|

|

|

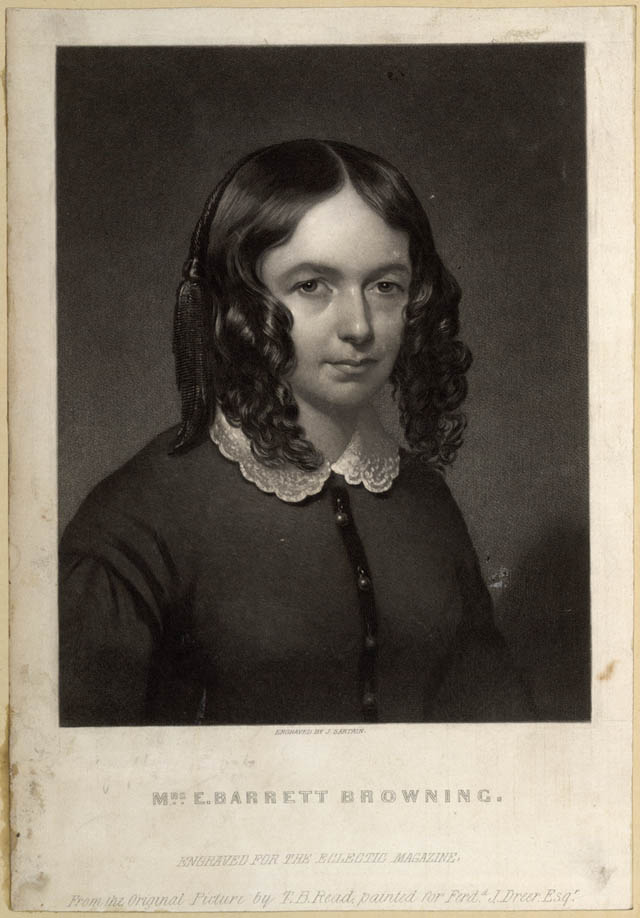

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

(1806-61) |

IN

his Essay upon Joan of Arc, De Quincey thus addresses Woman, not as the

general mother, but as the general sister: 'Woman, sister—there are some

things which you do not execute as well as your brother, Man; no, nor

ever will. Pardon me, if I doubt whether you will ever produce a

great poet from your choirs, or a Mozart, or a Phidias, or a Michael

Angelo, or a great philosopher, or a great scholar.' With perfect

fairness might our sister retort that there are many things which she

can execute better than her brother. She might also urge something

more to the point, in the fact that woman has done very great things

both in art and literature since De Quincey's words were written—the

greatest things probably she has ever done. She has not yet

produced her Shakspeare, her Newton, her Bacon, her Handel; and most

likely never will. But what she has done during the last twenty

years is quite sufficient to make man look down on her from his

intellectual throne with less of the smile of superiority. In more

than one department of literature she has run almost abreast of her

brother in the race. It is very doubtful if the highest and

richest nature of woman can ever be unfolded in its home life and wedded

relationships, and yet at the same time blossom and bear fruit in art or

literature with a similar fulness. What we mean is, that there is

so great a draft made upon woman by other creative works, as to make the

chance very small that the general energy shall culminate in the

greatest musician, for example. The nature of woman demands

that to perfect it in life which must half lame it for art.

A mother's heart, at its richest, is not likely to get adequate

expression in notes and bars, if it were only for the fact that she must

be absorbed by other music. That which makes the mother

wealthiest, will at the same time hinder the artist by at least

one-half. Thus a woman-Shakspeare would really have to be doubly

as great as the man Shakspeare, for he had not to bear a family with all

its precious burdens; nor does it appear that he paid very much

attention to his family when it had been borne for him. So that,

if woman should never stand on an equality with her brother at his

noblest height, she may fairly plead inequality at starting, and more

hindrances by the way. Great writers are the exception amongst

men, and they must be still more so amongst women. Women, who are

happy in all home-ties, and who amply fill the sphere of their love and

life, must, in the very nature of things, very seldom become writers.

For most women, the whole of life is uttered in the one word 'love,' the

whole world compressed in the one word 'home.' They live the

reality in such fulness, that there is no imperative need to seek refuge

in an ideal world. And then, where is the incentive to sing or

write? Perfect joy does not often set people writing. Joy is

a more unconscious thing than sorrow. The reason why sorrow

has inspired so many singers, is because it appeals so much more to the

consciousness. It turns the eyes more within. And then it

babbles, is more communicative, and loves to ease the heart of its

burdens by telling its troubles. It is also lessened by being

shared. Woman will seldom be able to 'catch up the whole of

life, and utter it;' it will generally be only the half of life, and

because it is only the half will she often strive to utter it.

Nevertheless, where the nature of woman is drawn or driven to seek

expression in art or literature, by all means let her have warm welcome

and brotherly cheer. She has many a tender and vivid revelation to

make which is sealed to man. But her deeper intuitions demand an

alliance with the most massive powers, ere the great books will be

written of which her nature affords the index.

In art and literature, woman has no past to speak of.

Never till our time has she come upon the stage so excellently equipped

for conquest, and with such a glory of intellectual power. Since

De Quincey wrote his words, we have seen Rosa Bonheur handling her

palette and pencil with manly mastery,—a worthy sister of Sir Edwin

Landseer himself. We have had fiery little Charlotte Bronté

emerging from those lonely Yorkshire wolds, with the wild Celtic blood

working weirdly in her English veins; the magnetic sparkle of uneasy

light kindling her eye, and holding the whole nation to listen to every

word of her strange, startling story. The ancient Mariner himself

was not more successful. We have seen George Eliot lay hold of

life with a large hand, look at it with a large eye, feel it with a

large heart. We have seen her lifting the film of familiarity, and

making the most commonplace lives most interesting. The low,

barren flats of life have been enriched by her humour and quickened by

her loving smile, until they have become more fertile than the most

highly cultivated plots of literature. And we have acknowledged

that, within novelist limits, she is almost a prose Shakspeare for her

knowledge of human nature, and her power in delineating character.

We might enumerate many more of our sister's latter triumphs, but have

to speak of perhaps her greatest. For De Quincey himself would

have admitted that in Mrs Browning we have woman's nearest approach to a

great poet. We call her the greatest woman-poet of whom we have

any record. Not a complete and perfect poet by any means; but

great in virtue of her noble fire of passion, her inspired rush of

energy, which vitalizes wherever it moves, and the good, true, loving

heart that beats through all her works,—thrilling tenderly or heaving

mightily. We often think it would astonish many writers of the

past who have been very much over-praised, and who got their fame just

in time, if they could see what is being done in our day, and has been

done since theirs. They would be surprised to find what a wealth

of delight there was in human life which they left untouched, what

depths of sorrow they never sounded, what heights of felicity they never

attained, or even saw clear of the mist; what new lands and waste places

have been brought into cultivation; what new worlds have been discovered

—Australias and Californias of literature, rich in virgin gold.

Not only would they be startled at the new mines opened, but also at the

manner of working them. The closer contact, the clearer

observation, and fuller detail, would seem quite as marvellous as the

ampler range. And so, if a poetess like Sappho could but see the

wealth of poetry poured forth profusely by Mrs Browning,—see what we

demand now-a-days before we apply the name of poet,—see the long years

of lonely toil, the slow accumulation of results, the variety and

combination of mental powers required,—we can fancy that she would

shrink from her own fame.

The publication of the 'Last Poems' of Elizabeth

Barrett Browning, as well as of the fifth edition of her collected

poems, affords us the opportunity, or rather seems to lay on us the

duty, of attempting a more full delineation of her genius than our pages

have yet supplied. Even should we be tempted to repeat passages

which are familiar to many readers, we shall readily be excused, on

account of the intrinsic beauty of the poems themselves, and the deeper

interest which they derive, both from the growing fame of Mrs Browning,

and the mournful fact that her 'Last Poems' have now been given to the

world.

As a poet, she stands among women unrivalled and

alone. In passionate tenderness, capaciousness of imagination, freshness

of feeling, vigour of thought, wealth of ideas, and loftiness or soul,

her poetry stands alone amongst all that has ever been written by women.

Her faults have too often furnished a subject for the critic and

criticastor during her lifetime for us to care to dwell upon them, now

we have heard the last thrillings of her harp-strings. They lie on

the surface of her works, and have their rootage in the depth of her

being, and circumstances of her early life. A certain

disproportion betwixt the matter and the manner at times is one of them.

But it would be very shortsighted to charge her with insincerity, when

she uses larger language than the matter may warrant; for the fault lies

in the strength of her sincerity striving and struggling with stammering

lips, and insufficient mastery of the force within her. Again,

there was some flaw in her musical faculty. She seems to have had

the lyrical impetus, the real leaping of the soul into song, without

the power of making the words dance to the internal tune. Her

strongest feelings could not fuse the music into sufficient fluency, her

most pressing thoughts did not 'voluntary move harmonious numbers.'

This makes many of her noblest lyrics difficult to read, and lessens the

enjoyment.

Her work is always best when she is most restrained

by the nature of the subject, or the stress of the measure. Her

great strength, full of starts and ebulliant overflows, moves the more

steadily and gracefully in proportion to the weight of responsibility or

fetter of form which she carries. In the 'Portuguese Sonnets,' for

example, the fiery spirit is subdued into a softer and more womanly

strength. The great heart heaves more gently, the passionate voice

is low with a murmuring tenderness. In 'Casa Guidi Windows,' the

measure does much to keep the straining mental vigour within bounds.

In 'Aurora Leigh,' we see, as it were, all the proud wilfulness and

audacity and quick blood of a magnificent girlhood, in which nature is

far too strong for the ties of custom or the formalities of art.

Stirred to the depths of her being, and inspired with a purpose, she

lashes out in all directions, and her energy exposes all her faults and

failings. The voice is often elevated beyond the

musical pitch. Her mind often flashes out its thoughts in the

zig-zag of the lightning, as it were, rather than in the straight line

of solar light. We are frequently more impressed with the display

of force than with the amount of work, and feel inclined to say with the

Scothwoman to Dr Brown when he put forth so much superfluous strength to

'catch a crab,' and fell backwards in the boat,—'Less pith, and more to

the purpose.' Again, in her prodigal abundance, she sows her seed

of thought too thick and too fast,—forgetting that the crop does not so

much depend on the quantity sown, as on the proportion that takes root,

and that too much brings forth too little: half would have been better

than the whole.

Another fault is that of incongruity. This

undoubtedly arose from her education, and from her spending her early

life so much apart. But many of her apparent incongruities,

arising from remote allusions, are increased, if not occasioned, by the

reader's not detecting the connection, from not knowing or not

remembering at the moment the fact that supplies it. One of her

critics, for instance, takes her to task for these lines:—

|

Never flinch,

But still, unscrupulously epic, catch

Upon the burning lava of a song,

The full-veined, heaving, double-breasted age:

But when the next shall come, the men of that

May touch the impress with reverent hand, and say,

Behold, behold, the paps we all have sucked! |

And he cries out against the savage

contrast of burning lava and a woman's breast, because in the latter are

concentrated the fullest and sweetest ideas of life. But that was

not the side of the metaphor which was uppermost in the writer's mind,

or which will flash first in the mind of any one who recalls the lava

mould of that beautiful bosom found, if we remember rightly, amongst the

ruins of Pompeii.

Another charge has been brought against Mrs Browning,

that her language is at times coarse, and her boldness almost

irreverent. The same thing has been urged against Charlotte

Bronté. In both cases the breadth of utterance is the result of

unsullied purity of thought and feeling. Women like these, of free

and lofty spirit, who have lived apart from society, are frequently

unconscious of that which appeals most to the consciousness of others.

But it should always be remembered, that it is the high privilege of

virtue to be able to speak what vice would blush to utter, and to know

no shame. It may be that, in such a matter, we are the furthest

from the noblest nature,—not the writers who maintain their prerogative

of plain speaking.

One great defect in Mrs Browning's mental character,

which is the parent of many defects in her poetry, is her want of

humour. This is one of the quickest and most clear-sighted of all

the faculties, and as keenly alive to the incongruous in ourselves as in

the acts of others. It has the power of enlarging the eye, making

the look calm, the head wise, the wisdom ripe. It is always

putting forth kindly feelers, and trying to embrace the whole world in

its geniality. It lubricates dry places, puts a smile into the

saddest aspect of things, makes allowance for discrepancies, and has a

sympathy with the crippled intentions, the arrested developments, the

premature failures of life. What the faculty of humour is worth to

a writer, may be seen in George Eliot's works, where it has flowered in

such quiet fulness as may not be seen more than once in a century.

This want in Mrs Browning may have been in great measure a matter of the

physical health. If the humour of abundant life with its overflow

of animal spirits, could but have run riot for awhile through her veins,

it would have effectually cleared her blood of its early sick-room

taint. This brings us naturally to the life which she lived, and

out of which she made her poetry.

The world in

general has got its first glimpse of Elizabeth Barrett through Miss

Mitford's kind old eyes, that dwelt so lovingly on the young

Greek-student girl, living her lonely London life with books for

companions, instead of women and men. We have seen an early poem

of hers on 'Mind,' or some such title, printed earlier than the

classical period of her studies. It showed the brain at work

before the heart had sent up its inspirations. It revealed a young

poet of such parts, that she needed all that we sum up in the word

'life,' to ripen her nature, and do justice to her great gifts.

Every shoot put forth by her expanding existence ought to have come into

contact with such kinds of food as would have assimilated healthily.

These should have been—grasping the human world, and the world of

flowers and leaves, beasts and birds. The sea, it seems, should

have sent its salt freshness, the old grey mountains have contributed

strength, the green country its sweetnesses, the spring-wind should have

given her blood a brighter bloom, the blue heaven and golden sunshine

have made her spirits dance within her; and these should have led her

out with ruddy cheek, happy light heart, and ready hand, into the

companionship of live human beings, all of which might have enriched her

nature by giving or receiving. Instead of this, we hear of the

early doom indoors, the dim life in the sick-room, the mental life

kindled and burning at the expense of the physical, the long train of

many sufferings, the way of life sad and shadowy to be walked wearily in

ill health, and the vista marked across at the end with an early grave.

Such was the life and prospect which have been sketched for the young

poetess in her early years. We doubt whether in this case, as in

others, the lot was really so bad as our imaginations are apt to colour

it, especially when it has been drawn by the imaginations of others.

We have met with people who have assured us that the sisters Bronté by

no means lived the dismal life that we had realized; and that, amidst

all the loneliness and misery, they often managed to extract a good deal

of pleasure from life. Still there was enough shutting up, in the

case of Elizabeth Barrett, to set her mind growing in the world of books

when it ought to have been expanding in a world warm with life: the mind

was growing, as it were, in a dark cellar, when it should have been

shooting and striking root out of doors under the breathing influence of

spring.

The whole tendency of this life was to grow apart

from that material which is the very clay in which the poet works.

At any time, the strong imagination has difficulty enough to get

fleshed, as we may phrase it, so as to dwell in common human forms, walk

in common human footsteps, and speak our common human language. It

is no easy matter to catch Pegasus, and put him into harness. But

when the outer world is mainly closed, and the inner world of

consciousness unhealthily quickened and stimulated, the difficulty of

bringing the imagination to bear for working purposes is many times

greater. Ordinary men and women grow up naturally in the ordinary

forms. They are moulded to the ordinary condition of things, while

the consciousness is awaking gradually. They seldom feel lost with

surprise at the state of matters in which they have grown up. They

do not feel eager to use the stride of a disembodied spirit, and so step

forth over this world's boundaries. They take kindly to the law of

gravitation. They are fitly fleshed, and don't hear the music of

the spheres, but are quite content to tread in the everyday track.

If strongly moved by emotion, the soul can find room to palpitate within

the senses, and is not for ever trying to flap its wings without, and

soar over the heights that hem it round. There are spirits,

however, that seem not to grow up in this natural way, receiving food

and growth through the senses. They appear to have dropt on the planet

ready made. They often go wailing round our world, and seek in

vain to get in: so they dwell apart, all eyes for the sorrows and

wrongs, the scars and rents of humanity; all ears for the cry of pain,

that is heard high above the music of pleasure,—low for very

happiness—because the voice of misery is shrill. They see all the

more of life's manifold mournfulness, because feeling so little of its

joy, that fills so many a life to the brim of felicity. They only

hear the ringing of the empty cup when it is dashed down? There

was something of this in Mrs Browning, and she found many doors into

life closed to her during those early years. This will account for

her endeavours to make a world of her own, not being native to ours,

which she did with an intrepidity of impulse more daring than man's

deliberate valour, or rather with the courage of a child that is not

tall enough to apprehend the obstacles which are visible to a loftier

vision.

From various causes, much of our modern subjective

mind is in a similar condition to that indicated by Sydney Smith, when

he described some small friend of his as having his intellect,

improperly exposed. It does not get sufficiently immersed in

matter for ordinary human contact. The matter is to be found in

human life. The poet must marry that. His love must be a

wedded love, and not a love apart, or it will fail of its rightful

issue. Milton was quite right in holding it necessary that the

poet should acquire an insight into all seemly and generous affairs.

Wordsworth, on the other hand, tells us of his feeling so much apart at

times, as to be compelled to clasp a tree in order that he might make

sure of his own identity. And we cannot help thinking that it

would do many others a world of good to clasp a wife or husband, and an

armful of children. Literature is, or should be, the expression of

life; and to reach a full and complete expression, the writer must live

the life in its manifold fulness and completeness. The poet must

take this world for better or for worse, and be united to humanity in

all its highest, and some of its sorrowfullest relationships. Mrs

Browning commenced far away from our ordinary world of women and men,

and her writing was, as a natural result, all too far from our business

and our bosoms. Our main interest in her, as she sits darkly in

the shadow of Æschylus, is one of curiosity and wonder. After

marvelling at the course of her studies, we marvel that she should not

have brought from them any touch of the Greek statuesqueness of style,

the marble calm of its form and finish. Evidently there was not

much affinity of nature to attract, or there would surely have been some

Greek likeness in the English poet's art. The reader must be

aerially equipped for travelling in cloudland if he is to follow the

poetess through several of her early poems. The atmosphere of

these heights is too rare for common human breathing, and the heights

themselves appear too unsubstantial and shadowy to offer any real

foothold, if they could be reached. Nevertheless, they show a spacious

mind, richly and diversely furnished; aspiration tending heavenward,

irresistible as burning flames, and a courage more glorified in failure

than much which has stood crowned with the world's success. She

has dared to grapple with such a subject as the Crucifixion, and look on

its agony through the eves of seraphs, who saw the sight, and heard the

cry that Heaven did not answer. Of this poem—'the Seraphim'—the

poetess speaks thus in her epilogue:—

|

I, too, may haply smile another day

At the far recollection of this lay,

When God may call me in your midst to dwell,

To hear your most sweet music's miracle,

And see your wondrous faces. May it be!

For His remembered sake, the Slain on rood,

Who 'rolled His earthly garment' red in blood

(Treading the wine-press), that the weak, like me,

Before His heavenly throne shall walk in white. |

The day for

smiling thus has now come for her.

Very many fine passages might be extracted from the 'Drama

of Exile,' and their brilliance would be always warm with heartheat,

their floweriness always fragrant. The most human thing—and it is

most piercing—is where the poor, fallen nature, having drunk of the

bitter cup, and added its clear seeing to the eyes, can forgive Lucifer

for very pity, and with such pathos of forgiveness, that he starts back,

stung by this unlooked-for revelation! For Adam is able to see in

the clear light of his great grief, that Lucifer has also fallen!

He comprehends by the vast brows, and melancholy eyes, and outlines of

faded angelhood, that he must have fallen from heights sublime; and it

must have been a mighty fall to his present place. What darkness

of desolation, what blank majesty there is in these lines:—

|

It seems as if he looked from grief to God,

And could not see Him. |

We must touch

upon one or two of Mrs Browning's smaller poems of another period, and

pass on to those of a later time. Here are a few

stanzas calmer and more musical than usual, and they linger in the

memory, soothing and unforgetable.

|

Of all the thoughts of God that are

Borne inward unto souls afar,

Along the Psalmist's music deep,

Now tell me if that any is,

For gift or grace, surpassing this,—

"He giveth His beloved sleep?"

What would we give to our beloved?

The hero's heart, to be unmoved,

The poet's star-tuned harp, to sweep,

The patriot's voice to teach and rouse,

The monarch's crown, to light the brows?

He giveth His beloved sleep.

What do we give to our beloved?

A little faith all undisproved,

A little dust to overweep,

And bitter memories to make

The whole earth blasted for our sake.

He giveth His beloved sleep.

"Sleep soft, beloved," we sometimes say,

But have no time to charm away

Sad dreams, that through the eyelids creep.

But never doleful dream again

Shall break the happy slumber, when

He giveth His beloved sleep.

For me, my heart that erst did go

Most like a tired child at a show,

That sees through tears the mummer's leap,

Would now its wearied vision close,

Would child-like on His love repose,

Who giveth His beloved sleep.

And, friends, dear friends, when it shall be

That this low breath is gone from me,

And round my bier ye come to weep,

Let One most loving of you all

Say, "Not a tear must o'er her fall:"

"He giveth His beloved sleep." |

The 'Romance of

the Swan's Nest' is naively natural in feeling, and exquisitely told.

Little Ellie sits alone musing to herself as she dips her naked feet in

the stream that flows musically by. She knows of a swan's nest

among the reeds, but will not tell the secret to any one until the

destined lover shall come; and after having done great deeds, and wooed

and waited long, he shall kneel at her knee, and to him she will

discover the swan's nest among the reeds. Having settled the

matter to her own smiling satisfaction, Little Ellie rises from her

dream, and thinks she will just peep in on the eggs, as is her daily

habit. Alas, the eggs are gone, the wild swan has deserted her

nest, and rats have gnawed the reeds. They who can see deep enough

may find a subtle allegory in the simplicity of this ballad.

'Bertha in the Lane' is a favourite with most of Mrs

Browning's readers, and it is one of her best minor poems. It is a

page from that red-leaved book of the human heart sacredly inscribed to

woman's hidden suffering. Nothing, perhaps, will more astonish us

in the next life than to see revealed the unknown self-sacrifice that

has been lived by woman in this life. Here is an instance which

the poet has made known. The elder of two sisters has been beloved

until the lover sees the younger one, when his passion pales for the

other, and kindles for her. The elder sees the change, and at

length hears of it unawares. She determines to give place to the

younger, and fold the robe of pain lightly about the breaking heart.

She is soon worn and wearied out in the struggle, innocently on her

death-bed confesses all to her sister, who has been so innocently happy

in her stolen love; but there must be no regret, as there is no

reproach.

|

I had died, dear, all the same;

Life's long joyous jostling game

Is too loud for my meek shame.

I am pale as crocus grows,

Close beside a rose tree's root;

Whosoe'er would reach the rose,

Treads the crocus underfoot. |

There is one last leap of the old

love, one flickering forth of the old affection before the life-flame

expires for ever.

He might come for a word of parting,—the poor heart listens!—

|

Are there footsteps at the door?

Look out quickly. Yea or nay?

Some one might be waiting for

Some last word that I might say.

Nay! so best, so angels would

Stand off clear from deathly road,

Not to cross the sight of God. |

The poetess is

coming nearer home to us, and getting closer to the beating heart of

humanity. Her hold of life is growing larger and surer, and

by-and-by she will win a gentle nestling place in the affections of all

true and noble lovers with certain sonnets called 'From the Portuguese,'

which were not found in the language of Camoens, but in her own womanly

heart.

These Portuguese sonnets contain a very tender

history. They are an illuminated leaf in the book of life that was

hitherto poor and pale, wanting the warm lights and colours of the

vitalest human affection. Hitherto the writer has lived apart

somewhere on the boundary of life, with the wan light of another world

whitening her face, and the dusky shadows of the past darkening it as

they hovered near. At times she seemed closer to them than to us,

and better fitted to understand them than hold converse with us.

She turned from the banquet prepared sumptuously with life's cates, and

wines, and dainties, and put aside the proffered pleasures. She

saw the happy faces, and felt the happy hearts in the ring of merry

voices, all the while fearful lest her own pulse should take too large a

leap. She looked and saw that it was good, but turned away

murmuring, 'Not for me; not for me.' The confession of this

self-abnegating soul being drawn gradually towards the marriage-feast of

noblest minds, all the while pleading its own unworthiness, and glowing

into highest beauty with the efforts of modest self-disparagement, is

one of the most 'secret, sweet, and precious' things in all poetry.

|

I thought once how Theocritus had sung

Of the sweet years, the dear and wished-for years,

Who each one in a gracious hand appears

To bear a gift for mortals, old or young:

And, as I mused it in his antique tongue,

I saw in gradual vision, through my tears,

The sweet, sad years, the melancholy years,

Those of my own life, who by turns had flung

A shadow across me. Straightway I was 'ware,

So weeping, how a mystic shape did move

Behind me, and drew me backward by the hair,

And a voice said in mastery as I strove,

"Guess now who holds thee?" "Death," I said. But

there

The silver answer rang, "Not Death, but Love." |

Although it is Love and not Death

that has caught her, the startled spirit urges her unfitness for Love,

her familiarity with Death. She still treats it as a mistake. She

pleads her unlikeness to the wooer. He is a guest for queens, a

singer of poems such as would make the dancers on palace-floors stop to

listen to his music, and watch his lips. Why should he pause at

her door, to let his music fall in golden fulness? The casement is

broken, the bats and owls build without the house; there is desolation

within. Such a shadow must not stand in his light. He must

go. Yet she will remember him in her prayers; and when she

beseeches God, He will hear the beloved name, and see within her eyes

the 'tears of two.' But soon there steals a new dawn over the face

of things. To love and be beloved makes a wonderful change in the

way of looking at life. Still, what can she, so poor, give back in

return for so rich a love? Nothing. No high gifts or graces.

She has nothing to give but love. Perhaps there is something

worthy of acceptation in mere love! For when she murmurs to

herself the simple words, 'I love thee,' she stands transfigured, and

feels glorified; and the flush rises up from breast to brow with a ruby

large enough for others to see that it is the very impression made by

Love's signet-ring. Then comes this surprise of thought:—

|

Beloved, my Beloved, when I think

That thou wast in the world a year ago,

What time I sat alone here in the snow,

And saw no footprint, heard the silence sink

No moment at thy voice . . . but, link by link,

Went counting all my chains, as if that so

They never could fall off at any blow

Struck by thy possible hand. . . . Why thus I drink

Of life's great cup of wonder! Wonderful,

Never to feel thee thrill the day or night

With personal act or speech,—nor ever cull

Some prescience of thee with the blossoms white

Thou sawest growing! Atheists are dull

Who cannot guess God's presence out of sight. |

We feel it

almost sacrilege to go on summarizing these sonnets, for they have the

fairy fineness of the gossamer, the delicacy of dew all a-tremble, in

their loving delineation of tender minutiæ, such as love delights to

pore over.

|

I marvelled, my Beloved, when I read

Thy thought so in the letter, I am thine—

But . . . so much to thee? Can I pour thy wine

While my hands tremble? Then my soul, instead

Of dreams of death, resumes life's lower range.

I yield the grave for thy sake, and exchange

My near sweet view of heaven for earth and thee. |

The growth of a

new interest in life and this world is beautifully told. We are

made to feel how the fresh tendrils that love puts forth twine about the

soul, and hold it to earth. It is drawn towards a closer

nestling-place irresistibly, as the heart of the mother-bird is drawn

down into the nest full of new life. And from thence it looks on

the vast cold expanse around, and shrinks from the unknown region into

which its aspirations once soared.

|

Let us stay

Rather on earth, Beloved, where the unfit

Contrarious moods of men recoil away

And isolate pure spirits, and permit

A place to stand and love in for a day,

With darkness and the death-hour rounding it. |

With what

subtle, sweet casuistry she gradually convinces herself, at the same

time informing us with much delightful simplicity that men are more than

the visions with which she once lived, and that the gifts of God put our

best dreams to shame! And then how naturally this leaning together

of two hearts, until two persons touch, begets a desire of being

together, and this, again, brings forth the longing for

keeping together. The happy companionship of two makes the

loneliness of one all the more lonely!

|

Ah, keep near and close,

Thou dove-like help! and, when my fears would rise,

With thy broad heart serenely interpose. |

The reader will

easily surmise that we are now pretty close to the church door, and will

feel too reverent to set foot in the sanctuary. But, after our

eyes are veiled to the vision of marriage life, the closing confession

is still heard; and this was the full meaning of the heart's emphatic 'I

will,' when the knees bent at the altar with the great weight of its

love.

|

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth, and breadth, and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day's

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs and with my childhood's faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints; I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life! and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death. |

We have treated

these sonnets personally, and cannot help it. The veil of disguise was

always thin, the features were visible and unmistakeable within, and the

loving eyes glowed through it. Mrs Browning is always a personal

poet.

Almost all the great poets of our century have been

so. We cannot here enter upon a consideration of the causes which

make the Elizabethan poets dramatic and impersonal, and the Victorian

poets subjective and personal. But Mrs Browning, is remarkably and

intensely personal. She does not sing her song, and present you

with it as something apart from herself, finished and sent forth to the

world with the artist's love and farewell. You cannot separate her

and her poetry. She is patent in every line. Her own nature

is felt, her own spirit shines, her own voice pleads through all her

poetry. Not only is this so, but you are obliged, as it were, to

be with her in the act of writing. She does not sing to you in the

distance; she writes in your presence. You see the face flashing

white with thought, the eye kindled large with feeling, the hand

trembling in its eagerness to scatter round the thick-coming throng of

emotions, ideas, and fancies. Indeed, you hear the very scratching

of the hurrying pen on the paper. The great poets of the objective

class do not do thus, and yet there is in it a marvellous charm.

The larger number of readers of poetry prefer this kind of

relationship, to the personal poet; they can get so much nearer home to

the poet nature in this way,—the personality in flesh and blood is so

much more powerful with them than the ideal creations of the dramatists.

So that this kind of poets, and poetry, and way of working, has its

compensations,—after all that has been said against its narrower limits

and lowlier place.

Mrs Browning, we repeat, is intensely personal.

Her appeals have in them the sharp cry of a woman's voice, at times

piercingly pathetic. She does not solicit our sympathies merely

with pen and paper; but the poetess comes herself, and pleads her cause

in person. She goes straight to the heart of the matter, and does not

stand upon ceremony; right on through many a conventionalism she goes,

not careful to walk in the world's ways, or use its favourite phrases.

In that cry of the children, which is only second to Hood's 'Song of the

Shirt' in its expostulation with society, there is a striking instance

of her piercing personal intensity, where she presents the naked, warm,

beating, and bleeding child-heart in the path that so many are treading,

and sorrowfully asks if they can trample it under foot.

All the forming forces about her early life

undoubtedly tended to sharpen her mind to this personal point, and it is

natural that she should penetrate further, and win her greatest success

in this personal way. Being so little dramatic, having so little

will, or wish, or leisure to go out of herself, and enter into the

individuality of others, she is all the more effective in description.

It is here that she finds neither let nor hindrance, and her genius

reaches to its full stature. We may see this if we go back to the

time of 'Duchess May,' and that description of her mounting on horseback

in front of her husband for the double death-ride, as though it were

some mount of transfiguration, and she shone all over, glorified with

the spirit of self-sacrifice, as with a proud smile she lighted the way

to their dark bridal.

Her power in delineating by means of description is

equally great, whether she sets before us an angel whose 'eyes were

dreadful, for you saw that they saw God,' or she paints the portrait of

'Dog Flush,' the darling of luxurious fortunes, nursed and petted in the

lap of plenty, his two eyes looking out on you, golden-clear, from

between the long lazy ears, and every silken hair burnished with soft

splendour.

She could make of her descriptive power almost a new

art; a something which quite reversed the old ideas of the word

'descriptive' when applied to poetry, she could crowd so much meaning

into so few words. Take a few of her poet-pictures in

illustration:—

|

Here Homer, with the broad suspense,

Of thundrous brows, and lips intense

Of garrulous god-innocence.

There, Shakspeare, on whose forehead climb

The crowns o' the world. O eyes sublime,

With tears and laughters for all time!

And Schiller with heroic front,

Worthy of Plutarch's kiss upon't,

Too large for wreath of modern wont.

And Chaucer with his infantine,

Familiar clasp of things divine.

That mark upon his lip is wine.

And Burns, with pungent passionings

In his deep eyes.

And Shelley, in his white-ideal,

All statue-blind. |

Or glance for a

moment at that wonderful poem, 'Aurora Leigh,' and see how this power

runs through it, redeemingly and enrichingly, almost making up for all

the want of dramatic aptitude. What immortal touches it lavishes,

and what things to think over it supplies! To mention only a few at

random. Who can ever forget that description of the nestled

babe in its little soft bed, warm and ruddy with life, the tiny

'holdfast hands' which had closed on the mother's finger as it went to

sleep, and 'kept the mould of it;' and the blue eyes slowly opening wide

on its mother. Or the descriptions of Lady Waldemar, the beautiful

woman-serpent brightening with some new glory of colour, and enfolding

some fresh grace of form with every deadly motion, which show us that

the devil never stole on mankind more caressingly, or was more cleverly

detected and portrayed. The sketch of Lord Howe, too long for us

to quote, is perfect. So is that hint of Sir Blaise:—

|

Good Sir' Blaise's brow is high,

And noticeably narrow; a strong wind

You fancy might unroof him suddenly,

And blow that great top attic off his head,

So piled with feudal relics. |

The description of Marian Earle

driven forth—

|

The swine's road, headlong o'er a precipice,

In such a curl of hell-foam caught and choked. |

and of poor blind Romney, as he

stands pale in the moonlight, stretching out his arms towards the

'solemn, thrilling, proud, pathetic voice' of Marian. Here the

passion goes right to the heart-roots and shakes the tears down by

storm, from those who are not lightly moved.

Before writing 'Aurora Leigh,' Mrs Browning had done

far more in poetry than any other woman living or dead. In that

poem, she set herself to do what no man in our time has attempted: that

is, to recover the lost ground which the poets have given up to the

novelists. Many of our living writers of romance would, if they

had lived in the Elizabethan era, have written dramas in verse, instead

of prose novels in three volumes. The novel, however, seems now to

lord it over the whole world of incident, and, up to the time of 'Aurora

Leigh' at least, appeared to be pushing the poet out of the world, or

rather, was shutting him up closer day by day in his own narrow

subjective world, until he was somewhat like the criminal, the walls of

whose prison closed in on him hour by hour.

In 'Aurora Leigh,' Mrs Browning has made a most

plucky effort to break from this prison-house of poetry, and enlarge the

boundaries of the poet's outer world. To our thinking, she has

completely succeeded in competing with the novelist. She has given

a narrative-interest to her work which carries the reader along eagerly

to the end; at the same time she has scattered such a profusion of

thought, and such a wealth of fancies, by the way, that you may go back

again and back again for ever, and not gather up all the good things.

If the writer could have put forth as much strength of art in repression

as there is fervour of nature in ebulliance, if her force had only been

rounded with Tennyson's finish,—' Aurora Leigh' would have been by far

the greatest poem yet written in our century. Greatest it is in

virtue of its immense riches of poetry, and in the power which it shows

of clothing with immortality the spirit of our time. But it was

not evolved and finished with that pondering patience whereby the master

artists have reached their perfectness. There was not time enough

for such an amount of matter to acquire the highest shape. We

admit that 'Aurora Leigh' often has the look of much of our nineteenth

century work, and seems lettered with 'our time,' rather than for all

times. It not only reflects the life and thought of our century in

manifold aspects, but the work also mirrors the feverish haste, the

conflict of opposite elements, and all the perplexities and difficulties

out of which we are to escape, it seems, if we will only hurry on fast

enough. We are speaking of the building from the outside. There is

rich and rare work within. There is length, and breadth, and height;

looks of grandeur to 'threaten the profane,' and dainty filagree to

charm the fastidious; while so numerous are the golden lights of

imagination, that it seems to be one great flame of beauty!

There is pretty sure to be something in a work like

'Aurora Leigh,' which will not be rightly judged by the time in which it

is written; we mean in the relationship of material supplied by that

time to artistic purposes. A similar difficulty to that which the

sculptor meets with in arraying his marble in the dress of to-day, will

have to be faced by the poet who shall try to do what Mrs Browning has

done. The purists will cry out on much as being totally unfit for

poetry; the lovers of high art will exclaim against the introduction of

that which they consider so low. This is a matter not to be

settled these hundred years, and then we fancy readers will often be

thankful for many things which the critics of our time condemned as

unworthy. Especially will this be so with much that they have

objected to in Tennyson's 'Maude,' and Mrs Browning's 'Aurora Leigh.'

The great failure, artistically speaking, of the

latter poem, is in the author's almost passionately frantic endeavour to

clutch at the utmost reality. Now, we ourselves are pre-Raphaelite

in our reach after reality; that is, we look upon reality as the better

name for the highest ideal, because it puts the seekers on a surer road,

and in a truer attitude. But we do not ask that the realists in

painting or poetry shall show themselves to us with the muscles all

starting, and the forehead sweating in the strain after it. We

must not have the endeavour painfully thrust on us, that should be

hidden in the art. The reality should be reached as a matter of

course. The minutiæ, the slow step by step, and touch by touch, of

a loving and patient spirit, should all be concealed. It is for

the critical mind to expound and insist, to take the skeleton in pieces

and put it together again for our edification; it is for the artist to

clothe the skeleton with flesh and blood, and make it live.

There is nothing conscious or prepense in the

realism of Shakspeare. He can work with infinite detail, and

reach reality where never man did; but he does not set about doing it as

though he said, ' Now, see what a realist I am going to be.' All

is natural, and like the working of natural forces without personal

effort. He is so perfectly en rapport with his work, that

his mastery over it seems as natural as play. Of course, this

power could only be thus perfect in one whose familiarity with all forms

of humanity was so great, that he could put on purple in its palaces of

stately passion, or creep on hands and knees to peer into its dim caves

of crime. Mrs Browning is so much in earnest, that she cannot hide

her efforts to grasp at reality. She comes to her work of 'Aurora

Leigh' with a great flush and tumult of new life in her, and a stronger

grasp of this world. She has not chosen a subject, as Tennyson

does, to mould into perfect shape through years and years of calm and

patient toil. A purpose has seized her soul, and she must follow

it. She is tremendously in earnest, and she will be utterly real

on low ground as well as high, on commonplace subjects as well as on

rare. And so she goes at her work with brimmed eyes, and hurrying

lips, and beating heart. On, on she goes, with great bursts of

feeling and gushes of thought, that follow one another with a

spontaneity that is always surprising, often startling, and sometimes

savage. Look not for the calm and finish of a Greek statue

from such an attitude of mind, and such a woman's work. It is not

a statue, for it is shaped out of human flesh and blood. You see

the heart heave within a form vital from top to toe: there is fire in

the eyes, breath between the lips, the red of life on the cheek; it is

warm with passion, and welling with poetry, in the double-breasted

bounteousness of a large nature and a liberal heart.

These 'Last Poems' of Mrs Browning bring us to ground

that we have not yet touched on here—her love for Italy, her record of

personal impressions received in that land, and her many cries for its

deliverance. We need not now go back to 'Casa Guidi Windows;' and

we have little to say of the 'Poems before Congress,' save that we think

she saw the deliverer with other eves than ours, as he came over the

Alps in the great dawn of deliverance, arrayed in splendours not his

own, and inspired with other motives than his admirers at the time saw.

One thing we have to acknowledge, here as elsewhere, is the courage with

which she never hesitates to lift up her voice for what she considers

the right. She is instant in season and out of season.

Politics do not improve her temper, artistically speaking. They

are not calculated to calm such a throbbing heart as hers. They

will not bring forth any such quaint music as that from the song of a

tree spirit in the' Drama of Exile,' who thus rocks the listening sense

as on one of her own swinging branches—

|

The Divine impulsion cleaves

In dim movements to the leaves,

Dropt and lifted, dropt and lifted,

In the sunlight greenly sifted,

In the sunlight and the moonlight,

Greenly sifted through the trees.

Ever wave the Eden trees,

In the nightlight and the noonlight,

With a ruffling of green branches,

Shaded off to resonances,

Never stirred by rain or breeze. |

They will not

call up in all its delicate loveliness and pure splendour any more such

graceful fancies as this:—

|

So, young muser, I sat listening

To my fancy's wildest word;

On a sudden through the glistening

Leaves around, a little stirred, |

Came a sound, a sense of music,

which was rather felt than heard.

|

Softly, finely, it unwound me,

From the world it shut me in,

Like a fountain falling round me,

Which, with silver waters thin,

Holds a little marble Naiad sitting smilingly within.

|

Instead, we have such fierce

flashes as this, with its lightning like vividness. Anything more full

of awful suggestion than the two last lines we do not know:—

|

Peace, you say?—yes, peace in truth:

But such a peace as the ear can achieve

'Twixt the rifle's click and the rush of the ball,

'Twixt the tiger's spring and the crunch of the tooth,

'Twixt the dying Atheist's negative

And God's face—waiting after all!' |

Or such a picture as this of poor

Peter, in his present Roman difficulty:—

|

Peter, Peter, he does not speak;

He is not as rash as in old Galilee:

Safer a ship, though it toss and leak,

Than a reeling foot on a rolling sea!

And he's got to be round in the girth, thinks he. |

There are better things in these

'Last Poems' than the political. The poem 'Mother and Poet' is glowing

with noble fire. Here is one fine natural touch from it. The

speaker is a poetess and a mother, who has two sons dead for Italy:—

|

What art can a woman be good at? Oh, vain!

What art is she good at, but hurting her breast

With the milk-teeth of babes, and a smile at the pain?

Oh, boys, how you hurt! you were strong as you

pressed.

And I

proud by that test. |

There is a very touching plea for

Ragged Schools, and the children that may be found in our streets:—

|

In the alleys, in the squares,

Begging, lying little rebels;

In the noisy thoroughfares,

Struggling on with piteous trebles.

Wicked children, with peaked chins

And old foreheads! there are many

With no pleasures except sins;

Gambling with a stolen penny.

Sickly children that whine low

To themselves and not their mothers,

From mere habit,—never so

Hoping help or care from others.

Healthy children, with those blue

English eyes, fresh from their

Maker, Fierce and ravenous, staring through

At the brown loaves of the baker. |

We could have

wished to quote at length the poem called Lord Walter's Wife.' In

its dramatic fulness and fitness, it is perfect; the changes are

exquisitely managed, and full of delightful surprise.

But in taking our farewell of Mrs Browning we rather

recur to some of her earlier utterances, which first told us that

whatever deficiency there might be in her power of grasping this world,

and embracing the whole round of human life, her anchor was made sure

and fast to another world, and she could ride at rest or stem the waves,

in full reliance that if her 'bark sank 'twas to another sea.' The

life she lived apart had its compensations for her, and she was laying

up for the life to come, in that time which we have spoken of, when we

might have wished her to have been dwelling more in our common world.

What she then wrote was not sent forth to stir so fiercely in the bosom

of the time, but 'calm with abdication.' She could drop from her lips

words both calm and wise. Possibly these things are more to

her now than even her later writings, and they touch us more nearly now

she is gone. Amongst other soothing or cheering and

heartening things, we call to mind from her true Christian philosophy

those utterances in which she tells us how we overstate the ills of

life. Do we weep? then let us thank God that we have no greater

grief than we can find tears for. In tears the grief will arise

and depart. Thank God for grace, ye who only weep. We are

all too apt to do as fretful, restive children do when forbidden

out-of-doors: we lean against the window-panes, and sigh until our

breath dims the clear glass, and the prospect is confused, and we are

doubly shut in,—prisoners to the natural boundaries, and prisoners to

the breathings of our own impatience. The imaginations that were

given us to bring heaven down, we use in making the worst of this world.

We walk upon the shadow of hills, and pant like climbers.

We sigh so loud, that we frighten the nightingale from singing. We

take the name of holy grief in vain; for holy it is, because sacred to

Him by whose grief came all our good. We are too ready with our

complaints. Not seeing the meaning that runs through all life's

noises, we often murmur, 'Where is the measured music, the certain

central tune?' while the angels may be leaning down from their golden

thrones to catch it and smile, and whisper, How sweet it is! We

are sent on earth to toil; to wrestle, not to reign; to be patient with

our own troubles, and ready to speak a word of cheer to others who

suffer.

|

The least flower with a brimming cup may stand,

And share its dewdrop with another near. |

It is this ground we choose for

parting, because, if we ever meet again, it will be here.

The poetess is gone. Her work is finished,

however unfinished the works may be. Undoubtedly they but faintly

shadowed forth the magnificent soul that dwelt awhile in the weak

womanly form, as we judge by the efforts she made to get expression for

what was labouring within her. Yet we are grateful for all that

has been left to us by this most glorious amongst poetesses, lofty

amongst women, and, we doubt not, most blessed among happy spirits.

And we rejoice in the belief that such a soul yet lives to unfold all

its forces in other ways, and reach nobler successes than were possible

for it here.

|

Nor blame we death, because he bare

The use of virtue out of earth,

Who know transplanted human worth

Will bloom to profit otherwhere.' |

And whether we sit summing up the

poet's work on earth or silence guard her fame, we know,

|

That somewhere out of human view,

Whate'er her hands are set to do,

Is wrought with triumph of acclaim. |

GERALD MASSEY. |