|

|

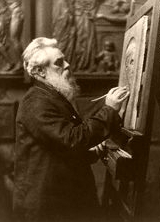

Thomas Woolner

(1825-92) |

THIS poem is

by a sculptor who has carried the realities of Pre-Raphaelite principles

into portrait sculpture with success. The poem is remarkable

for its gravity of feeling, its tender touches of beauty, and its

oneness. It shows us that the Poet of Form might have been a Poet

in Colour, and the life that has blanched in marble might have bloomed

in verse. The writer has felt for himself, thought for himself,

and made out his own music, with here and there a sign of invention in

measure and rhythm. He has an eye alive to external nature, and

the voice has the quiet emphasis of one who has been steadied by

suffering. The many loving thoughts and beautiful fancies

evidently blossom out of the real facts of life, and 'My Beautiful Lady'

is the work of a thorough artist. The writer has strong affinities

of nature and taste with those early Italian poets translated so

affectionately by Mr. Rossetti; and at times his quaintness of manner

may raise a smile, but we do not feel it to be an affectation, nor will

it be objected to by any reader who is one of the initiated in the

experience of loving and losing, and who knows that genuine grief will

have its freaks of fancy and quaintness of expression. The poem

was commenced years ago in the Pre-Raphaelite periodical called

The Germ. The seed there dropped has here expanded into an

acceptable flower, which, though springing from a grave, has fed on

sunshine and dew and taken healthy bloom from the open air.

The story, if story it can be called, is told, or

indicated, by the lover of the "Beautiful Lady," in various measures,

which change according to the changing theme. Here we meet with

the happy pair walking:

|

My Lady walks as I have watched a swan

Swim where a glory on the water shone:

There ends of willow branches

ride

Quivering on the flowing

tide,

By the deep river's side.

Fresh beauties, howsoe'er she moves, are stirred:

As the sunned bosom of a humming-bird

At each pant lifts some fiery

hue,

Fierce gold, bewildering

green or blue;

The same, yet ever new. |

That is in the sunshine. The

next is a Picture in the shade:

|

We wander forth unconsciously, because

The azure calmness of the evening draws:

When sober hues pervade the

ground,

And universal life is drowned

Into hushed depths of sound.

We thread a copse where frequent bramble spray

With loose obtrusiveness from side roots stray,

And force sweet pauses on our

walk;

I'll lift one with my foot,

and talk

About its leaves and stalk.

Or may be that some thorn or prickly stem

Will take a prisoner her long garment's hem;

To disentangle it I kneel,

Oft wounding more than I can

heal;

It makes her laugh, my zeal.

I recollect my Lady in the wood

Keeping her breath, while peering as she stood

There, balanced lightly on

tiptoe,

To mark a nest built snug

below,

Leaves shadowing her brow. |

In many lines the subject is

treated with such tender grace and quiet precision of delicate handling

that we know it is a shame to hint such a thing, and yet we cannot help

feeling that these walks in the woodland were continued too long and

late, and had something to do with the Lady's early decline and sad

death. The lover has scarcely sung his song of triumph,—

|

Warble, warble, warble, O thou joyful bird!

Warble, lost in leaves that shade my happy head;

Warble loud delights, laud thy warm-breasted mate,

And warbling shout the riot of thy heart,

Thine utmost rapture cannot equal mine.

Flutter, flutter, and flash; crimson-wingèd flower,

Parted from thy stem grown in land of dreams!

Hover and tremble, flitting till thou findest,

Butterfly, thy treasure! Yet thou never canst

Find treasure rich as my contented rest,— |

when he sees his "Beautiful Lady"

bowing with illness, and fading with the pallid droop of a lily, a

glance of "chilly splendour" in her eyes,—her

smile for him a "dawn-bright snowy peak,"—and

|

The heavy sinking at her heart

Sucked hollows in her cheek,

And made her eyelids weak,

Tho' oft they opened wide with sudden start. |

At length the end came, and he

stood

|

Awe-struck to see portentous loom

From her large eyes full gazing thro' the gloom,

Love darkly wedded to eternal doom. |

And now she lies mouldering down

into common dust:—

|

Birds twittering peck the variant weeds

That wave above this bed

Where my dear Love lies dead:

Their fluttering bursts the globèd seeds,

And beats the downy pride

Of dandelions, wide;

On spear-grass bowed with watery heads,

The wet uniting, drips

In sparkles off the tips:

In mallow bloom the wild bee drops and feeds.

No more she hears where vines adorn

Her window, on the boughs

Birds chirrup an arouse:

Flies, buzzing, strengthening with the morn,

She will not hear again

At random strike the pane:

No more on grass-plat newly shorn

With her gown's glancing hem

Bend down the daisy's stem,

In walking forth to view what flowers are born. |

In a blank verse

part called 'Years After,' the poem increases in strength of thought and

grasp of feeling. The poverty of the great loss has passed into

spiritual gain, and the "heartsease" has grown from out the grave of

buried love. The life-roots that felt the killing cold of the dark

earth have stirred with fresh sap, and the branches have put forth their

leaf of tenderer green at the coming of a later spring. Past

sufferings have purified the soul and cleared the vision for present

duties, and the love that shed such a light about the feet has now hung

up its little lamp of immortality overhead, safe beyond the region of

storms. The poem concludes worthily in a pæan to "Work":—

|

Men may seem playthings of ironic fate:

One stoutly shod paces a velvet sward;

And one is forced with naked feet to climb

Sharp slaty ways alive with scorpions,

While wolfish hunger strains to catch his throat;

One drinks his purple draught, smacks lip and laughs,

One shuddering tastes his bitter cup and groans;

But there is hope for all. Tho' not for all

To sail thro' sunny ripples to the end

Chatting of shipwrecks as pathetic tales;

All are not born to nurse the dainty pangs

That herald love's completion, and behold

Their darlings flourish in the tempered air

Of comfort till themselves become the springs

Of a yet milder race: all are not born

To touch majestic eminence and shine

Directing spirits in their nation's sight

And radiate unformed posterity:

But thro' transcendent mercy all are born

To enter on a nobler heritage

Than these, if each but wills to rightly choose

In serving Duty, man's prerogative:

Which is far pleasanter than paths of flowers,

Than warmest clustering of household joys,

And prouder than the proudest shouts of fame

That follow actions not in conscience wrought. |

Such a

conclusion to the poem, with its dawn of a nobler life and glow of purer

health, its removal of love's highest goal to the next life, its

unfolding of the new strength necessary to reach that goal, is natural

in the noblest sense, and for the work an artistic triumph. We

regret that the poem has not been better read by the printer; a thing we

have seldom to complain of now-a-days in books of verse. |