|

|

|

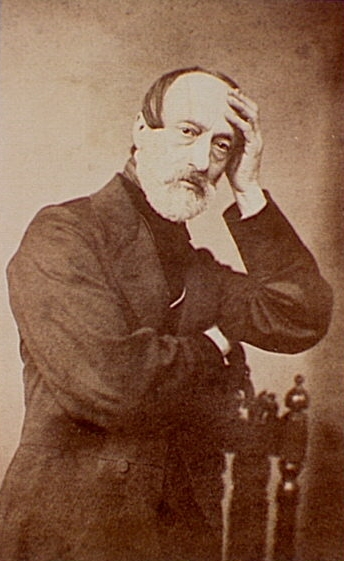

Joseph Mazzini.

(1805-72) |

Signor Mazzini has been, for years,

the best abused man in Europe. He has the misfortune to be

a republican; and, as if in illustration of Napoleon's remark,

that seems quite enough to turn a great many other people into

Cossacks, at the mere mention of his name. This, to some

extent, was shown in our own House of Commons lately, when a young, able

and eloquent servant of the state made a hundred sudden foes by

proclaiming himself Mazzini's friend. In the domain of

politics, it too often happens that names and nicknames,

words and watchwords, are accepted in place of

facts, and it is so much easier to do a great deal of wrong on the

surface of things than to penetrate to the real truth, and ascertain the

right which may underlie appearances. We should not dream of

going to our House of Commons, enlightened as it is, for the true

character of a man like Signor Mazzini. He will appear

better in history than in life. Such a man's chance is greater in

the literary than the political arena. We are somewhat

calmer; we can afford to be fairer. We remember that a great

Englishman, named John Milton, was a republican. We know that

another English, republican, Algernon Sidney, was a political exile.

These men had no justice from politicians in their own day.

They appealed to letters, and in literature their names became

immortal. It is before a literary tribunal that Signor

Mazzini now lays the facts of his public life.

According to his enemies this man answers to the

description of Coleridge's 'Ancient Mariner,' passing "like night from

land to land," and laying hands on any enthusiastic youth he may meet;

holding him with his glittering eye whilst he tells his strange story,

and, at parting, placing a poisoned dagger in the hand of the youth, and

pointing out the despot in whom the dagger is to find a sheath.

He is an ominous thing of darkness, like the Miltonic eclipse,

perplexing monarchs with fear of change—the red spectre of

revolution—the stormy petrel that heralds the tempest, and shrieks for

joy as the tide of destruction comes rising, rolling in. On

the other hand, his friends tell you that he has been as the dawn of a

better day for Italy. Around no modern name have opposing

hosts rushed to battle with a fiercer zeal. Many are the

martyrs who have gone to death proudly shouting this name coupled with

that of their beloved Italy. All who have known the man in

our country think nobly of him, and better of Italy for Signor Mazzini's

sake. In truth, we believe it was personal respect for him

which kept alive hope and effort for his country when times were dark

enough to make the English friends of Italy despair for the cause they

had at heart. Some of those who have known Signor Mazzini

best,—and these are not French policemen, but English gentlemen,—are

only too glad of an opportunity for testifying, with Mr. Carlyle,

that the calumniated exile is a man of genius and virtue, a man of

sterling veracity, humanity, and nobleness of mind.

In our opinion it is not too great a thing to say

that Signor Mazzini has done as much for the regeneration and

unification of Italy as his more famous compeer, General Garibaldi,

although it is not so easy to sum his work. All the world

can appreciate the man of action who does the great deed and sets it

shining in the dazzle of a great renown. His victory is

visible; we can see the work done. It is different with the

man of thought, whose greatest labour is accomplished in the dark; who

is compelled to work in secret, and keep himself as well as his doings

out of sight. The man of thought spends himself in giving

rootage to that new life which is destined to burst into full flower in

the victories of a man of action like Garibaldi. The many

can appreciate the glory of the flower, only the few think of the

rootage taken in the dark. Yet Signor Mazzini is to the

thinking few just what General Garibaldi is to the unthinking many.

Signor Mazzini was the first Italian of modern times

who saw that his country had a great future of new life before her.

He was one of the first to perceive that it was only sleep, not death,

which kept his country in her grave-clothes,—the first who had

sufficient faith to believe that she would wake and rise erect and

become a free nation. When most others despaired, or became

sceptical, he had faith that under the ruins of the past, the weedy

desolation of the present, there were springs of new life in the land.

He felt that, however effete the upper classes might be, however

helpless the

doctrinairés, there was still something sound in the heart of the

people; healthy blood enough to renew the whole body. He was

the first man in whom the idea of Italian unity became incarnate.

He saw and proclaimed the means of Italy's redemption, and devoted his

life to the attainment of that end. Through years of

suffering has he done desperate and determined battle for his idea,

given up friends and country and all the kindly comforts of home,

clasping to his heart a duty which to most men would be drear and cold

as a stone statue; fighting on from defeat to defeat, or sternly biding

his time in forced and desperate calm. For thirty years he

was the banner-bearer and lender of the forlorn hope for the unity of

Italy, before the flag waved out so triumphantly in the grasp of

Garibaldi. The successful fighter comes to remodel a country

and alter the map of Europe, but the exiled thinker marshalled the

forces and even sketched the plans of attack. It was

Mazzini's thought that leaped out in Garibaldi's deed; and it must have

been a proud moment for the thinker when the victor came to say how much

he owed to the lonely exile—making his way gently through the vast

crowds that embraced him so lovingly, and, with the world's eyes on him,

he went to pay his tribute to Mazzini, own how much he owed to his

teaching, and track the unity of Italy back to an almost forgotten

source.

It is now some forty-three years since Mazzini, then

a boy, was walking one day in the Strada Nuova of Genoa, with his mother

and an old friend of the family, when they were stopped by a tall

black-bearded man, with a stern countenance and a flaming eye, who held

out towards them a white handkerchief, merely saying, "For the

refugees." The Piedmontese insurrection had just been crushed, and

the wrecks of it, the revolutionists, came drifting to Genoa by sea.

Henceforth the boy was haunted by the thought of these men; and he used

to search them out and detect them by their appearance, their dress,

their warlike air, or by the signs of deep and silent sorrow on their

faces. He would have given anything to follow them; and they

awoke in him those dim yearnings which in after years caused him to

follow their footsteps, visibly printed in blood, along the path to

martyrdom. He began to study the history of their struggle,

and fathom the causes of its failure, until at length he fancied he had

found out

how the obstacles might have been conquered; for boyhood

supplies wings to surmount all obstacles. He thought and

thought, became sombre and absorbed, and appeared to have suddenly grown

old. Childishly enough, he determined to dress always in black,

fancying himself in mourning for his country.

Signor Mazzini's early tendencies and aspirations

were towards literature. Visions of historical dramas and

romances had floated before his mind's eye; poetic and artistic images

had wooed and caressed his spirit, but his long broodings over the

condition of his country led him to consecrate himself to sterner

patriotic work. He looked upon life as being more than

literature, and felt convinced that a free country and a noble national

life must precede any real vital Art, any worthy Literature.

He did not care to lend an artistic hand towards decorating a grave, by

flinging a few flowers to wither there; so he renounced all thought of a

literary career and struck into the rockier paths of political action.

This, he tells us, was his first great sacrifice. It was his

pen, however, that first drew attention to his name. He soon

became a member of the Carbonari, although no great admirer of their

complex symbolism and hierarchical mysteries.

So terrified, he says, were the governments of that

day at the revival of any memories calculated to make Italians think

less meanly of themselves, that they would have abolished history itself

if it had been in their power. He visited Guerrazzi, then

confined at Montepulciano for the offence of having recited a few solemn

pages in praise of a brave Italian soldier. The eye of

authority was soon fixed upon the young Mazzini, and he was speedily

within four prison walls, contriving to correspond with his friends

through the help of a little pencil which he had found betwixt his teeth

when eating the food sent to him front home. When his father

asked what the son was accused of, he was told that the time had not

arrived for answering that question, but that his son was a young man of

talent, very fond of solitary walks by night, and habitually silent as

to the subject of his meditations, and that the government was not fond

of young men of talent the subject of whose musings was unknown to it.

It was in his little prison-cell at Savona, up in a

tower, suspended betwixt sea and sky, that Mazzini got his first glimpse

of a great future for Italy. Looking through those

prison-bars, the first immature conception of Italian Unity and the

mission of his country inspired him with a mighty hope, that flashed

before his spirit like a star. It was then he saw the

possibility of a regenerate Italy becoming the missionary of a religion

of progress, unity and brotherhood, far grander and vaster than any that

she has given to humanity in the past. A new Italy with a

new Rome at its head, giving a new life to her people; a new word to our

world! The prison-walls faded away, but the dream stayed,

and the morning star of the patriot's life that rose so large and

beautiful still shines on as the evening star of the Exile's later day.

He says, "If ever—though I may not think it—I should live to see Italy

One, and to pass one year of solitude in some corner of my own land or

of this land where I now write, and which affection has rendered a

second country to me, I shall endeavour to develop and reduce the

consequences which flow from that idea, and which are of far greater

importance than most men believe."

Signor Mazzini found it was poor work trying to

strike a spark of life out of Carbonarism. His acquaintance

with Italian exiles in Francemade him feel sad and dispirited to find

how they were always looking for external help, always expecting the

great deliverance of one nation to come from another, instead of

believing that each must work out its own. The Carbonari,

he says, were mere sectarians, not the apostles of a national religion.

Intellectually, they were materialist and Machiavellian. The

ardour and energy of youth were intrusted to the direction of cold

precisionists, who had neither faith nor future. When the

time came for action on a national scale, they felt the want of a

sufficient bond of unity, and, not having a principle on which to found

it, they were always seeking for a prince. With leaders like

these, the Italian people, however ready to be led, never knew where

they were going! Signor Mazzini determined on starting his Society

of Young Italy. He believed that the salvation of his

country lay with the youth of it who would act, and not with a "class of

old-fashioned conspirators, who would diplomatize on the edge of the

grave." Nationality was to be the soul of his enterprise, and

Young Italy was to work for the nation's redemption, not be taught to

look for it elsewhere. It is true that Signor Mazzini placed the

Republic as a symbol beside the Unity of Italy on his banner.

He did not then, and, he tells us, does not now, believe that the

salvation of Italy can be accomplished by monarchy. "All that the

Piedmontese monarchy can give us, even if it can give so much, will be

an Italy shorn of provinces which ever were, are, and will be Italian,

though yielded up to foreign domination in payment of the services

rendered; an Italy the abject slave of French policy, dishonoured by her

alliance with despotism, weak, corrupted, and disinherited of all Moral

mission, and bearing within her the germs of provincial autonomy and

civil war."

Signor Mazzini had to begin his work, as he has had

to continue it, in exile. He had to erect on a foreign shore

his battery, wherewith he pounded the enemies of his own land who were

in possession. This was to fight at an immense

disadvantage. He was compelled to be an invisible leader of

men; a man of action almost shut up, far away from the scene, in a realm

of thought, and driven to work by subterranean means to the place where

he ought to have been openly in person; often doomed to marshal his

forces, plan the battle, and stand aloof to watch the failure, because

he was an exile.

In spite of all difficulties, however, Young Italy

was a success. Young men with souls virgin of interest or

greed, full of faith and chivalrous self-sacrifice, gathered round the

young chief, and they did a notable work. They sowed some

imperishable seed, and watered it lavishly with their blood.

They gave martyrs to their cause. And there is a time in the

history of enslaved nations when martyrs are not to be despised, however

these may be sneered at in later days. At least they enhance

the value of land, patriotically, by making some portions of the soil

sacred, and they leave an influence that works on in the minds of men

long after they are gone.

Signor Mazzini declares, "I never saw any nucleus of

young men so devoted, capable of such strong mutual affection, such pure

enthusiasm, and such readiness in daily, hourly toil, as were those who

then laboured with me." Their battery—the Press—was set up at

Marseilles, and Signor Mazzini's writings had to be smuggled into Italy,

sometimes inside barrels of pumice-stone, and even of pitch.

The little band baffled their ursuers and persecutors as they best

could, in many ingenious ways. Then, says Signor Mazzini,

"there began for me the life I have led for twenty out of thirty years—a

life of voluntary imprisonment within the four walls of a little room.

They failed to discover me. The means by which I eluded

search; the double spies who, for a trifling sum of money, performed the

same service for the prefect and for me—sending me copies of every order

issued by the authorities against me; the comic manner in which, when my

asylum was at last discovered, I succeeded in persuading the prefect to

send me away quietly, under the escort of his own agents, in order to

avoid all scandal and disturbance, and in substituting and sending to

Geneva in my place a friend who bore a personal resemblance to me,

whilst I walked quietly through the whole row of policeofficers dressed

in the uniform of a national guard;—it were useless to relate in these

pages, written, not for the satisfaction of the curiosity of the idle

reader, but simply to furnish such historical information or examples as

may be of service to my country."

In the year 1832, a certain Emiliani had been

attacked and wounded in the streets of Rodez, in the department of

L'Aveyron, by some Italian exiles. The men who wounded him

were sentenced to five years' imprisonment. In the year

following, on the 31st of May, this Emiliani and another person, both

being spies of the Duke of Modena, were mortally wounded by a young

exile of 1831, named Gavioli. At the time this deed was

done, Signor Mazzini avers that he had never heard of the existence of

these men; their aggressors were equally unknown to him. He

had nothing whatever to do with the affair. Nevertheless he

was charged with it, as leader of Young Italy, and the

Moniteur published the sentence of a secret tribunal with Signor

Mazzini's name as President and Secretary. This is

noticeable as the first calumny pinned with a dagger to his name.

At a later period, in 1845, Signor Mazzini reminds us, an English

Minister, Sir James Graham, who had revived the calumny, was compelled

by the information he received from the magistrates of L'Aveyron, to

ask Signor Mazzini's pardon in Parliament. But it was a lie

that took a good deal of killing, even if it be dead yet!

"Young Italy" was enthusiastically received by some

who have since been at enmity with it and its originators.

Gioberti chanted to it a sort of hymn of welcome.

There are working men, says Signor Mazzini, yet

living in Bologna, who well remember Farini loudly preaching massacre in

their meetings, and his habit of turning up his coat-sleeves to his

elbow, saying—"My lads! we must bathe our arms in blood."

Signor Mazzini writes a letter to Frederick Campanella concerning Signor

Gallenga, well known as a writer on Italy; not so well known as the

would-be assassin of the King, Charles Albert:—

"Towards the close of 1833, a short

time before the expedition of Savoy, a young man quite unknown to me

presented himself one evening at the

Hotel de la Navigation in Geneva. He was the bearer

of a letter from L. A. Melegari, enthusiastically

recommending him to me as a friend of his who was determined upon the

accomplishment of a great act, and wished to come to an understanding

with me. This young man was Antonio Gallenga. He had

just arrived from Corsica, and was a member of

Young Italy. He told me that from the moment when the

proscription began, he had decided to avenge the blood of his brothers,

and teach tyrants once for all that crime is followed by expiation; that

he felt himself called upon to destroy Charles Albert, the traitor of

1821, and the executioner of his brothers; and he had nourished this

idea in the solitudes of Corsica until it had obtained a gigantic power

over him, and become stronger than himself; and much more in the same

strain. I objected, as I have always done in similar

cases. I argued with him, putting before him everything

calculated to dissuade him. I said that I considered Charles

Albert deserving of death, but that his death would not save Italy.

I said that the man who assumed a mission of expiation, must know

himself pure from every thought of vengeance, or of any other motive

than the mission itself. He must know himself capable of

folding his arms and giving himself up as a victim after the execution

of the deed, and that anyhow the deed would cost him his life, and he

must be prepared to die stigmatized by mankind as an assassin.

And so on for a long while. He answered all I said, and his

eyes flashed as he spoke. He cared nothing for life; when he

had done the deed, he would not stir a step, but would shout

Viva l' Italia, and await his fate—tyrants were grown too bold,

because secure in the cowardice of others—it was time to break the

spell, and he felt himself called to do so. He had kept a

portrait of Charles Albert in his room, and gazed upon it until he was

more than ever dominated by the idea. He ended by persuading

me that he really was one of those beings whom, from the days of

Harmodius to our own, Providence has sent amongst us from time to time

to teach tyrants that their fate is in the hands of a single man.

And I asked him what he wanted with me—A passport and a little money.

I gave him a thousand francs, and told him that he could have a passport

in Ticino. Until then he did not even know that the mother

of Jacopo Ruffini was in Geneva and in the same hotel. Gallenga

remained there that night and part of the next day. He dined

with Madame Ruffini and me, but not a word passed between the two.

I allowed her to remain in ignorance of his intentions. She

was habitually silent from grief, and hardly ever spoke. During

the hours we passed together, I suspected that he was actuated by an

excessive desire of renown rather than by any sense of an expiatory

mission. He continually reminded me that since the days of

Lorenzino de Medici no such deed had been performed, and begged me to

write a few words explanatory of his motives after his death.

He departed and crossed the St. Gothard, whence he sent me a few

lines full of enthusiasm. He had prostrated himself on the

Alps, and renewed his oath to Italy to perform the deed. In

Ticino he received a passport bearing the name of Mariotti.

When he reached Turin he had an interview with a member of the

association, whose name he had had from me. His offer was

accepted, and measures were taken. The deed was to be done

in a long corridor at the court, through which the king passed every

Sunday on his way to the royal chapel. The privilege of

entering this corridor to see the king pass was granted to a few

persons, who were admitted by tickets. The committee

procured one of these tickets. Gallenga went with it unarmed

to study the locality. He saw the king, and felt more determined

than ever—at least he said so. It was decided that the blow

should be struck on the following Sunday. Then it was that,

fearful of obtaining a weapon in Turin, a member of the committee named

Sciandra, since dead, came to me at Geneva to ask me to give them a

weapon and tell them that the day was fixed. A little dagger

with a lapis lazuli handle, a gift, and very, dear to me, was lying on

my table. I pointed to it. Sciandra took it and

departed. Meanwhile, as I did not consider this act as any

part of the insurrectionary work upon which I was engaged, and in no way

counted upon it, I sent a certain Angelini one of our party, to Turin,

upon business connected with the association, under another name.

Angelini, knowing nothing of Gallenga or the affair, happened to take a

lodging in the same street where he lodged. Shortly

afterwards having through some imprudence, awakened the suspicions of

the police, he was returning one night to his lodging, when he perceived

that the house was surrounded by carabineers. He passed on,

and succeeded in escaping to a place of safety. But the

committee, knowing nothing about Angelini, and seeing the carabineers at

only two doors' distance from the house of the regicide, supposed that

the government had information of the scheme, and were Search of

Gallenga. They therefore caused him to leave the city, and

sent him to a country-house some distance from Turin, telling him that

the attempt could not be made on the next Sunday, but that if all things

remained quiet they would send for him on one of the Sundays following.

A few Sundays after they did send for him, but he was nowhere to be

found."

The first volume of Signor Mazzini's works ends with the memorable march

of the exiles into Savoy, under Ramorino, in the year 1834. |