Woodcut of a toll gate on the Islington turnpike road.

|

|

“In July, 1749, a great body of the country people of the county of Somerset came to Bedminster, shouting prodigiously, so as to be heard at a long distance off, and proceeded to attack the turnpike gates and toll houses along the Ashton Road, with axes, hatchets, and other implements of destruction, so as entirely to demolish them in about half-an-hour. Cross bars and posts were immediately erected in their room, chains were put across the road, and some stout men were placed to assist the toll men; but the next day these also were attacked, and summarily destroyed by a mob of people; their shouts alarming the city, to which it was feared they would proceed, and commence an attack upon Newgate and rescue the prisoners, which they had threatened to do. Public notice was given to the people to prepare for their coming, and defend themselves; the rendezvous to be at the Exchange, on the alarm being given by fire-bells. The rioters, however, did not carry out their threat; two of them, named Perryman and Roach, were tried at the next Taunton assizes, found guilty, and executed at Ilchester.” A Popular History of Bristol, George Pryce FSA (1861). |

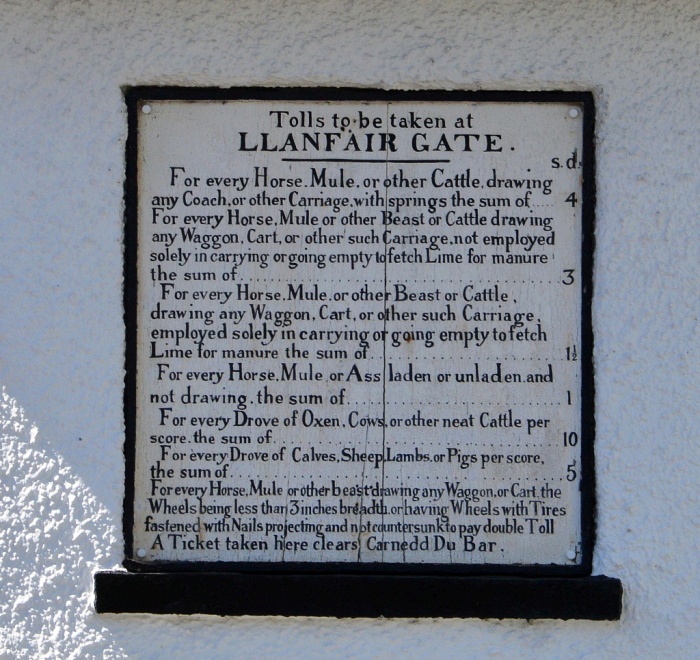

During the period 1839-43, there were further turnpike riots by tenant

farmers in west Wales protesting against the high level of turnpike

tolls. These were a big expense for small farmers, who used the

turnpikes to take their livestock and produce to market, and to collect

lime for use as a fertiliser (it could cost as much as five shillings in

tolls to move a cart of lime eight miles, at a time when an agricultural

labourer’s wage was about ten shillings a week). Named the

‘Rebecca Riots’, the rioters were men disguised as women, calling

themselves ‘Rebecca and her daughters’ after the biblical passage in

which Rebecca talks of the need to “possess the gate of those who

hate them” (Genesis XXIV, verse 60). They attacked the toll-gates

until the authorities quelled the riots using troops and the force of

the law. Some rioters were transported (Appendix).

A turnpike riot. Illustrated London News, 1843.

Social conditions gradually changed over the decade. Improvements

in the laws controlling turnpike trusts and the coming of railway

competition eased many of the transport problems in the areas.

People could move more easily to find work, while the ending of the Corn

Laws [7] and attempts to moderate the Poor Law also

helped.

The early part of the nineteenth century saw improvement in the

condition of the main turnpike roads as the work of Telford and McAdam

(see

Chapter 9) spread, and in the

progressive linking up of towns until most places of importance were

connected by stagecoach services. The improved roads then being

laid resulted in stagecoach speeds increasing from some 6 mph (including

stops) to 8 mph, [8] which greatly increased the level

of mobility for people and the mail. But despite the improvements

they had brought about, the end of the turnpike era was approaching.

The turnpikes were undoubtedly damaged by the coming of the canals in

the later 18th and early 19th century, but to a great extent the nature

of their businesses differed. Although some canals ran quick ‘fly

boat’ services for the conveyance of passengers and light goods, they

were uncommon. The canal carriers were mainly interested in

transporting bulk cargoes ― often long distance ― such coal,

stone/building materials and manure, to which road transport was not

well suited, as remains the case. But from the 1840s the new

public railways became a major factor in the financial failure of many

turnpike trusts and, for that matter, canals. Railways offered a

far quicker and cheaper service with which neither could compete. [9]

This applied particularly to long-distance routes; when a railway opened

along a route served by stagecoaches, the coach operator(s) quickly went

out of business, or had to convert to a railway feeder service.

By the early 1840s, many London-based mail coaches were being withdrawn,

the last being to close was the London to Norwich service in 1846.

Regional mail coaches continued into the 1850s, but they too were

eventually replaced by rail services. The poet Thomas Cooper at

first lamented the demise of the mail coach, but having experienced the

improved speed and comfort of rail travel, changed his tune:

|

I left the realm of silence by the

Rail. From Paradise of Martyrs, by Thomas Cooper. |

From the 1840s onwards, the steam-steeds’ arrival caused many

turnpike trusts to slip into insolvency, the outcome being that the cost

of road repair then fell on the very ratepayers who were paying the

tolls to use them. Thus, from 1864 onwards, Parliament embarked on

a programme of terminating turnpike trusts; any turnpike Act that had

not already expired, been repealed or discontinued, could continue to

operate no longer than 1st November 1886 unless Parliament declared

otherwise.

The last turnpike trust — that managing the Anglesey portion of the

Shrewsbury to Holyhead Road — expired on 1st November 1895. And so ended

the turnpike era. Under an Act of 1878 [10] a

new class of road emerged. All former turnpike roads that

had become public highways since 1870 were designated “main roads”,

as were roads between “great towns” and those leading to railway

stations.

Thomas Telford’s attractive two-story toll

house at Llanfair PG, Anglesey. The Anglesey section of the A5 was

the last public toll road in Britain until the M6 toll motorway opened

in 2003. There were five toll gates, each with a toll house, at

approximately five mile intervals between the Menai Suspension Bridge

and Holyhead.

The principal weaknesses of the turnpike trusts lay in their financial

structure. From the outset the heavy capital debt incurred in

their creation had to be serviced, and by 1830 there were cases of

unsuccessful trusts that had not paid interest on their bonds for 50

years. A further weakness lay in the absence of any central

control over the trustees, who were often slow to appoint efficient

officers. The treasurer would often keep toll receipts with his

own money; there was little effective control over the collectors, who

were often illiterate and unable to maintain accounts; and the process

of mortgaging tolls was sometimes so inefficient that there was little

income left for road maintenance. Ultimately, there was no

practical method of holding a defaulting, hopelessly incompetent or

dishonest turnpike trust to account. Subject to no official

supervision or central control, under no inspection, rendering no

accounts, a trust could use or neglect its powers as it chose; it could

not even be prosecuted for letting its roads become impassable!

Despite their failings, the turnpikes halted the deterioration in the

condition of main roads and slowly built up a network of reasonably well

maintained highways that allowed road transport to move more quickly and

reliably. In many cases the money raised by mortgaging toll income

allowed investment in road improvement, even in building by-passes

around bad sections of road. Although deadweight goods were still

carried more efficiently by water, until the advent of the public

railways road transport became the best means of carrying people, mail

and light goods rapidly between the booming towns of the Industrial

Revolution.

――――♦――――

The move towards a modern system of road maintenance developed through

the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the result of a

series of Acts of Parliament that progressively shifted this

responsibility onto larger and more structured bodies.

The turnpike era reached its zenith around 1838, but there were in use

many more miles of unturnpiked roads;

|

“. . . . we might easily have imagined that by this time the bulk of the roads throughout the kingdom had become turnpikes, and that the condition of such byways and country lanes as still remained under the jurisdiction of the parish Surveyor of Highways was of no importance. This was not the case. Out of a total length of recognised public highway in 1820 of about 125,000 miles, only about 20,875 miles, or little over one-sixth, was under Turnpike Trusts; and even by 1838 the mileage under Trusts had only increased to about 22,000, leaving, it was computed, no less than 104,770 miles, with an annual expenditure of more than a million sterling, under parochial control . . . . Even across rural parishes, especially in the eastern counties and in the south-west of England, many roads of more than local importance remained outside the network of the eleven hundred Turnpike Trusts.” English Local Government: the History of the King’s Highway, Webb (1913). |

The administration of these thousands of miles of unturnpiked roads

continued much as in Tudor times, when the responsibility was

transferred from the manor to the parish. The numerous parishes

and townships around the land appointed an unpaid, unskilled (and

possibly illiterate and/or corrupt) Surveyor of Highways each year, who

did what he felt necessary using the forced statute labour unwillingly

rendered on the roads (often by the parish paupers) on the six appointed

days each year. The law also required parishioners to provide

horses and carts, according to their means, to assist with the work.

The 1835 Highways Act consolidated and amended existing highway law not

affecting the turnpike trusts. Some advances were made; the Act

abolished statute labour — in operation for some 300 years and never

that effective — replacing it with a levy on the parish, the ‘highway

rate’. The duties of the annually elected surveyor of highways

became remunerated, and he could be fined by the county justices for

failing to keep the highways in repair. Improvements in road

engineering permitted the abolition of regulations that limited the

weights of loads to be carried, and the construction of wagon and cart

wheels.

But the Act’s weakness lay in confirming the parish as the

principal authority for repairing and maintaining unturnpiked roads.

In reality, a much larger geographical area, such as a county, was

needed to develop and deliver a strategic highways policy. The Act

did permit two or more parishes to apply to the justices to be united in

a ‘highway district’, having a salaried district surveyor, although each

parish remained responsible for its own assessment, rate collection and

expenditure. The supposed advantages that such amalgamation

offered were the employment of a more skilled person to supervise

repairs, greater uniformity of method, and greater efficiency in

management; but the provision attracted little interest.

The move towards larger highway units began in 1862. Under the

Highways Act of that year, [11] the Justices of the

Peace for a county were authorised, by means of a provisional order

confirmed by the Quarter Sessions, to divide it compulsorily into a

number of ‘Highway Districts’, each consisting of a number of parishes.

The order listed the parishes to be grouped together, the name to be

given to the district, and the number of ‘way wardens’ to be elected by

each.

The authority governing each Highway District was its ‘Highway Board’,

which comprised one or more members elected annually by each parish —

way-wardens — and any county justices residing in the district. It

was to appoint a treasurer, clerk and district surveyor, [12]

whose salaries and other administrative expenses were chargeable to a

district fund to which each parish contributed in proportion to the

3-year average spent on maintaining its highways. Other changes

regulating accountability and audit followed in 1864.

The long-lived role of the parish in highway maintenance was now reduced

to that of electing a way-warden(s) and levying whatever highway rate

was sufficient to meet the precept of the Highway Board — at least that

was the theory. There was no compulsion for Highway Districts to

be formed and, by using a loophole in existing local government

legislation, [13] a parish could become an ‘Urban

Sanitary Authority’, thereby retaining control of its highways together

with various public health matters, such as providing clean drinking

water, sewers, street cleaning, and clearing slum housing. In this

way many parishes continued to maintain their own highways for some

years to come.

In 1878, the Highways and Locomotives (Amendment) Act created a

single highway rate, thus preventing parishes being financially

independent, but it was not until 1894 that parishes were eliminated as

highway authorities altogether, thus ending a practice going back to the

reign of Henry VIII. [14] At the same time Urban

Sanitary Authorities were renamed Urban District Councils. In the

meantime, the 1888 Local Government Act transferred responsibility for

major bridges and main roads to the newly created County Councils. [15]

English highways were now administered, within boroughs or urban

district councils, by the town or district council; outside the urban

areas, main roads were the responsibility of the county council and the

others of the rural district council. The system of paid surveyors

and hired labour was now general, the cost being met out of local rates.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX.

TURNPIKE RIOTS

Reported in the CAMBRIAN, 16th Sept 1843.

THE PONTARDULAIS GATE.

(Extract from the report of Capt. Napier, Chief Constable.)

Just before we entered the village, I heard a noise, as if of a body of

men on the other side of the river. I also heard horns blowing,

and a great many guns fired off. I also heard a voice, like that

of a woman, crying out— “Come, come, come;” and a voice like the mewing

of cats. This noise appeared to me to proceed from the direction

of the Red Lion Inn, which is at a short distance from the

turnpike-gate. Immediately after this, I heard a voice crying out aloud

— “Gate!” and in a very short time afterwards I heard a noise, as if the

gate was being destroyed. I then proceeded with my officers and

men towards the gate, and on coming in full view, I observed a number of

men mounted on horseback, and disguised. Some had white dresses on

them, and others had bonnets. Most of them appeared to be dressed

like women, with their faces blackened. A portion of the men were

dismounted, and in the act of breaking the gate and the toll-house.

About three of them, who appeared to lead, were mounted, having their

horses’ heads facing the gate, and their backs towards me. At this

time there was a continual firing of guns kept up by the parties

assembled. I immediately called on my men to fall in, and proceed

towards the men who were on horseback, and who appeared to be taking the

lead, and called upon them, as loud as I could, to “Stop.” I used

the word “Stop,” three or four times. Upon coming up to them, one

of the mounted men, who was disguised as a woman, turned round, and

fired a pistol at me. I was close to him at the time. I

moved on a few paces, and a volley was fired by the parties assembled in

the direction of the police. I should say the volley was fired at

us — that was the impression on my mind at the time. I then

endeavoured to take the parties, the three mounted men in particular,

into custody. Myself and men met with considerable resistance from

them and the other parties. The three men on horseback rode at us,

as if they intended to ride us down and get us out of the way.

The three prisoners, John Hughes, David Jones, and John Hugh, were among

the parties assembled on the occasion, and were taken into custody.

――――♦――――

DESTRUCTION BY FIRE OF HENDY TOLLHOUSE,

AND DEATH OF THE TOLL COLLECTOR.

A report reached this town on Sunday evening, that the above gate, as

well as the Toll-house, had been destroyed, and that the toll collector,

an old woman, had been shot dead.

On enquiry it turned out that the sad news was but too true. It

appeared that the gate-house was attacked by a party of the Rebaccaites

at about eleven or twelve o’clock on Saturday night. The number of

persons assembled could not have been great, as, according to the

evidence of one of the witnesses at the coroner’s inquisition, neither

the noise of horses nor the trampling of feet was heard, but two

witnesses say that they heard the reports of five or six gunshots.

However, certain it is, that soon after the house was fired, the

collector, who appeared to be in her usual state of health, went to the

house of a neighbour, to seek assistance, after which she returned to

the toll-house, and as soon as she went for the second time to the home

of her neighbour, the unoffending old woman sank and breathed her last.

Further details will be learnt from the inquest held on Tuesday, on the

body of Sarah Williams, toll collector, aged 75 years, before William

Bonville, Esq., coroner.

――――♦――――

FOOTNOTES

1. An Act for the better repairing the Highway between Forn Hill in

the County of Bedford, and the Town of Stony-Stratford in the County of

Buckingham, 1706 (6 Anne c. 4).

2. Preservation of Roads Act, 1740 (14 Geo. II, c. 42). The long

title of this Act may have been An Act for Better Preservation

of Turnpike Roads, by limiting the Weight of Carriages, and erecting

Weighing Engines for that Purpose.

3. It was not until 1773 that a formal procedure was laid down by Act of

Parliament for auctioning the tolls (Turnpike Roads Act 13 Geo.

III c.84 art. 31).

4. The cost of obtaining new legal powers — generally every 21-years —

placed a significant drain on a turnpike trust’s finances. The 1823

Sparrow’s Herne Act cost £409 to obtain, a not insignificant sum at a

time when a farm labourer’s wage was in the region of ten shillings a

week.

5. Appendix B, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840,

William Albert (1972).

6. See “Turnpike

Roads” and “Turnpikes

and tolls” at www.parliament.uk.

7. The Corn Laws were measures in force in the United Kingdom between

1815 and 1846 that imposed restrictions and tariffs on otherwise cheap

imported grain. They were designed to keep grain prices high to

favour domestic producers. Their effect was to enhanced the profits and

political power of the land owners at the expense of the poor, who were

faced with artificially high food prices, the price of grain (hence the

term ‘Corn Laws’) being central to the price of their most important

staple food, bread.

8. On the subject of road speeds during the 19th century, mention must

be made of an Act known to history as the ‘Red Flag Act’ (The

Locomotive Act 1865, 28 & 29 Vict., c. 83). By the 1860s there

was concern that the widespread use of steam road locomotives would

endanger public safety. It was also alleged — probably by those

with business interests in railways and horse-drawn carriages — that

road locomotives damaged the highway when being driven at the current

speed limit of 10 mph. Despite there being no evidence to support

this claim, the most draconic speed restrictions resulted. Under

the Act, all road locomotives (which later included automobiles) were

restricted to a maximum of 4 mph in the country and 2 mph in the towns,

and a man carrying a red flag was required to walk in front of any

hauling two or more wagons.

9. “The tolls from eight trusts along the

London-Birmingham road, for instance, fell from £29,000 to £15,800

immediately on the opening of the London & Birmingham Railway

[September, 1838]. By 1848 the total receipts from all English

turnpikes had fallen by a quarter.”

pp 120-121, An Economic History of Transport in Britain, Barker & Savage, 3rd edition, 1974.

“Each stage-coach journeying daily from London to Manchester was

contributing over £1700 a year in turnpike tolls to the different Trusts

along the route. It was computed that each coach paid something

like £7 a year in tolls for each mile of road that it traversed.

The transfer of this business was instantaneous and complete.

Every coach had to be taken off the road the moment the railway was open

to the towns along its route. No one took a post chaise when he

could take the train.”

p215, English Local Government: the History of the King’s Highway, Sidney and Beatrice Webb (1913).

10. The Highways and Locomotives (Amendment) Act 1878 (41 & 42

Vict., c. 77).

11. The Highways Act 1862 (25 & 26 Vict., c. 61).

12. As late as 1881, it was claimed in evidence that the Surveyors of

Highways, were:

“. . . . farmers, millers, clergymen, squires when they were not gardeners, bricklayers, broken-down clerks or shopkeepers, or merely the incompetent relations of prominent parishioners. ‘I do not suppose ten per cent are competent,’ said the witness, ‘although many are paid.’”

Quoted p210, English Local Government: the History of the King’s Highway, Sidney and Beatrice Webb (1913).

13. The Local Government Act, 1858 (21 & 22 Vict. c. 98).

14. The Local Government Act 1894 (56 & 57 Vict. c. 73). It

was estimated at the time that some 5,000 highway parishes continued to

elect their surveyor of highways each year, and mend their own roads.

15. County Councils were created by The Local Government Act 1888

(51 & 52 Vict. c. 41) to be responsible for more strategic services in a

region with, from 1894 — The Local Government Act 1894 (56 & 57

Vict. c. 73) — the smaller urban district and rural district councils

being responsible for other activities.

――――♦――――

[Next Page]

|

|