High grinding,’ ‘gradual reduction’ and

the ‘roller system’, one after the other, came to revolutionize the

trade. The flour was greatly improved by the new methods and

the trade of the stone millers was decimated. The new methods

allowed the brittle stony wheats then coming into fame to be made

into excellent flour which the stone millers could not equal.

Yet many of them, who clung to the traditional system which had

brought them fame, wealth and honour, made heroic efforts to stay

the onslaught, but failed.”

However, the roller mill revolution brought with it a drawback.

The friction of the rollers caused the meal to become hot, which led

to some nutrients in the flour being damaged. This was not

realized at a time when essential dietary needs were little

understood.

Today, the

‘Bread and Flour Regulations’ govern the use of

additives as well as requiring the addition of certain nutrients to

ensure that a wholesome product emerges from the flour mill.

This from the Federation of Bakers . . . . .

“The Bread and Flour Regulations require that flour should

contain not less than 0.24mg. thiamin (vitamin B1), 1.60mg.

nicotinic acid and 1.65mg. of iron per 100g. of flour. These

amounts are found naturally in wholemeal flour. White and

brown flours must be fortified to restore their nutritional value to

the required level. In addition calcium carbonate, at a level

of not less than 235mg. and not more than 390mg. per 100g. of flour,

is added to all flours except wholemeal and certain self-raising

varieties. This ensures the high nutritional value of all

bread, whether it is white, brown or wholemeal.” |