THE TWO WORLDS

April 2, 1909

PROFESSOR MAX MÜLLER AND EVOLUTION.

SIR,—Profound respect (based upon a careful study of

his great works on religion, language, etc.) for years past leads me to

a gentle protest against the writer, W. H. Simpson, whom I think

somewhat unjust to the Professor. If non-evolutionists are running

round a beaten track or endless circle, very well, let it be so.

The track or circle is infinite, so there is room for all, but without

the work of Professor Max Müller there would be no modern or ancient

Spiritualist science and philosophy, because that erudite scholar proved

the source, origin, derivation, and significance of words or

name-symbols, and traced them to their source back of nature.

Spiritualists should study his works, for we owe him gratitude and

thanks for pointing out to us the source of religious names, types, and

symbols, and also giving us philological light and reason where before

all was dark and superstitious confusion; in fact, Gerald Massey's

works are continuations or reflections of Professor Max Müller's studies

and researches into the origin and derivation of language.

|

|

|

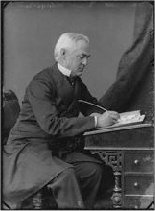

Friedrich Max Müller

1823 - 1900 |

Max Müller was "guilty of falsehood," says Mr. Simpson, "a

pseudo-scientific, semi-orthodox authority, unwise leader of the foolish."

All this because the Professor argued that "the ancestors of the human race had

a primitive intuition of God." Well, how is this disproved? Does

evolution deny it? Not at all, it confirms it, and so does W. H. Simpson,

for he goes on to say what the Professor does not deny, that "enormous periods

of time must have elapsed before our first ancestors were evolved."

Exactly! And when they were evolved, how does W. H. Simpson disprove that

he or they had a primitive intuition of God. Let us stick to the point,

and not fly off at a tangent, or abuse learned professors of language and

science, even if they do reside at Oxford. Let us not make a fetish of a

word. What is evolution? Why is the word opposed to the idea of a

primitive intuition by man of God? If evolution is still going on, where

does the theory for spirit continuance, identity, and permanence come in?

Mr. Simpson's argument causes him to do worse than run in a circle. He

runs away with himself and falls over himself. Vaulting ambition, as

Shakespeare says, lands him over the horse and flat on the other side. If

evolution for man means no beginning, no ending, but eternal progression, then

personal consciousness and persistency and identity of individuality beyond the

grave are a fiction and untrue. On the other hand, I believe the Professor

was right; that, go back ages, or cycles of millions of years for your first man

or men, and intuitively we must believe that primitive man had some germ

consciousness or spark of an idea of some Power or Being greater than himself.

If not, produce evidence to the contrary.

Eastwood-road, Rayleigh, Essex.

T. MAY.

____________________________

THE TWO WORLDS

May 7, 1909

PROFESSOR MAX MÜLLER AND EVOLUTION.

__________

W. H. SIMPSON

__________

I NOTICE in a back number of THE

TWO WORLDS a letter signed T.

May. This correspondent takes exception to some observations of

mine which occur in an article that appeared in a previous issue of this

journal. Not many years since, Max Müller spoke of " . . . a

primitive intuition of God, who had in the beginning revealed himself as

the same to the ancestors of the whole human race." These remarks

I characterised thus: "This announcement affords a good illustration of

falsehood confidently put forward to pass current as truth." This

is a perfectly fair criticism of the published opinions of any public

man, more especially as I endeavoured to justify my statement in the

succeeding part of my essay. And this was no more than saying a

theory provably false had been put forward as true. One might say

the same, without offence, of the Bishop of London proclaiming from his

pulpit an historical fall of Adam and Eve and an historical redemption

by Jesus. It would be quite another thing, though, to charge the

Bishop with intentional and wilful falsehood. Yet that is just

what I am accused of doing in the case of Professor Müller by my

assailant, who does not scruple to thus misrepresent what I say: "Max

Müller was guilty of falsehood, says Mr. Simpson."

There are people who cannot enter into a discussion without

at once becoming personal. I had no intention of descending to

personalities in this instance; it is not my mode of conducting a

discussion, strange as it may appear to one who seems to favour that

method himself, and who is so ready to put the most offensive

construction upon my words. As this gentleman has evidently failed

to understand the matters dealt with in my article, it would be quite

useless to enter into any further discussion with him.

We cannot take him seriously when he makes such an assertion

as the following: "Gerald Massey's works are continuations or

reflections of Professor Max Müller's studies and researches into the

origin and derivation of languages." This is very much the same as

saying Charles Darwin's works are but "contributions and reflections" of

the British and Foreign Bible Society. Mr. May must be jesting,

for it is quite impossible for any reasonable person to make such a

statement seriously. The whole of Gerald Massey's work for the

last forty years has been in direct opposition to all that was held to

be true by Max Müller. Massey has absolutely proved to

demonstration—by thousands of examples and illustrations—that all the

Aryan school of non-evolutionists, with Max Müller at the head, have

followed the wrong track, and are consequently completely and entirely

in error. There is no point of contact anywhere between Massey and

Max Müller. Massey starts at a different point, and arrives at a

different conclusion. The theories of the two men are as

diametrically opposed to one another as the Biblical creation and

evolution are.

In a criticism of the first great work published by Massey,

"A Book of the Beginnings," this is what Nature had to say about

the book: "It must he admitted that the author has a full right to

oppose that system of comparative philology which has been built up from

Sanskrit, the supposed oldest representative of the Aryan languages, to

the utter neglect of the older, Egyptian, Sumerian, Babylonian, and

Chinese. The stately edifice built upon the sand of Sanskritism

already shows signs of subsidence, and will ultimately vanish like the

baseless fabric of a vision." This prophecy is now fulfilling

itself. The edifice referred to here was upbuilt by Max Müller and

his followers—a structure that Gerald Massey's works have completely

demolished.

What did Sir Richard Burton, the marvellous linguist,

scholar, traveller, and explorer, say of Massey's work, writing in

The Athenæum:

"Gerald Massey has lately applied the key (Egyptian) to certain

hieroglyphics found in Pitcairn's Island, and it seems to me he has

struck the right line in his system (e.g., of the Kamite origins).

In the oldest times within the memory of man we know of only one

advanced culture, of only one mode of writing, and one literary

development, viz., those of Egypt . . . In working out the subject

his general view appears to be perfectly sound. He has met with

rough treatment from that part of the critical world which is lynx-eyed

to defects of detail, and stone-blind to the general scheme. He

has charged, lance at rest, the Sanskrit windmill, instead of allowing

the windy edifice to fall by its own weight. Still, his leading

thought is true: we must begin the history of civilisation with Egypt."

Thus it can be seen from these extracts that those who understood the

subject dealt with by Massey recognised at once that he altogether

disagreed with Max Müller, the chief exponent of man's Aryan origin, and

the Sanskrit school of philology. No one possessing the slightest

"knowledge of the nature and scope of Massey's investigations, and the

theory he deduces therefrom, could gravely assert that his works "are

continuations and reflections" of any previous investigators, "studies

and researches into the origin and derivation of language"; least of all

those of the very man with whom he was in direct conflict and to whom he

was opposed in every respect—Max Müller.

In the Dutch Litteraturzeitung, Herr Pitschmann,

speaking of "A Book of The Beginnings," remarks:

"This book belongs to the most advanced reconstruction

researches, by which it is intended to reduce all language, religion,

and thought to one definite historic origin. . . . The author, however,

differs from all similar writers in that he is an Evolutionist,

holding that he who is not, has not begun to think for lack of a

starting point. This view, of which modern philology has not

yet dreamed, has not hitherto had any Egyptian researches brought to

bear to its support. This the author saw, and saw also that

not only must one be an Egyptologist, but also an Evolutionist."

This passage clearly shows that Gerald Massey did not follow

in the footsteps of any predecessor, but that he struck out for himself

a new line of exploration. He even speaks with some contempt of

the Aryaniste and their Sanskrit philology. After reading the

first two volumes of Massey's work, Professor Alfred Russel Wallace

spoke of that book as a wonderful work, but expressed the fear lest

there might not be a score of people in England who were prepared by

their previous education to understand the book. Certainly my

critic is not amongst the number. But Mr. May, writing as he does

in so free and easy, so irresponsible and jocular a manner, cannot be

taken seriously. Perhaps he only intended to make a little cheap

and easy fun at my expense. If so, so be it. If he really

means in sober seriousness all he has written in his letter, then,

indeed, the engineer is hoist with his own petard. The joker has

outjoked himself, and we may all then join in the laugh that he has

raised against himself.

____________________________

THE TWO WORLDS

May 28, 1909

MASSEY, MÜLLER, AND EVOLUTION.

SIR,—A very few words are sufficient as reply to Mr.

W. H. Simpson's remarks on my previous note. First, I am not

joking, nor in the habit of even trying to joke on such subjects as

those in question. I stated that which Massey admits in his

"Natural Genesis" and last work on "Egyptology," that his researches and

Müller's were on parallel lines, or, as I put it, supplementary of each

other; they both aimed at a common goal, viz., truth. Massey in

several places states that he was indebted to Müller for indicating the

best path to take in sifting and sorting out the intricate, involved,

and apparently contradictory myths and legends of Egypt and India upon

religious origins. I have taken the trouble to study both

Massey and Müller, and Spiritualists, if they want to know the

truth, must go and do likewise. Perhaps an offer of mine may be

acceptable to Mr. Simpson, who repeats a platitude, which is over and

over again stated, regardless of truth, from Secularist and Spiritualist

platforms and papers, that "the Biblical creation and evolution are

opposed to each other." I shall be glad to give the sum of £200 to

Mr. Simpson, or any Spiritualist or Society he likes to name, if he can

produce any evidence from the Bible itself which is opposed to,

contradicts, or controverts the theory of evolution. The task is a

formidable one, considering that since the theory of evolution was

launched, say 20 years ago, there have been scores of books issued from

the press by reputable authors, showing that the Bible theory of

creation and evolution are not irreconcilable, antagonistic, or mutually

destructible. Mr. Simpson, I notice, quotes some anonymous

reviewer in an old number of Nature as an authority for Massey

versus Müller. I cannot congratulate him on his choice.

Still, we live and learn, and perhaps Mr. Simpson has some first-hand,

up-to-date evidence regarding Genesis and evolution. Why not ring

up Massey from Olympus and ask him to settle the point. When in

doubt, try the spirits, this is spiritual advice. But Dr. Johnson

tells us that it takes a hammer and nail to get a joke into a Scotsman's

head, so I had better say to Mr. Simpson, in the words of Mark Twain,

"This is not a goak."

T. MAY.

Eastwood-road, Rayleigh, Essex.

____________________________

THE TWO WORLDS

June 18, 1909

Professor Max Müller and Gerald Massey.

_________

W. H. SIMPSON.

_________

IN THE TWO

WORLDS of April 2nd a letter was published signed

"T. May." In the course of this communication the writer declared

that "Gerald Massey's works are continuations or reflections of

Professor Max Müller's studies and researches into the origin and

derivation of language." In my reply on May 7th I contradicted

this statement, which is erroneous, and supported my denial by

quotations from various reviews of "The Book of Beginnings," which

clearly indicated that those who understood the nature and scope of

Massey's investigations recognised that he was entirely opposed to the

system of comparative philology which Max Müller had upbuilt from

Sanskrit.

Mr. May has the assurance to assert in his latest

pronouncement, published in this journal on May 28th: "I stated that

which Massey admits in his 'Natural Genesis,' and last work on

Egyptology, that his researches and Müller's were on parallel lines, or,

as I put it, supplementary of each other . . . Massey in several places

states that he was indebted to Müller for indicating the best path to

take in sifting and sorting out the intricate, involved, and apparently

contradictory myths and legends of Egypt and India upon religious

origins." Yet Massey point blank denies Max Müller's fundamental

postulate of man's Asiatic origins, and proves by thousands of instances

that man's primordial home was Africa, and not Asia. Massey says

in the preface of "The Natural Genesis": "The main thesis of my work

includes the Kamite (African) origin of the pre-Aryan matter extant in

language and mythology found in the British Isles—the origin of Hebrew

and Christian theology in the mythology of Egypt—the unity of origin of

all mythology, as demonstrated by a world-wide comparison of the great

primary types, and the Kamite origin of that unity. . . the origin of

all mythology in Kamite typology—the origin of typology in gesture

signs—and the origin of language in African onomatopœa . . . Evolution

teaches us that nothing short of the primary natural sources can be of

final value, and that these have to be sought in the Totemic and

pre-paternal stage of Sicology, the pro-religious phase of mythology,

and the ante-alphabetical domain of signs in language." All this

was undreamt of in Max Müller's philosophy.

In the beginning of "The Natural Genesis" we read: "An

unfathomable fall awaits the non-evolutionist misinterpreters of

mythology in their descent from the view of a primeval and divine

revelation made to man in the beginning, to the actual facts of the

origins of religion. A 'primitive intuition of God,' and a God

who 'had in the beginning revealed Himself as the same as to the

ancestors of the whole human race' (Max Müller, 'Chips,' vol. I.,

pp. 366-368) can have no existence for the evolutionist. The 'primitive

revelation,' so called, had but little in it answering to the notion

of the supernatural. It was solely what early man could make out

in the domain of the simplest matters of fact." We are also

told by Massey: "... it has been affirmed by Max Müller, and maintained

by his followers, that the radical meaning and primitive power of

certain words (and sayings) must be obscured or lost for them to become

mythological; and that the essential character of a true myth

consists in its being no longer intelligible by a reference to the

spoken language (Comparative Mythology, 'Chips,' vol. IL, pp.

73-77). Such teaching of 'comparative mythology' is the result of

its being limited to the Aryan area, and if the myth be no longer

intelligible in the later

languages, we must look for it in the earlier" (see "The Natural

Genesis," section iii., p. 135).

Here it will be seen Massey absolutely denies and disproves

the conclusions previously arrived at by Max Müller. Again Massey

points out: "But words did not have their beginning in any known form of

the Aryan languages" (as asserted by Max Müller and others) "and

the proto-Aryan is unknown to them . . it is only by the aid of what is

here designated as Comparative Typology that we could ever reach the

stages of language in which the unity of origin can be recoverable.

Gesture signs and ideographic symbols alone preserve the early language

in visible figures. We are unable to get to the roots of all that

has been pictured, printed, or written, except by deciphering the signs

made primally by early man. The latest forms of these have to be

traced back to the first before we can know anything of the origins.

These are the true radicals of language, without which the philologist

has no final or adequate determinatives, and hitherto these have born,

left outside the range of discussion by Grimm, Bop, Pictet,

Müller, Fick, Schleicher, Whitney, and the rest of the Aryan school"

(see "The Natural Genesis," section v., pp. 241, 242).

At the commencement of this section, too, Massey remarks: "

The Aryanists have laboured to set the great pyramid of language on its

apex in Asia, instead of its base in Africa, where we have now to seek

for the veriest beginnings. My appeal is made to anthropologists,

ethnologists, and evolutionists, not to mere philologists limited to

the Aryan area, who, as non-evolutionists, have laid fast

hold of the wrong end of things." Massey also, in vol. I.,

p. 243, speaks of the Aryan school of philologists as ". . .the builders

up of language backwards." These passages speak for themselves,

and show that there is no justification for Mr. May's assertions that

"Gerald Massey's works are continuations or reflections of Professor Max

Müller's studies and researches into the origin and derivation of

language," or that "Massey. . .was indebted to Müller for indicating the

best path to take in sifting and sorting out the intricate, involved,

and apparently contradictory myths and legends of Egypt and India upon

religious origins." Max Müller, not being an Egyptologist, could

certainly have given Gerald Massey no information of any value regarding

Egypt. Massey, on the contrary, had studied Egyptology for ten or

twelve years, though he tells us he never puts forward his own readings

of the inscriptions unsupported by the best authority obtainable.

Massey, as an Evolutionist, commenced his inquiries into the

origin of language ages upon ages farther back than any previous

investigators. He started at a different, point, pursued a

different course, arrived at a different conclusion to Max Müller.

This is not merely a matter of opinion that may be held by one person

and contradicted by another. It is a matter of fact that cannot be

denied by anyone acquainted with the subject. "Mr. Simpson, I

notice, quotes some anonymous reviewer in an old number of Nature

as an authority for Massey versus Müller. I cannot

congratulate him on his choice," says my opponent. Since "The Book

of Beginnings" was published in 1881, necessarily the number of

Nature is an old

one; a book published more than twenty years ago would scarcely be

reviewed to-day. That, a criticism appeared in such a periodical

as

Nature is a sufficient guarantee of its value, even though it be

unsigned; besides, this criticism does not stand alone, as it was

supported by Sir Richard Burton and Herr Pitschmann, whose opinions of

the work I cited. "The Book of Beginnings," at the time of its

publication, was also favourably mentioned by The Modern Review

and

The Theosophist (Madras). This is what The Journal of

Science said of "The Natural Genesis:

"Mr. Massey is an independent thinker. After a

prolonged and laborious inquiry, he rejects certain modern theories as

to the origin of civilisation and the formation of language. He is

no believer in the Aryan hypothesis. . . He shows that

language is derived, not from abstract roots"—as Max Müller and the rest

of the Aryanists would have us believe—"but from signs and symbolic

actions far antecedent. . . For the first time perhaps we have

inquiries into primitive philology, mythology, and the early history

of our species untainted by the preconceived notion of an absolute and

quantitive distinction between man and the lower animals . . . The

section on 'Typology and Language' must ultimately give Comparative

Philology a new departure and a more rational character. . . We

would, indeed, bespeak for Mr. Massey's work the earnest attention of

all Evolutionists."

My antagonist seems anxious to start a fresh subject for debate, as shown

by this reckless proposition: "I shall be glad to give the sum of £200

to Mr. Simpson, or any Spiritualist or Society he likes to name, if he

can produce any evidence from the Bible itself which is opposed to,

contradicts, or controverts the theory of evolution." I am not

discussing evolution as applied to the Biblical account of creation with

Mr. May, and have not the least intention of doing so. Still, if

he is really so eager to come forward as the champion Biblical apologist

and reconciler of the irreconcilable, he has only to publish his

challenge in the Rationalistic press, say in Watts' Literary Guide,

and he will soon meet with an Evolutionist able to vanquish him and win

the £200.

Mr. May commences observations with this solemn assurance.

"First, I am not joking, nor in the habit of even trying to joke on such

subjects as those in question." And yet he winds up his letter

with these words:". . .it takes a hammer and nail to get a joke into a

Scotsman's head, so I had better say to Mr. Simpson, in the words of

Mark Twain, 'This is not a goak."' Mr. May disclaims all intention

of trying to be funny, and yet inveighs against the stupid Scotsman who

cannot see a joke which requires a nail to give it a point, a hammer to

drive it in. Doubtless there are people existing unable to

appreciate that peculiar form of jocularity indulged in by my

opponent—the hammer and nail style of humour.

______________________

[NOTE.—We

cannot devote further space to this discussion.—EDITOR.] |