|

ROADS, AND THOSE IN TRING.

HIGHWAYS AND

BYWAYS.

|

“During the engagement of

Mr. J. E. Maynard as Surveyor of the roads in this county, he

has rendered great relief to different parishes employing the

superfluous poor collecting and preparing materials, and

introducing an advantageous plan for improving the highways.

In the Parish of Tring, Mr. Maynard in the space of nine months,

expended upwards of three hundred pounds assisting the poor who

otherwise must have been supported by parish relief.”

From the Tring Vestry Minutes

for 1822.

“It was ascertained by

Mr. Rogers one of the Guardians of the Poor that two of the men employed

on the road in Akeman Street,

‘Oakley

and Nash’,

were neglecting their work and sitting by the road side asleep.

He therefore took up their tools and discharged them. They both

said they

‘did

not care being turned off their work.’”

Tring Vestry Minutes, 22nd

April 1828. |

Ancient Roads.

The Tring Gap ― a lowering in the Chiltern Hills in which the town is

sited ― has provided the traveller and his animals with a thoroughfare

over the ridge since time immemorial. Two ancient highways, the

(Upper) Icknield Way and Akeman Street, crossed each other

in or near the modern town, although their point of intersection is

unclear.

The earliest written reference to the Icknield Way [1]

is contained in Anglo-Saxon charters of AD 903, [2]

but its true age remains something of a mystery. Thought to have

been one of a few long-distance trackways ― in fact a series of tracks ―

that existed before the Roman occupation, it followed the grass chalk

downland of the Chilterns, some historians claiming that it linked

The Wash in East Anglia with Wiltshire. However, in addition

to a lack of material evidence of its age, its route would have cut

across the local territories defined by regularly spaced hill forts and

dykes running perpendicular to the Chiltern escarpment. Before the

arrival of any strong central authority, movements along it in ancient

times would surely have involved travellers in numerous awkward local

negotiations, making its use as a long-distance trade route appear

doubtful.

Between Lewknor and Ivinghoe the track diverges into two parallel

courses, known as the ‘Lower’ and the ‘Upper’ Icknield Way.

Here a further uncertainty enters the debate:

|

“The Upper Icknield Way has all the characteristics of a

trackway, following the steep escarpment of the Chiltern range,

but the Lower Way is here peculiar in following a series of true

alignments on the flat land in a position unlikely for a

trackway and quite typical of a Roman road . . . . There can be

little doubt that this part of the Icknield Way is a true Roman

road.”

Roman Roads in Britain,

I. D. Margary (1955). |

Modern scholarship casts doubt on a ‘Roman’ Icknield Way due to

the scantiness of archaeological finds and proof of Roman road

construction. Perhaps for this reason ― and unlike nearby

Akeman Street ― its course is not marked on Ordnance Survey maps

(including the Ordnance Survey’s map ‘Roman Britain’).

Nevertheless, archaeologists working during the 1950s mapped what they

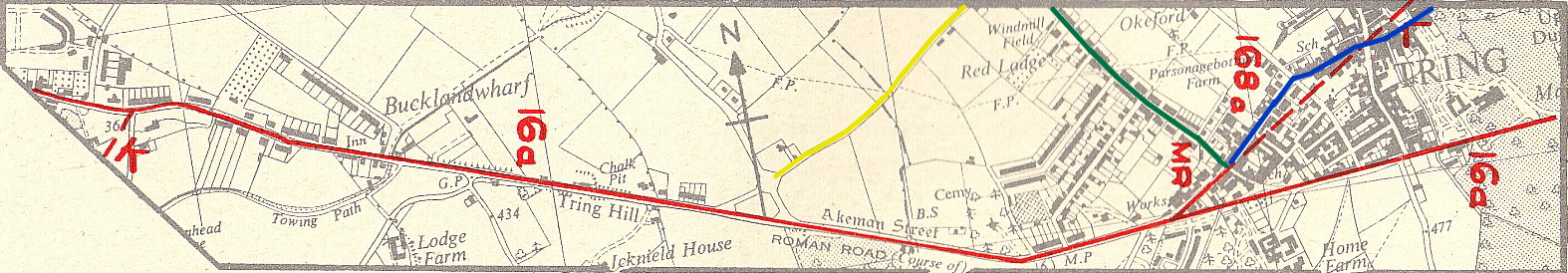

believed to be the course of the ‘Roman’ Icknield Way. That

part of their map reproduced below shows the section of the Way (in red)

near Marshcroft Lane (in yellow) in Tring; to the left of the map, the

Way crosses Grove Road (in green), passes through the modern Chiltern

housing estate (yet to be built in the 1950s) and along Mortimer Hill

before entering the town centre to the north of the Robin Hood

public house. |

|

Thus, the age and line of this ancient road in this

locality remains a matter of conjecture, while its Romanization remains

a mere possibility (but more under Akeman Street below).

What is known is that by the Medieval period the Icknield Way

is referred to as one of the ‘Four Highways’ of the Kingdom, although

even here there is possible confusion between Icknield Way and

the Roman Ryknild Street. [3]

Much more is known about Akeman Street, [4]

sections of which are located and marked ‘Akeman Street, ROMAN ROAD’ on

Ordnance Survey maps of the Tring locality ― the road’s name,

incidentally, is not of Roman origin, but dates from the early Middle

Ages. Originally a late-Iron Age track, the Romans adopted

sections of it to form a road from Verulanium (St. Albans) to their

garrison towns of Alchester near Bicester and onwards to Cirencester.

Evidence for its construction and age is based on archaeological

excavations, such as that recently conducted in the parish of

Quarrendon, Bucks.:

|

“Akeman Street was sectioned at Billingsfield, Quarrendon,

revealing a gravel surface up to 6.6m wide, with flanking

ditches. The gravel surface had been constructed on a

raised bank of three make-up deposits, with a buried soil

possibly surviving beneath. The road seems to have been

constructed at an early stage in the Roman occupation, as two

cremation urns of mid 1st-century date were inserted into pits

cutting the edge of the outer ditch. Pottery from the

fills of the flanking ditches was 1st to 4th century in date

(Cox 1997). Related quarry pits and traces of make up

layers of Akeman Street were also encountered at the Aston

Clinton bypass.”

Roman Buckinghamshire,

R J Zeepvat & D Radford (2007). |

In 2011, Archaeologists undertaking excavations in advance of building

development at nearby Berryfields, Aylesbury, also uncovered the road’s

metalled surface and two pairs of flanking drainage ditches, the

characteristic profile of a Roman road.

|

|

|

Roman coin

found at Cow Roast. |

Nearer at hand, behind the Cow Roast Inn

on the London Road, lie the remains of a Roman settlement that extended

to the hillside on the opposite side of the main road (A4251), beyond

today’s canal marina. Over the years this site has yielded many

valuable finds. As early as 1811, the

Gentleman’s Magazine reported the discovery of coins and a gold

ring, and other items such as military artefacts, pottery and jewellery

have been found over the years. Later excavations uncovered 14

well shafts, which together with other finds suggest that the site was

used for the production of iron. In addition to Roman remains,

there is evidence on the site of an earlier Iron Age settlement.

More recently another Roman site was discovered to the rear of the

now-demolished Old Grey Mare public house at Northchurch, but

pressures for new building prevented extensive excavations.

Work under the sponsorship of Dacorum Heritage Trust is still being

carried out to establish the exact line of the Roman road, while

evidence of Roman construction suggests a second road crossing north to

south in the Cow Roast area, presumably extending between Aldbury and

Wigginton.

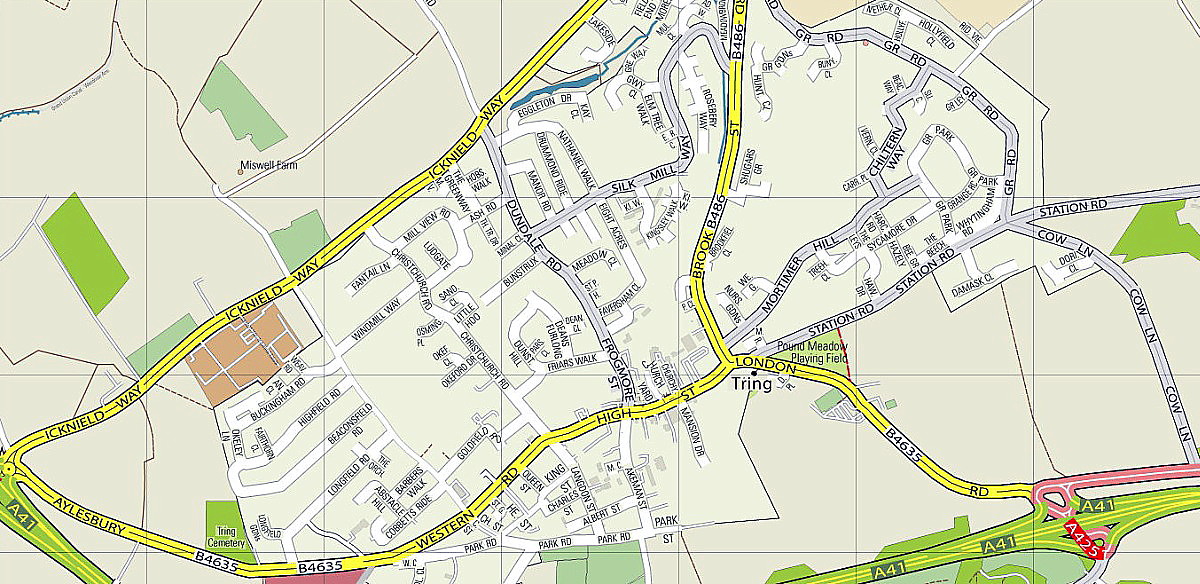

That Akeman Street continued westwards to Tring was

established by

The Viatores, a group of researchers working during the

1950s. [5] They discovered that at the lodge entrance

to Pendley Manor, Akeman Street turns abruptly to west (shown on the

right of the map below) and then continues straight as far as Tring

cemetery. Its course through Tring Park is marked by part of an

agger, 45 feet wide by 1 foot high, [6] the excavation

of which revealed flint and gravel bound with lime mortar (more sections

of agger together with flint metalling were discovered in the vicinity

of New Ground). |

|

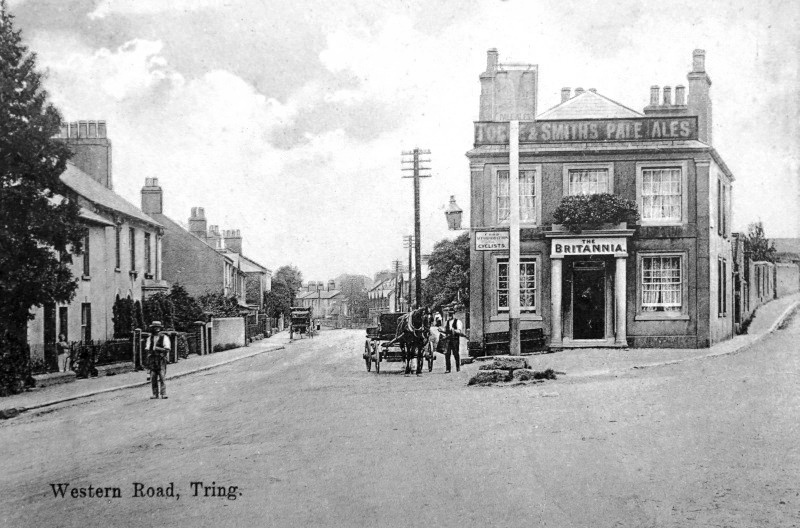

At the former Britannia Inn (now a private house at the

junction of Park Road and Western Road),

The Viatores conjectured that Akeman Street formed a

junction with the ‘Roman’ Icknield Way, the two then following a

common path to Aston Clinton. At Tring cemetery, the road turns to

the north-west (point AA above) before commencing the long alignment

across the Vale of Aylesbury (below). |

|

These maps were drawn in

the 1950s, since when Tring has become more built up and the new A41 has

appeared.

On the map above, the modern Icknield Way is shown above in

yellow, Miswell Lane in green, and Tring High Street in blue. The

certain course of Akeman Street appears as a solid red

line, while the presumed course of the ‘Roman’ Icknield Way

appears as a broken red line passing through Tring town centre.

Having shared a common path down Tring Hill,

The Viatores identified the junction of Stablebridge and

London roads (point K above) as that at which Akeman

Street and the ‘Roman’

Icknield Way diverged. During 2014, Archaeologists from the

University of Leicester excavated a site at this location prior to

housing development, and found evidence of both Iron Age and Roman

settlement. Their provisional dating suggests that the site in its

final form dates to the 1st or 2nd century AD, with activity in the area

continuing as late as the mid-3rd century AD.

The site was also found to be bisected in a south-west to north-east

direction by a wide (13m) trackway, the edges of which were defined by

long, straight ditches typical of a Roman road. Narrow ‘wheel

ruts’ were identified along parts of the carriageway, some of which had

been infilled with packed flint, possibly evidence of repairs, whilst

other broader spreads of flint could be the remains of metalling.

When viewed on maps of the wider area, the alignment of the trackway

matches the projected course of the Lower Icknield Way,

which might have its origins in the Iron Age or earlier. This

evidence appears to support the route of the ‘Roman’ Icknield Way

as conjectured by

The Viatores during the 1950s.

Market Street (now

the High Street).

“The street running through the centre of the Town, hitherto

known as Market Street, is changed, and will be called in future High

Street. It appears by an old record dated July 3rd 1711, that the

Street was then called High Street, so it is only reverting to its old

name.”

From the

Tring Vestry Minutes for 1833.

The original line of the approach to Tring, from both easterly and

westerly directions, as well as the actual route through the town, saw

many changes over the centuries. Consequently, it is confusing and

difficult to follow, especially as some traces of the old sections of

road have disappeared.

Tring High Street looking towards the old

Rose & Crown Hotel (on the right). Note

the condition of the

pre-tarmac road surface ― no wonder the road needed to be watered in

summer to suppress the dust.

A glance at a modern-day Ordnance Survey map shows that the most direct

route from Cow Roast to Tring follows the line of the age-old livestock

droving road to and from London, along the present A4251, until London

Lodge (the former Rothschild gatehouse) is reached. At this point

the old road continued straight through Tring Park, passing immediately

to the south the Mansion to emerge in Park Street. It then

continued along Park Road to form a junction with the present Aylesbury

Road at the old Britannia public house ― in Victorian times this

junction was known as ‘Bottle Cross’. [8]

The ‘Bottle Cross’

junction. The Britannia Inn is left of centre, the pub on the

right is

the

Bricklayers Arms

(note the horse trough).

The entrance to Duckmore Lane is on the extreme right.

The road then followed its present course past Tring Cemetery and

straight on towards Aylesbury and Fleet Marston (once a Roman road

junction).

The year 1711 saw a change to this age-old route, one that brought

increased prosperity to the town up until the end of World War II, when

the tremendous growth of road transport rendered the narrowness of the

High Street inconvenient and unsafe for large volumes of traffic.

In 1702, the Tring Park estate was acquired by Sir William Gore,

one-time Lord Mayor of London and wealthy banker. On his death,

the estate was inherited by his eldest son, William junior, who

petitioned that the main road be moved from the south to the north side

of his mansion because, it is believed, he disliked traffic passing his

dining room windows. Given the influence of the gentry in those

times it was probably a mere formality that his application for the

change was approved:

|

“At the house of William Axtell, Rose & Crown, Tring, an

inquisition was held relating to the enclosure by William Gore,

esquire of Tring, of part of the highway from Berkhamsted to

Aylesbury known as Pestle Ditch Way, which lies on the

south part of his garden from Dunsley Lane to a place called

Maidenhead. [9]

In substitution he will provide a road from Dunsley Lane across

Tring Market Street and New Lane to a place in his land called

Gore Gap.” [10]

Tring Vestry Minutes

11th January 1710. |

The inquisition was conducted before the Sheriff for Hertford, with

seven esquires, three gentlemen, and eight commoners forming the jury.

The verdict was, unsurprisingly, that there would be no damage to the

Queen or to others by the diversion of the highway for a distance of 92

perches (506 yards) [11].

This new route of the main highway as it reached Tring from the

Berkhamsted direction, still did not follow a line that would be

recognisable today. At London Lodge, it made its way to the south

of Lower Dunsley ― which was located near the site of today’s Dunsley

Place

(‘Donlee’ on the map below), but then a hamlet in its own right ― where

it wound its way between the houses, canvas factory and brewery to

emerge opposite the Robin Hood public house. From there on the

route corresponded with the present High Street until the ‘Gore Gap’ was

reached (in the map below, located at the road intersection above the

‘G’ of Tring), where the road turned south then immediately west along

Park Road, eventually to join the Aylesbury Road at the Bottle Cross

junction (in the map below, to the left of the ‘T’ of Tring).

|

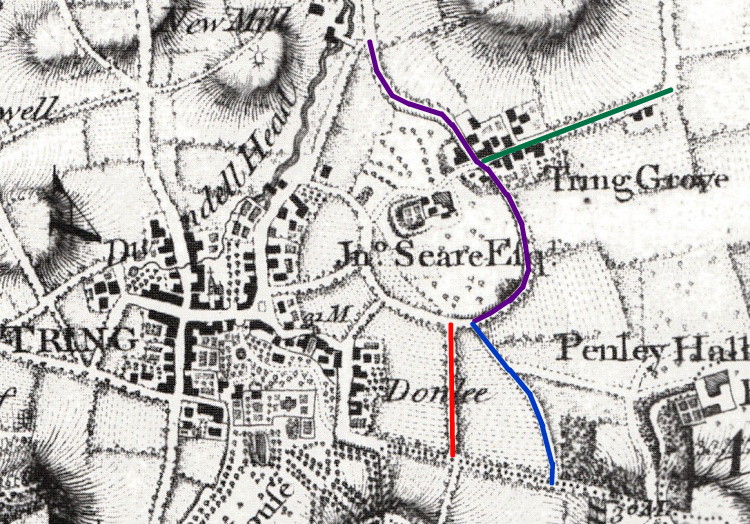

Dury and Andrews’

map of Tring, c.1766. This map is a schematic illustration rather than one

drawn to scale.

Key: London Road ― red; Miswell Lane ― green; Frogmore Street/Akeman

Street ― blue; Brook Street ― purple; Park Road/Street ― yellow.

The hamlet of ‘Donlee’ (map centre) ― approx. today’s Dunsley Place ― was

demolished by Lord Rothschild in the 1870s.

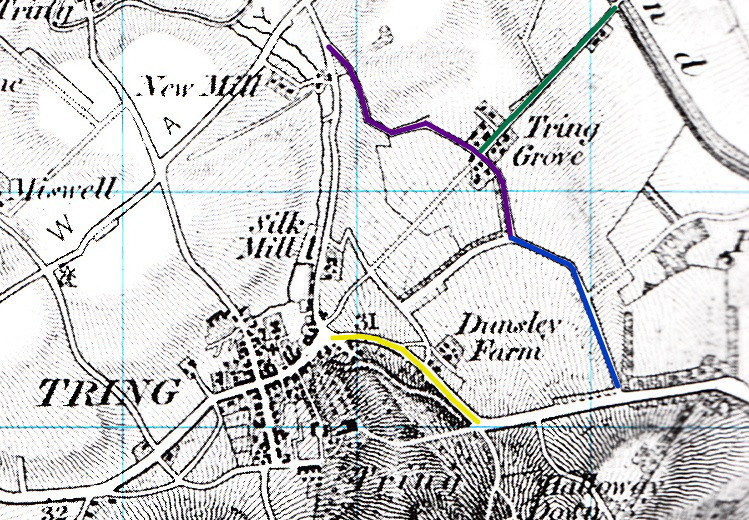

Much the same area mapped by Andrew Bryant

c.1822. Western Road is shown, but no direct route from the town to the site of

its future railway station.

The feint double dotted lines around the

hamlet of Dunsley suggests the bypass section of the turnpike is under

construction, which ties in with what is known at this time.

Tring town centre today. Many new roads and houses

were built in the post WWII period.

|

At some time during the early 1820’s, a new section of road was created

between London Lodge and Dunsley, the work being undertaken for the

Sparrows Herne Turnpike Trust by James Bull of Tring. [12]

This necessitated some road widening, the demolition of dwellings and

payment of compensation. William Kay, the Lord of the Manor, was

awarded £248.15s.0d. compared with the £4.17s.0d. to the four cottagers

who were obliged to quit their homes. The main road now bypassed

Dunsley.

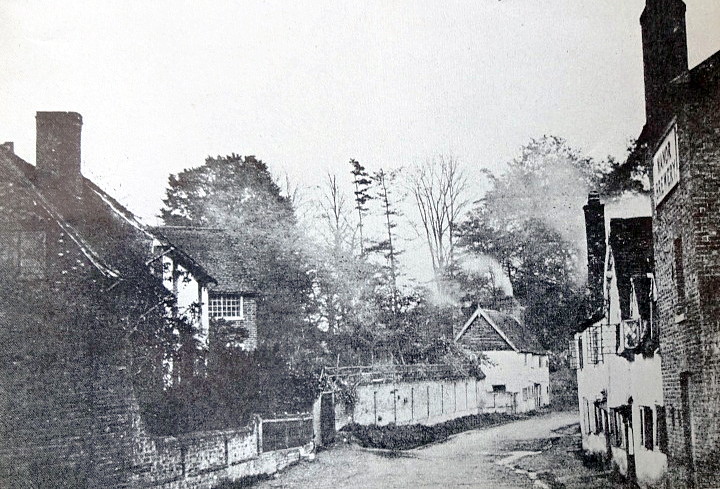

Above: a very early view (c. 1870s) of Tring

from the top of Station Road. The Manor Brewery at Dunsley

is on the left, its chimney shown ―

presumably it tapped one of Tring’s subterranean streams for its water.

Below: the only known view of the hamlet of

Dunsley. Manor Brewery is on the right.

Near the entrance to today’s Dunsley Place there survives a Grade

II listed monument of 1826, a white cast-iron milepost showing the

distance to London and nearby places along the road. The Sparrows

Herne Minute Book records that the Reverend Lacy (vicar of Tring

and one of the Trustees) designed the lettering and that an estimate was

requested from Mr J Dell, ironfounder of Dudswell, to form and cast the

plate.

Sparrows Herne cast-iron

milepost c.1826.

Two original Sparrows Herne waymarkers still exist, at Bushey and at

Berkhamsted, and a replica can be seen in Tring mounted against the wall

of the Memorial Gardens, almost opposite the Robin Hood, where the

original was sited until 1991 when it was inadvertently lost during some

drainage work.

Sparrows Herne turnpike

waymarker (on the right) at Tring.

From the following entries in Tring Vestry Minutes and the

Bucks Herald it seems that the old road through Dunsley hamlet was

not closed until 1883:

|

1883. The old road at a point on the south side of the High

Street, adjoining the Manor Brewery, and the Canvas Factory, is

to be closed. This refers to Lower Dunsley.

1883, 25th August ― Notice has been issued notifying the

intended closing in the usual way of the now useless road at the

southern end of Tring . . . . |

Subsequently, Lord Rothschild decided to incorporate the whole area into

his private gardens, although it was some years before the Lower Dunsley

buildings were demolished:

|

DEMOLITION OF OLD BUILDINGS. ― The

Manor Brewery and houses at the bottom of High-street, on

the Station-road entrance to the town, which have been

unoccupied for some time past, are now pulled down. It is

almost needless to say that they will not be rebuilt, as

they are on the confines of Tring Park.

Bucks Herald, 11th January

1896. |

Western Road.

In 1822, the turnpike trust drove a new section of road straight through

the grassland between the Gore Gap and Bottle Cross:

|

“The trustees of the Sparrows Herne Turnpike are making most

excellent improvement in the road at the Aylesbury entrance of

the town of Tring, by cutting an entirely new line through the

inclosures, to avoid the present dangerous turn of hill.”

Morning Post 7th

February 1822. |

At some date between 1860 and 1870 this stretch of road came to be known

as ‘Western Road’, a name originally referring to the section between

Akeman Street and Langdon Street, later to become the (Upper) High

Street. Before the construction of the ‘new’ Western Road, the

age-old approach into the town centre from the westerly direction was as

equally convoluted as that from the east. In addition to the Park

Road route, at the Bottle Cross junction a road then existed that veered

north, then east, winding up Abstacle Hill, crossing Miswell Lane to

join a track (now Christchurch Road) where it turned south to connect

with the main road at the Gore Gap.

Following the 1822 alteration, the route of the highway through the town

was complete and remains that with which we are familiar today.

However, the steepness and narrowness of the High Street continued to be

far from ideal for use by Royal Mail stagecoaches and other horse-drawn

traffic.

Beggar Bush Hill (now

Tring Hill)

[13]

First suggested in 1810 and again in 1816, it was not until around 1824

that alterations to the western approach to the town in the Tring Hill

area were undertaken by the Sparrows Herne Turnpike Trust. In

order to reduce the gradient a considerable amount of excavation took

place to reveal the chalk cutting seen today in the vicinity of the

Crow’s Nest motel.

The following advertisement appeared on 22nd November 1823 in the

Windsor & Eton Express (later the Bucks Gazette):

|

SPARROW’S HERNE TURNPIKE

To Road Contractors, etc.

Such Persons as are willing to CONTRACT for the necessary works

in CUTTING THROUGH and LOWERING BEGGAR BUSH HILL, on the

Sparrow’s Herne Turnpike Road, between Tring and Aston Clinton,

are desired to send Tenders in Writing to the Office of Messrs.

Grover and Smith, Solicitors, at Hemel Hempstead, Herts, on or

before the 6th Day of December next, to be submitted to the

Trustees at a MEETING on the 8th of DECEMBER. A Plan and

Specifications of the works may be seen at the Rose & Crown,

Tring, the Bell, Aston Clinton, at the Office of Messrs. Grover

and Smith, and at Mr Creed’s, Surveyor, Hemel Hempstead. |

Various tenders were laid before the Trustees on 8th December 1823, who

decided to award the construction contract to James Bull of Tring and

Thomas Morris of Aston Clinton, the former being the preferred choice of

the Trust’s Surveyor, the famous engineer James (later Sir James)

McAdam. Three days later, a Bond for the Performance of Covenants,

and an Agreement [14] were drawn up and signed by all

parties. |

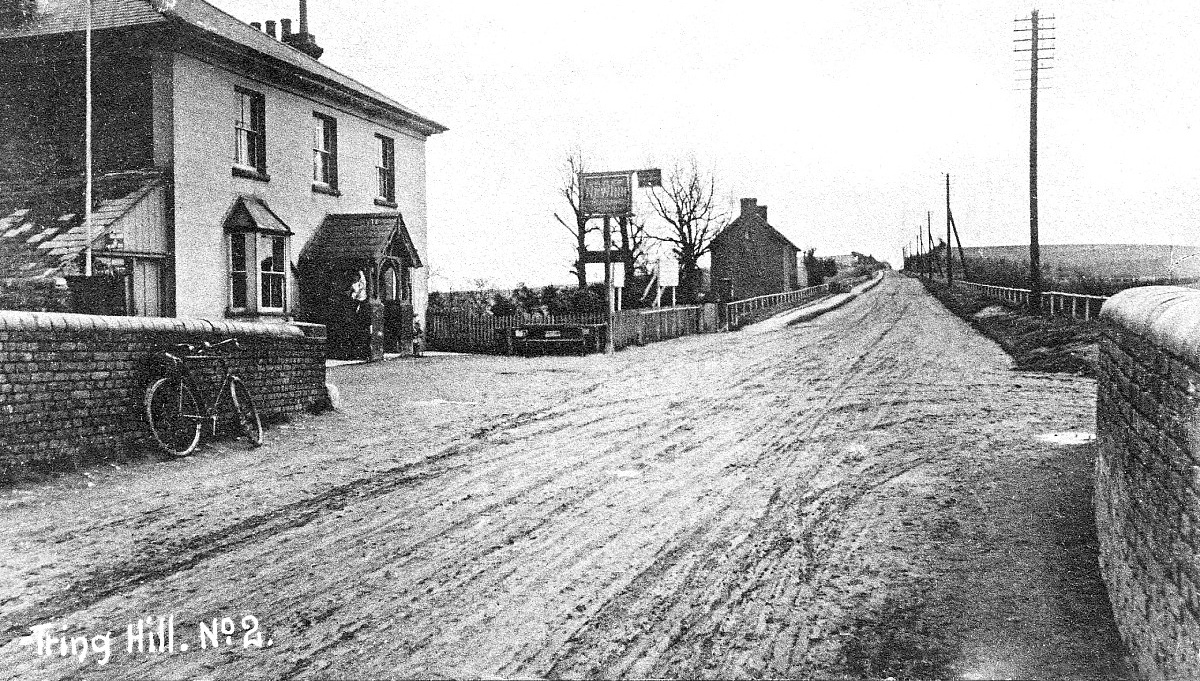

This view of Beggar Bush Hill ― now Tring Hill ―

clearly shows the cutting driven through the

ridge in 1824,

lowering it by 36 feet, and the even gradient that resulted.

Note the condition of the pre-tarmac road surface! The public

house on the left, the New Inn, is now business premises.

|

In addition to the excavation work and the provision of a temporary

roadway whilst the work was in progress, the contract included the

necessary embanking, fencing, quicking (i.e. hedging), rails and

culverts, and a payment by the contractors of £500 to be laid down as a

sign of ‘good intent’. The work was to be complete by 1st December

1824. Pauper labour was provided by the overseers of Tring

Workhouse [15] and the total cost amounted to £2,416

1s. 3d.

However good the surface was then considered, a letter [16]

to the Trustees from farmer John Edmonds of Buckland Wharf written in

May 1825 showed little appreciation, for he complained that the state of

the hill nearly caused him an accident with a load of hay on board ― “.

. . . it was a good road before the Hill was took down . . . .”

Some 40 years later the Bucks Herald was grousing:

|

1867, January. TRING. “We have many complaints made to us of

the state of the turnpike road between this town and Aylesbury.

The hill at Beggar’s Bush was almost impassable before the late

frost. Surely the Trustees will see to it?” |

|

|

|

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

cafe with Mr. Pratt, its proprietor,

standing proudly

in the doorway. |

A curiosity that once stood on Tring Hill is remembered by some of the

Town’s older folk. Sometime before WWI, Mr and Mrs Dodd of Henry

Street set up a stall halfway up the northern side of Tring Hill, from

which they served light refreshments to passers-by. Around 1914,

Mr and Mrs Pratt obtained permission to place two disused railway

carriages on the same site, one being used as a café and the other as

living accommodation; a disused chalk pit on the opposite side of the

road served as a pull-in for lorries and cars. They named their

pride and joy ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’.

During WWII the café became a venue for dinners and wedding

receptions, and due to its comparatively isolated position was also the

target for a number of break-ins, reports of which appear in the local

newspapers of the time. The structure remained until sometime in

the 1960s, Bill Pratt dying in 1974. This poor reproduction

photograph shows him standing in the doorway.

Station Road.

Station Road is not one of the town’s old roads. Built in 1838, it

provided a direct link between the town and its distant station using

donated land and funds raised by private subscription. Prior to

its construction, the journey from Tring to Pendley and Aldbury followed

a tortuous route, which local historian Arthur MacDonald described in

his notes on the subject (c.1890):

|

“At the east end of

the town important alterations were necessitated by the

construction of the railway, and station in 1838. The

traveller by road from Tring to Aldbury before that date

proceeded up the London Road to Dunsley, turned back across the

3-cornered meadow, following the hedge next the present cricket

ground, to the point where The Laurels now stands, and which was

then the corner of Grove Shrubbery, the latter extending right

round to the fir tree near the recreation ground. Skirting

the shrubbery, as far as Grove Lane, our traveller would then

turn up Cow Lane for a little distance, and strike across what

is now Pendley Park, between the Rookery and a small spinney,

emerging some little distance short of Pendley canal bridge,

this latter part being the ‘Aldbury Road’ mentioned in the

Inclosure Award.” |

Following the railway’s arrival, it soon became apparent that the

popularity of this new form of transport necessitated better

communication between the town and its station:

|

“A meeting of the

Parishioners was held to consider the proposed diversion of the

highway from the Town to Pendley. The inhabitants gave

their consent to the proposed diversion. The consent of

the inhabitants was also given to the stopping of the footpath

leading to Pendley across Dunsley Farm to the swing gate and

also to the footpath across Pendley Park as far as the path is

in the Parish of Tring. The above consents were

conditional on the part of Thos. Butcher Jr. & John Brown on the

understanding that the ratepayers were to be called upon to pay

£300 towards the execution of the New Road and the payments were

to be distributed over 6 years.”

Tring

Vestry Minutes 17th October 1837.

“The inhabitants of Tring have held a meeting at which it was

agreed to form a new road from the town to the station.

Mr. Kay and Captain Harcourt having given the land for that

purpose, and the needed funds raised, buildings are already in

progress, and the inhabitants are making every exertion to

accommodate the public that every day throng this beautiful

neighbourhood, which, from the variety of hill and dale, wood

and water, combined with the extensive views it commands, is

likely to become a place of importance.”

The Bucks Gazette,

28th October 1837.

“The new highway from Tring to Pendley, to be known as the

Station Road, is completed, and in good condition.”

Tring

Vestry Minutes, September 1838. |

In his notes on the Town’s history, Arthur MacDonald leaves a brief

mention of Station Road’s builders:

|

“Bank Alley

[off Tring High Street] (now

occupied by Mr William Johnson, butcher) was formerly the

emporium of Mr Bull, saddler, a leading man in the place and

very wise in road making. He superintended the formation

of the

cutting embankment at Beggar Bush Hill on the

Aylesbury Road, also the making of the new Station Road in 1838,

when he and Mr William Brown were Highway Surveyors. He

held the post of Parish Constable at the same time, with great

effect upon unruly railway navvies.” |

While one might argue that Tring never became the place of importance

envisaged by the Bucks Gazette, Station Road is, nevertheless, an

important highway carrying a high volume of traffic during the commuting

periods to and from the Town and its increasingly built-up surrounding

area.

Other roads

leading from the main highway.

Sunken roads.

From the earliest times until well into the 20th century, the principal

pursuit in this locality was agriculture. Originally, the land

would have been covered with woods and open rough scrub that people used

to graze their cattle, sheep, pigs and geese; this came to be known as

common land, or simply as the ‘common’ and the right to its use was

guarded jealously by the local parishioners:

|

“At a Publick Vestry it was agreed that whereas the Scrubs &

Heath upon Tring Common have been unlawfully cut by persons not

inhabitants of this Parish to the great detriment of the Poor

and the Parish in general. Also several persons have made

a common practice to take up the sheep dung from the Common to

the great damage thereof. Now to prevent these practices

and that there may not be any further incroachments We do hereby

agree that John Geary shall be appointed a keeper of the Common

to prevent any person not inhabitants from cutting the scrub,

gathering the dung and also to impound the cattle of any person

which shall unlawfully depasture the Common.”

Tring Vestry Minutes, 4th May 1773.

At the Vestry held by adjournment to consider the best

method to proceed to prevent the Parishoners of Wigginton

from trespassing upon the

[Tring]

Common. It is ordered that Sanuel Herbert Attorney

shall as soon as possible search all the Ancient Records

belonging to this Parish and enquire of and find out such

ancient people as formerly belonged to this Parish and get

what light may be obtained in regard to the

[Tring]

Common and when he has obtained the same lay it before the

whole Vestry to consider what steps shall be taken.”

Tring Vestry Minutes, 2nd July 1773. |

Livestock were put out each day, often supervised by the very young or

infirm, and each night returned to the farm. The farm needed to

have direct and convenient access to the common, and tracks from farm to

common eventually became worn and sunken through constant use, sometimes

further sunken over the years by the action of torrents of rainwater

sweeping down them. Many of these tracks exist today as ‘sunken

roads’, also known as ‘holloways’, particularly in areas of soft chalky

ground into which tracks are easily worn. They are characterised

by high embankments on each side, sometimes topped with hedges and trees

that can give the traveller the impression of passing through a tunnel.

There are a number of sunken roads in the Tring locality, although long

out of use for their original purpose. Some, such as that from

Icknield Way to Drayton Beauchamp and that from Tring to Hastoe, have

been given a metalled surface and made over to motor traffic.

Others, which no longer serve any socio-economic purposes, such as Leafy

Lane between West Leith and Hastoe, have become footpaths/bridle ways

for leisure use. Their history goes back to Saxon times, when

arable land in the vale of Aylesbury was considered too valuable to use

for grazing, so during the summer months the communities in the

localities of what today we know as Buckland, Drayton Beauchamp,

Wilstone and Marsworth drove their animals up into the hills in the

vicinities of today’s St Leonards, Cholesbury and Hawridge to graze on

the scrubland. Over time, as centralised administration became

established, elongated parishes came to be established in which

villages/hamlets located on the plain had a counterpart several miles

away in the hills ― perhaps the most obvious example on today’s map is

the village of Buckland in Aylesbury Vale, the grazing land for which,

Buckland Common, is located on the ridge of the Chilterns some 5 miles

to the south-east. A number of these elongated parishes remain as

historical curiosities, several miles long but often no more than a

half-mile wide, together with traces of their sunken roads ― some

metalled others footpaths ― that linked them with their former summer

grazing. |

|

|

|

|

Sunken roads (Holloways) near Tring. |

|

Bottom Road (metalled) near Dancersend. |

Footpath through Pavis Wood, Hastoe. |

|

Local roads.

Other traffic by foot or by horseback was mostly within the immediate

area, between farms and nearby hamlets, and to any local town, such as

Tring, where the church [17] and market would have

been the main destinations:

“The market is held on Fridays according to a

charter of King Charles II, who decreed that straw plait should be sold

in the mornings and corn after mid-day. A great deal of business used to

be transacted at the markets, but practically no straw work is sold now

except a little fancy plait, and the corn market has dwindled to three

or four purchasers. The chief corn trade of the town is now done by

auction at the fat stock market, which is held on Mondays. There was a

market-house at Tring in 1650, with a court loft over it, in which was

held the court baron and leet of the manor.”

Victoria County

History ― Hertfordshire (1908).

Direct cross-country routes would have been taken, which, over time and

through customary use became a ‘way’ (footpath, lane or road).

Other reasons for a way into a town developing were the need to

transport building materials (flint, bricks and tiles) by packhorse from

local pits and brickyards, of which there were a number in the Saint

Leonards/Cholesbury area. There was also a need to transport grain

for malting and brewing in an age when, due to unsafe water, much more

beer was drunk than today.

And so, over the centuries, a network of ‘ways’ developed into the town.

By the date of the first Tring Estate map (1719) and that of Dury

and Andrews (1766), the town’s principal roads were established ― these

we know today as Akeman Street, Frogmore Street, Miswell Lane, Mortimer

Hill and Grove Road/Cow Lane.

Tring Grove, then a hamlet ― Dury and

Andrews c.1766.

Key: Gove Road, purple; Marshcroft Lane, green; Cow Lane

Blue; unnamed lane (now a footpath), red.

It seems that a windmill (vide map, top, left of

centre) once stood in the vicinity of

today’s Lakeside, from which the area ― still called ‘New Mill’ ―

takes its name.

The maps above and below illustrate a few instances of the changing face

of Tring in the Grove Road area. The Dury and Andrews map above

(c. 1766) shows the hamlet of Tring Grove. At that time, much of

the land in that area belonged to John and Mary Sear, who inhabited

Grove House. According to a contemporary description, their estate

comprised a large manor house, large walled garden, pleasure

ground and shrubberies ― the site of which Dury and Andrews mark on

their map ― together with farm land. Mary Sear died in 1807, by

then a widow. Sometime afterwards the property was let, but did

not survive long. In 1811 the house was surveyed and found to be

in a very dilapidated condition, and it was recommended that it should

be demolished and the materials sold. When this happened is not

clear, but Bryant’s

map of 1822 shows what appears to be the walled garden without the

house, while on the Ordnance Survey map below (1822-34), all trace of

Grove House has disappeared.

Other noticeable differences between the two maps are that the

road across Little Dunsley Field, shown above in red, has disappeared ―

although a footpath still survives ― while the hamlet of Dunsley is

bypassed by new road construction (yellow on the map below) built

c.1822, which corresponds with today’s

alignment.

The Brook Street/Wingrave Road/Tringford Road area also experienced

change during the first half of the 19th century. This followed

construction of the windmill and canal wharf at Gamnel c.1810, the Silk

Mill in 1823, and the Gas Works in 1850, while later in the century a

boat-building business (later to become Bushell Brothers) also opened at

Gamnel. New housing was later built along these roads, together

with a school (Gamnel Road School) and public house (The

Queens Arms), to serve these working in the area, much of which

survives. |

|

The Old Robin Hood, Brook End.

The vent of the pub’s

maltings (see also below) is just visible behind the second chimney.

The date of this watercolour is unknown. It shows the brook from

Tring Park, after which Brook Street takes its name, running beside the

Robin Hood Inn. The brook does not appear in old photographs, but

whether it was diverted or culverted is not known. The building on

the right is Wigginton Manor. It was here that Wigginton’s legal

affairs were dealt with, but the building was not a manor house.

Apparently wrongdoers from the village were brought down to Tring to be

placed in the stocks, which are just visible at the bottom of the

picture. |

|

An undated photograph of

Brook End.

Inclosure.

Inclosure (modern spelling ‘Enclosure’) came at the end of the 18th

century. It was the process of physically changing the landscape

to benefit the development of modern farming practices as technology

improved. Initiatives to enclose came either from landowners

hoping to maximise rental from their estates, or from tenant farmers

anxious to improve their farms. Originally, land enclosures took

place through informal agreement, but during the 17th century the

practice developed of obtaining authorisation by Act of Parliament.

Under the Inclosure Acts, open fields and common land were enclosed with

fences, hedges, ditches or embankments, thereby creating legal property

rights over areas that had previously been considered common land.

Inclosure was carried out on a parish-by-parish basis, in the process

changing the layout and size of fields, and thus the routes of roads and

other rights of way. Prior to inclosure, villages were surrounded

by large, hedgeless ‘open fields’ that were farmed in strips.

The plan below, from 1793, is a part of the set of plans for the Grand

Junction Canal then being built. It relates to the Wendover Arm,

and is interesting for showing the strips of common field that then

existed at Little Tring before inclosure took place. |

|

Each plan is accompanied by a schedule that gives, for each strip, its

tenant, its area (in acres, roods and poles) and how much the

canal company paid for it (although at the

time this plan was drawn up the land had not yet been bought). For

instance, in the plan above, strips 25 & 27 belonged to Drummond Smith

Esq.; strip 26 to James Harding; strips 1, 2 & 3 to Mrs Mary Sear (of

the Grove); strip 4 to William Butcher; and so on.

Inclosure first took place in Tring in 1799 under an Act of Parliament

of 1797 (37 Geo. 3, C. 35) entitled “An Act for

dividing, allotting and inclosing the open and common fields, common

meadows and common pastures and waste land and ground within the parish

of Tring in the County of Hertford”. A survey was made,

and the enclosure was drawn up on plans. The Act granted the

enclosure commissioner the necessary powers to create new public rights

of way, and new roads were included of a specified width:

“. . . . the said Commissioners, or any Two of

them, shall, and they are hereby authorized and required, in the first

place, to set out and appoint such Public Roads and Ways in, over, and

upon the Lands and Grounds by this Act directed to be divided, allotted,

and inclosed, as they shall think necessary and proper; and that all

such Public Roads and Ways (except Bridle and Footways) shall be and

remain Forty Feet wide at least, and shall be fenced on both Sides

thereof by such Person and Persons, and in such Manner, and within such

Time, as the said Commissioners, or any Two of them, shall order or

direct . . . .”

Not only was the medieval field strip system abolished in favour of

enclosed fields, but new roads and footpaths designed to improve

communications were also established for what today would be called

‘minor roads’ and also for the more important ‘carriage roads’.

All these roads had to be fenced and at least 40 ft. wide, one clause

from the Act stating that:

“. . . . after the said Roads and Ways shall have been set out as

aforesaid, the said Commissioners . . . . shall . . . . appoint some

proper Person or Persons to be Surveyor of the said Carriage Roads; and

such Surveyor shall cause the same to be properly formed and put into

good and sufficient repair . . . . And that none of the Inhabitants of

the Parish of Tring shall be charged or chargeable …. towards the

forming or repairing of the said Roads until the same shall be made fit

for the passage of Travellers and Carriages, and shall be certified so

to be by the said Surveyor”.

In Tring, these new ‘Roads and Ways’ leading from the main highway

appear, more or less, to have followed the existing routes, but some of

the road names have since been changed while others are now incorrect.

For more details see Appendix I.

During the mid-Victorian period, Tring experienced a building boom, and

the part of the town ― now a Conservation Area known as the ‘Tring

Triangle’ ― became built up. The Local Board, comprising

elected members, decided on the line of new streets, and much land

changed hands. James Honour, a prominent local builder, was

requested to submit a street layout plan for the western side of Tring.

As with any committee, matters did not progress smoothly, and in 1865

one in a sequence of rows is reported, when “the

Clerk resigned on account of the publication of a printed circular

signed by the Chairman in which his ‘professional honour’ was called in

question. The Chairman again left the chair of the meeting, and the

question of Mr Honour’s roads was abandoned.”

Eventually, all was settled, the result being the network of small side

streets, some bearing royal names, on the south side of Tring. For

more details relating to the streets in the heart of the Tring Triangle

see

Appendix II.

Costs and Disputes.

Disputes over matters relating to roads were nothing new. Tring

Vestry Minutes record that prior to Victorian times, laws were passed in

the reigns of James I and Charles I applying to the supply and upkeep of

royal carriages for use on public highways. These demands were

considered outrageous by many ordinary citizens, including those in

Tring:

|

1625, January. At the Hertford Sessions, that whereas

for the earlier discharge of the King’s carriages the County in

general agreement in regard of the great disability of these

parts adjoining Theobalds and Royston, that the burden of such

carriages should be borne by contribution of the whole county,

but the inhabitants of the towns of Aldbury, Tring, Berkhamsted,

and the hamlets of Long Marston and Wilstone, and divers others,

obstinately refuse to pay the same and also refuse to appear at

the Sessions, or before any Justices. The Court now

desires certain Justices to attend the Board of Greencloth

[18]

to crave their assistance for the reformation of the said

abuses, by calling the said comtemptious [sic]

persons before them, and enforcing them to pay all such moneys

as are due from them.

1669, April 1st. At Hertford Sessions, presentations

by Sebastian Grace, John Dagnall, John Harding, Thomas Seabrooke

and John Foster the elder, all of Tring, that they refused to

assist in repairing the highway at Long Marston. |

Financial problems were sometimes settled amicably and sensibly, some

examples from the Tring Vestry Minutes include:

|

1767, 28th January. At a Publick Vestry it is agreed

between John Seare of Tring Grove, viz. that they will so as

they

[presumably members of the Vestry]

may, or can deliver at their own expense upon parts of the

commonly called New Road, 20 loads of stones annually towards

the repairing of the road and will excuse the duty John Seare

upon the other bye roads of Tring Parish so as he perform his

duty on the New Road without calling upon the Surveyors to allow

or provide anything further towards the repairs thereof. Signed

by John Seare and other names.

1822. During the engagement of Mr J H Maynard as

Surveyor of the roads in this county, he has rendered great

relief to different parishes; employing the superfluous poor

collecting and preparing materials, and introducing any

advantageous plan for improving the highways. In the parish of

Tring, Mr Maynard in the space of nine months, expended upwards

of £300 assisting the poor who otherwise must have been

supported by parish relief.

1826. At the Hertford Sessions, the inhabitants of

Tring were indicted for not repairing 2,500 yds. of road to

Chesham, starting at an oak tree in Little Meadow, the property

of William Kay Esq., at Hastoe Cross, and ending at a gate on

Cholesbury Common which marks the boundary between the counties

of Hertford and Buckingham. The Court discharged the case, upon

a certificate being produced that the road had been repaired.

1826. It was ascertained by Mr Rogers, one of the

Guardians of the Poor, that two of the men employed upon the

road in Akeman Street (Oakley and Nash) were neglecting their

work, and sitting by the roadside asleep. He therefore took up

their tools and discharged them. They both said they “did

not care about being turned off their work”.

1838. A letter was sent to the Hertford Sessions by

the Sparrows Hearne Turnpike Trust stating that in consequence

of the great reduction in the income of this road occasioned by

the L & B Railroad, the trustees find that they are under the

necessity of throwing upon the county the repair of all county

bridges on this road, and of 300 sq.ft. of the road at each end

of such bridges. They request that the County Surveyor be

instructed to attend to these repairs. |

Local costs were scrutinised in detail and with care, and sometimes

matters had to be thoroughly investigated. It is not recorded how

these examples below from Tring Vestry Minutes arose:

|

1856, 2nd May. Tring. J Grover’s accounts as Surveyor

of the Highways were brought before the Vestry who refused to

pass them. The Reverend James Williams of Tring Park said

that he strongly objected, and they must be examined by the

magistrates.

1856, 28th May. Tring. J Grover’s accounts were

brought before the magistrates, and after some discussion they

were ultimately passed. With the exception of £4 Grover

had incurred for Law expenses, which were not allowed, and

Grover must pay them himself. General satisfaction is felt

in the town at the result and gratitude to the Reverend Williams

for his stand in this matter. |

Drains and Lighting.

Ten years later, concerns were being expressed

about the dire state of Tring’s drains, and deputations from the Local

Board travelled to large towns such as Northampton to seek advice on the

matter; in 1866 a very large sum was borrowed and improvements gradually

started to be implemented, as well as the on-going work entailed in

providing a mains water supply.

In 1870, the Grand Junction Canal Company came into legal conflict with

the Tring Local Board of Health over contamination of Tringford

Reservoir and the spread of disease:

“Part of the

drainage of this town

[Tring]

is carried away by a sewer which empties itself into the

canal-reservoir to the north. Before this sewer was made the

reservoir received only spring-water, a matter of some

importance, as some neighbouring villages drew their water from

the stream that flows from the reservoir. After the

turning in of the sewer, in summer, when the water in the

reservoir was low, it stank abominably; and worse, diphtheria,

typhoid fever, and other such diseases, were frequent in the

villages.”

The Water Supply of Buckinghamshire and of

Hertfordshire, W. Whitaker (1921).

The canal company sued for damages. They complained of the

pollution and of the additional expense incurred in pumping water up

from Tringford reservoir that would otherwise have flowed directly into

the Wendover Arm along Tring Brook and were granted an injunction

against the Tring Board of Health, the Lord Chancellor ruling that “the

right of enjoyment of surface water in a flowing stream must not be

interfered with” ― public health issues did not appear to enter into

the argument! Standards of public health have of course improved

out of all measure since 1870, and today the canal summit obtains a

useful supply of cleaned water from Tring sewage works.

During the ten years preceding WWI the Council was again much

preoccupied by the essential question of laying a more modern sewerage

system in certain parts of the town. This work got underway in a

piecemeal fashion and major road works were again necessary as pipes had

to be laid beneath road surfaces.

Laying the new sewer in Langdon Street

aroused sufficient local interest for this

postcard to be made to record the

event.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX I.

Roads created from Tring by the Inclosure Act of

1799.

Wingrave Road was a continuation of Frogmore Street. It extended

from Bunstrux Hill through Little Tring and Tringford (i.e. the area

adjacent to Tringford and Startop’s End reservoirs) to Long Marston. The

present Wingrave Road in New Mill appears to be incorrectly named.

Winslow Road led from London Road at Pendley Beeches (i.e. the

wooded area to the east of the Cow lane/A4251 junction) passing along

Cow Lane and Grove Road to Wingrave Road at Tringford.

Windsor Way was the road forming the boundary between Tring and

Wigginton parishes set out under the Inclosure was half the specified

width at 20 ft. and this was paid for by Tring, the remaining half being

left for Wigginton to undertake. In the event, the villagers found the

20 ft. sufficiently convenient without further outlay.

Aldbury Road led out of the Winslow Road about halfway up Cow

Lane, it extended over what is now Pendley Park until it reached Aldbury

Parish boundary. This road was rendered redundant in 1838 following the

opening of Station Road.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX II.

Streets in the ‘Tring Triangle’.

Streets in the heart of the Tring Triangle:

[this information is obtained from various individuals – all now

deceased - and may contain errors!].

Langdon Street (known from 1711 as the ‘Gore Gap’) took its name

from George Langdon of Old Street, City Road, a linen manufacturer, who

died in 1827. He owned two pieces of land amounting to four acres

in Gravelly Furlong Road, an area on the east side of Langdon Street.

This straight road connected Park Road with the old road, which ran from

Abstacle Hill to Parsonage Bottom before Western Road was built in 1822.

A Primitive Methodist Chapel was built in 1842, replaced in 1870 by a

larger chapel now demolished. Langdon Street was taken over as a street

by the Local Board in 1866.

Charles Street was a short stretch of old road known as King

Charles Place. Extended in 1865, and set out to be 20 ft. wide,

the Local Board paid for the land at £3 a pole (1 pole = 5½ yards).

In 1866 the Local Board accepted an offer of land from John Brown, owner

of the Kings Arms, to extend Charles Street into King Street.

King Street was commenced at the east end by a Mr Edwin, who

built a block of four houses adjoining Langdon Street; later the

builder, James Honour, sold eight poles of land to widen King Street

from the Kings Arms to Chapel Street. In the late Victorian

period, the Reverend Arthur Pope, Vicar of Tring, erected The Furlong

for use as a clergy house and an Infants’ School, both now demolished.

Queen Street is of a more recent date and was once Gower Street.

For many years, a well-used sub-post office (now a private house) stood

on the corner with King Street.

Henry Street belonged to three Henrys ― two Henry Tompkins and

one Henry Adams. In 1862, after complaints by the vicar of Tring

that the street was in a dangerous state, notice was served on the

owners to put it in proper order before it was taken over by the Local

Board as a public highway.

The former Ebenezer Chapel after which

Chapel Street is named.

Chapel Street acquired its name after Western Road was formed,

and was formerly a continuation of another old road named Miswell (or

Windmill) Lane which ran from Icknield Way to the Park Road portion of

the coach road. It took its name from an Ebenezer Chapel which

seated 300 and was used by a congregation of General Baptists. Opposite

is a small Anglican church, St Martha & St Mary, - another of Reverend

Pope’s generous gifts to the town.

Albert Street named no doubt after the Prince Consort was formed

in 1864-66 on land owned by brewer, John Brown; some cottages were

pulled down to form the entrance from Akeman Street. In the

following year the Tring Gas Light & Coke Company laid a main. As

well as houses of different periods, the street contained several shops

and a boot factory, later to become the Salvation Army Citadel.

Akeman Street. It is not known why this road was so named, for it

does not form part of the route of the original Roman road. One of the

oldest streets in the town, until the middle of the 20th century it was

lined with shops and businesses, with small crowded courtyards

surrounded by houses leading off. Many of these were demolished after

the typhoid epidemic of 1899, when Lord Rothschild established a

rebuilding programme.

An undated view down Akeman Street.

――――♦――――

FOOTNOTES.

1. The name ‘Icknield’ is thought to derive from the Iceni tribe of

ancient Britons of Queen Boadicea fame.

2. Anglo-Saxon charters are documents from the early medieval period in

England, which typically made a grant of land or recorded a privilege.

3. Long before King Harold marched his army from York to that fateful

meeting with Duke William at Hastings in 1066, there were four major

highways covering the length and breadth of much of England, Watling

Street, Ermine Street, the Fosse Way, and the Icknield Way. From

the 10th century onward, these royal highways were maintained by order

of the king whose protection was extended to travellers making use of

them. However, there is some confusion about the identity of the

‘Icknield Way’ here referred to ― see footnote

9, Chapter 1.

4. The name of the present-day Akeman Street in Tring has nothing to do

with the route of the nearby Roman road after which it was named.

5. The findings of The Viatores were published in Roman Roads in

South East Midlands (Gollancz, 1964).

6. An ‘agger’ is an ancient Roman embankment or rampart, or any

artificial elevation.

7. Referred to in the Sparrows Herne Minute Book No.4.

8. ‘Bottle Cross’ ― a nickname derived from an ornamental cross of black

glass bottle ends set high in the gable of one of a row of (long

demolished) cottages facing Western Road.

9. Taking its name from ‘The Old Maidenhead’, an alehouse once located

on the corner of Park Road and Akeman Street. It was common in the

Middle Ages for plague victims and others with ghastly conditions to be

buried outside the city walls or in a designated area outside small

towns. It is thought that

“Pestle Ditch Way”

most likely referred to the place in Tring where such was the case.

10. ‘Gore Gap’, named after William Gore junior ― located on the corner

of High Street and Langdon Street.

11. From Hertford Quarter Sessisons Book, vol.7.

12. HRO, TP4/140. In the Bond, James Bull is shown as a ‘collar maker’

which refers to horses’ collars. In Trade Directories a little later he

is listed as ‘saddler and harness maker’ of Market Street, Tring.

13. Beggar Bush – a general name referring to the hawthorn shrub, and

meaning the place for those who had no alternative but to sleep under

the hedge.

14. HRO TP4 /140 ― Correspondence, tenders, contracts and bonds

relating to road improvement at Beggar Bush Hill, Buckland

(Buckinghamshire). Held at the Hertfordshire Archives and Local

Studies Office.

15. HRO TP4 /140 ― Correspondence, tenders, contracts and bonds

relating to road improvement at Beggar Bush Hill, Buckland

(Buckinghamshire). Held at the Hertfordshire Archives and Local

Studies Office.

16. HRO TP4 /140 ― Correspondence, tenders, contracts and bonds

relating to road improvement at Beggar Bush Hill, Buckland

(Buckinghamshire). Held at the Hertfordshire Archives and Local

Studies Office.

17. Until the Marriage Act of 1836, marriages had to be overseen by the

Church of England, even if the couples were not members. The 1836

Act allowed for non-religious civil marriages to be held in register

offices. These were set up in towns and cities across England and

Wales. The act also meant nonconformists and Catholic couples

could marry in their own places of worship according to their own rites.

18. A committee of the Royal Household taking its name from a

green-coloured table at which it was the custom for the Board to sit

when transacting business.

――――♦――――

[Next Page] |

|