|

“WENDOVER, a

market town and borough of England, in the county of

Buckingham. It is but an inconsiderable place,

consisting chiefly of mean brick houses, and possesses

no trade or manufacture of any consequence, except lace

making, from which the inhabitants derive their chief

support. A branch of the Grand Junction Canal, called

the Navigable Feeder, has been brought into the town,

which may be of some importance to its trade.”

The Edinburgh Gazetteer, or, Geographical

Dictionary

(1822)

Navigating the Wendover Arm at Little Tring.

――――♦――――

――――♦――――

WATER FOR THE SUMMIT

IN addition to

the many construction problems facing James Barnes and William

Jessop [1], the

Grand Junction Canal’s (GJC)

civil engineers, was that of locating sufficient water to flood the

Tring summit (the Canal’s other summit at Braunston posed less of a

problem).

During the canal carrying era, water shortages, when they occurred,

adversely affected the flow of trade and the canal company’s

revenue. But keeping a canal flooded was often no easy task,

particularly at high points along its route where obtaining

sufficient water could prove challenging. Here, the canal

engineer had to resort to various strategies: seeking a route that

avoided high ground so far as possible (which might involve

excavating tunnels, as at Braunston and Blisworth); diverting into

the canal what rivers, streams and drainage channels existed in the

locality (which often gave rise to conflict with local water

millers); and using steam-powered pumps to raise water from

low-level sources, such as reservoirs, bore holes and lower sections

of the canal itself. Maintaining a sufficient supply at the

GJC’s summit at Tring has proved a particular problem, for despite

all the usual strategies having been employed, reports of low water

levels adversely affecting trade during prolonged periods of dry

weather arose throughout the Canal’s commercial life and continue to

the present day. [2]

The Chiltern Hills, a 47 mile-long chalk escarpment, lie across the

path that the Marquis of Buckingham commissioned Barnes to survey in

1792. Confronted with this unavoidable barrier, Barnes routed

the canal through the ‘Tring Gap’, a lowering in the ridge of the

Chilterns that has been used as a crossing point since ancient

times. [3]

Taking account of the likely traffic levels across the summit and

the water requirement for lockage, it must have appeared that the

springs that rose in the Tring Gap together with local drainage were

unlikely to be sufficient and it was therefore necessary to import

supplies from further afield. As shall be seen, this task was

to present its own challenge over many years.

The Chiltern Hills are composed of chalk, some 90 million years old.

Because chalk is porous, it absorbs and stores rainwater, in effect

forming a massive underground reservoir (aquifer), which is

maintained by a stratum of impervious clay (gault) beneath it.

Natural springs appear wherever the base layers of chalk come close

to the surface. At Wendover, some 6½-miles to the west of the

Canal‘s summit pound, such a spring emerges at Wellhead, near to St.

Mary’s Church, where water from a point at which the Coombe and

Boddington hills meet wells up to the surface. This abundant

supply formed the Wendover Stream, which flowed northwards through

the valley driving numerous water mills on its way to join the River

Thame. In the absence of a sufficient supply closer to hand,

Barnes planned to divert the Wendover Stream into a channel, which

was to follow the contour eastwards along the northern face of

the Chilterns intercepting other spring-fed streams en route

[4] to join the main

line at Bulbourne [thus ― unlike its near neighbour, the

Aylesbury Arm ― the Wendover Arm is an example of a

‘contour canal’, one that by following the contour avoids the need

for locks and (for the most part) other engineering work, such as

cuttings and embankments].

|

“A meeting of the commissioners who are named in the

act, for deciding all differences or disputes between

the Company and individuals or bodies of men, began on

Monday morning last, and continued its sittings until

Wednesday, at Aylesbury; when the long existing disputes

between the Company and the Millers on the Thames River

were fully gone into. We are happy to hear, that

the Millers at the conclusion, unanimously agreed to

withdraw all claims for satisfaction, for the water of

which, they have been hitherto deprived; so satisfied

were they, that the measures adopted within this two or

three years past, on the Tring and Wendover summit level

of the Canal, will amply supply it in future, without

sensible injury to the mill-streams.” |

|

Morning Post,

30th August 1805 |

Having received authority under the 1793

GJC Act to construct whatever feeders were necessary to obtain canal

water, the Grand Junction Canal Company (GJCC) entered into

purchase negotiations with local landowners and the inevitable

water-millers to construct what at the time was to be no more than a

feeder ditch. To placate the millers, whose livelihoods would

inevitably be damaged by the diversion of the Wendover Stream, the

GJCC bought the water mills at Weston Turville and Wendover, and the

water rights to the mill at Halton, [5]

only then to find that other millers further downstream at Aylesbury

were also affected. To address this, a new reservoir was built

at Weston Turville. Eventually, the GJCC bought the Aylesbury

mills, thus avoiding the need to supply them with ‘compensation

water’.

Weston Turville reservoir lies about a mile to the north of Wendover

town centre and adjacent to the Arm. It accumulates water

mainly from two streams below the level of the canal and from any

overflow from the canal itself. Built in 1797-8, it is the

earliest and most westerly of the five reservoirs that lie along the

foot of the Chiltern escarpment. Although not intended to

supply the canal, in 1814, following several years of poor water

flow, a temporary Newcomen-type pumping engine was installed to

raise water from the reservoir as and when required. No clear

information remains as to the capacity of this pumping station, but

it is known that its outflow pipe into the canal was four inches in

diameter. Weston Turville pumping station remained in use

until about 1838, and was eventually scrapped in April 1841.

Since then water has occasionally been taken for the canal during

periods of drought, but today the reservoir is used for recreation.

Further to the east lie the four Tring Reservoirs.

They comprise Wilstone (1802,

heightened in 1811 and 1827, and extended in 1836 and 1839),

Marsworth (1806), Tringford (1816) and Startops End (1817).

Of these, Wilstone is by far the largest.

The opening of the GJC in 1800 [6] resulted

in more traffic than had been anticipated, added to which the

Aylesbury Arm (opened c. 1815) imposed a significant drain on

the main line. Consequently, the demand for water at the

summit increased. To address this, the Tring reservoirs were built

in stages to provide further supplies, which they accumulated from

local streams and any surplus from the canal itself.

The visible

remains of Whitehouses pumping station.

Originally, the reservoirs were worked by three pumping stations

located above them on the Wendover Arm; Whitehouses pumping station

(between Drayton Beauchamp and Little Tring, capacity believed to

have been 30 locks per day) worked Wilstone Reservoir, a pumping

station near Bulbourne Junction worked Marsworth Reservoir, and

Tringford pumping station (sited by Thomas Telford) worked the

Startops End and Tringford reservoirs. Each pumping station

lifted water into the Arm to flow into the main line at Bulbourne

Junction. In his Encyclopædia of Civil Engineering

(1847), Edward Cresy states that:

“. . . the principal engine at Tring is estimated as a 70

horse-power; its consumption of coals is about 1½ cwt. per hour,

with a 40 feet lift; this engine works at a pressure of 24 pounds,

makes ten strokes per minute, and pumps up sufficient for eighty

locks in 24 hours.”

Writing some years ago, Tring local

historian Bob Grace stated that:

“. . . the great reservoirs at Tring were not constructed in their

present form in the first instance. First of all they were

just ‘heads’ - the Ashwell Head at Wilstone and the Bulbourne Head

at Marsworth, which were dammed up and small pumping engines put in

to pump direct into the Wendover navigable feeder, one pump being

halfway between the main arm and New Mill and the other pump being

at the White House, above Wilstone reservoir. These were the

first engines of the neighbourhood and the men who came to work them

were, of course, engineers, the first to come into this part of the

world.

The engines were vacuum engines, which meant that they worked on

very little steam pressure (about 5 p.s.i., I think), from very

simple boilers. The engine was activated by the weight of the

pump bucket drawing up the piston and the piston cylinder being

filled with steam from this boiler, then a jet of water was squirted

in condensing the steam. The vacuum then formed drew up the

bucket and brought up the water to the canal level. These two

engines were extremely inefficient, even by the standards of those

days, and they were soon replaced by engines put in at the Tringford

station. These were two great beam engines.”

When Tringford pumping station was built in 1817, it was equipped

with a Boulton and Watt beam engine of 80 locks per day capacity, so

it is probably this engine that Cresy refers to. However, in

the period 1836-38, the Tring reservoirs were interconnected by a

system of tunnels to enable all pumping to be centred on Tringford.

A second (second-hand) steam pump (capacity unknown) — named the

‘York’ — was then installed to handle the increased load, and this

engine remained in operation until 1911 when it was replaced by

diesel-electric plant.

Following the centralisation of pumping on Tringford, the pumping

stations at Weston Turville and Whitehouses were demolished ―

Marsworth pumping station had been dismantled in 1819, as this

reservoir could then be pumped from Tringford through the new

Startopsend reservoir. Nothing remains of the pumping stations

at Weston Turville and Marsworth, but some brick foundations and

culverts on the canal bank mark the site of Whitehouses. [7]

In 1927, Tringford pumping station became wholly

electrically-driven. The original Bolton and Watt engine was

then removed – it was offered for preservation, but in the absence

of any takers it was sold for scrap – and the building

greatly altered

(and much for the worse!) including the removal of its prominent

chimney.

Above: Tringford

pumping station and stop lock, c. 1910.

Below: the beam of one of the station's steam pumping engines.

.jpg)

|

A Mirrlees 2-cylinder slow-speed diesel

engine of the type employed at Tringford

Pumping Station.

The York engine was removed in 1911 and

replaced by a diesel electric pump to work

the original deep well. A second diesel

electric pump was installed in a newly

constructed high-level well with a new

incoming heading from Tringford Reservoir

only. These pumps designated No.1 and No.2

were powered by two diesel generating sets,

one a 50hp single cylinder, and one a 100hp

twin cylinder (pictured above), supplied by

Mirrlees, Bickerton and Day. These

generators remained in use until the 1960s

when the pump motors were replaced with A.C.

motors powered by mains supply. |

In 1870, the GJCC came into legal conflict with the Tring Local

Board of Health over contamination of Tringford Reservoir and the

spread of disease:

“Part of the drainage of this town [Tring] is carried away

by a sewer which empties itself into the canal-reservoir to the

north. Before this sewer was made the reservoir received only

spring-water, a matter of some importance, as some neighbouring

villages drew their water from the stream that flows from the

reservoir. After the turning in of the sewer, in summer, when

the water in the reservoir was low, it stank abominably; and worse,

diphtheria, typhoid fever, and other such diseases, were frequent in

the villages.”

The water supply of

Buckinghamshire and of Hertfordshire by W. Whitaker (1921)

The GJCC sued for damages. They complained of the pollution

and of the additional expense incurred in pumping water up from

Tringford reservoir that would otherwise have flowed directly into

the Wendover Arm along Tring Brook. However, the Master of the

Rolls dismissed the case (with costs) on the grounds that the Board

of Health were acting in the lawful exercise of their powers.

The following year, the GJCC mounted an appeal. The Master of

the Rolls had apparently misdirected himself, for according to

The Times the GJCC were granted an injunction against the board

of Health (with costs), the Lord Chancellor ruling that “the

right of enjoyment of surface water in a flowing stream must not be

interfered with” ― public health issues did not appear to enter

into the argument! Standards of public health have of course

improved out of all measure since 1870, and today the summit pound

obtains a useful supply of cleaned water from Tring sewage works,

which is pumped into the Wendover Arm just to the east of Gamnel

Bridge.

And where does the Wendover water released from the Tring Summit

finish up? That which flows southwards along the canal

eventually reaches the Thames at Brentford. That which flows

down the sixteen locks of the Aylesbury Arm eventually enters the

River Thame, discharging into the Thames in the vicinity of

Dorchester (Oxfordshire). Water that flows northward along the

canal discharges over weirs into the Rivers Ouzel and Nene until at

Cosgrove, where the canal commences its ascent towards Braunston

Summit, it discharges into the Great Ouse, this flow eventually

reaching the Wash.

――――♦――――

An outing to Wendover by members

of the Akeman Street (Tring) Baptist Church in 1897.

Top: approaching Little Tring. Bottom: at Hare Lane bridge

(No. 8).

THE

COMMERCIAL

CANAL

IN addition

to its role as a feeder for the Tring Summit, the Wendover Arm

enjoyed a century of commercial life; indeed, on its eastern

section, shipments of grain to Tring Flour Mill continued until the

end of WWII, when road transport took over, while the adjacent Tring

Dockyard survived until 1952.

Plan of the Feeder ditch as originally conceived.

The route that was to be followed at New Mill differs considerably

from that eventually constructed.

Plan

(jpeg, 3.3MB - back arrow to return)

Although originally planned as a feeder channel, at some stage

during the land purchase negotiations the GJCC decided ― believed to

have been in response to local lobbying ― to make the feeder

navigable and thus revenue-earning. Enlarging the feeder

involved little extra cost, but its change of use did require a

further Act of Parliament. Thus, the following statutory

notice appeared in the newspapers published along the line of the

GJC, giving notice of the Company’s

intention to apply to Parliament for an Act which, among other

things, would authorise them:

“. . . . to make navigable, the cut or feeder now making, and

intended to be made, by the company of Proprietors of the Grand

Junction Canal, from the town of WENDOVER, in the said county of

Buckinghamshire, to the summit-level of the Grand Junction Canal, at

Bulbourne, in the parish of Tring, which is to pass in, to, or

through the several parishes of Wendover, Halton, Weston-Turville,

Aston-Clinton, Buckland, and Drayton-Beauchamp, in the said county

of Buckingham; and the parish of Tring; till it joins the said

summit-level at Bulbourne aforesaid. Dated this 5th day of

September, 1793.”

E. O. Gray, Aston Chaplin, Clerks to

the Company

|

|

|

Title of the 2nd GJC

Act; 34 Geo, III. C. 24 |

Reference to the “feeder now making”

illustrates that construction of the Arm commenced at an early date,

well before the main line reached Tring Summit (probably) early in

1799. The new Act (34 Geo, III. C. 24) was obtained on 24th

March, 1794, together with statutory authority to build branches to

Buckingham, Aylesbury and Saint Albans (the latter not proceeded

with).

Although the exact date of the Wendover Arm’s completion is

unknown, it was probably during 1794, for in his progress report of

May of that year, Jessop states that “About seven-eights of the

Wendover Canal is cut”, and in a GJCC circular of November,

1797, reference is made to “The Wendover collateral line, now

finished for the sake of the water”. However, as the main

line, which opened to Berkhamsted late in 1798, probably reached

Tring Summit early in 1799, trade on the Arm would not have

commenced until then. The first clear intimation that the Arm

was fully in business appears in Jackson’s Oxford Journal,

which reported that the section of the GJC from Tring to Fenny

Stratford was officially opened on 28th May, 1800.

|

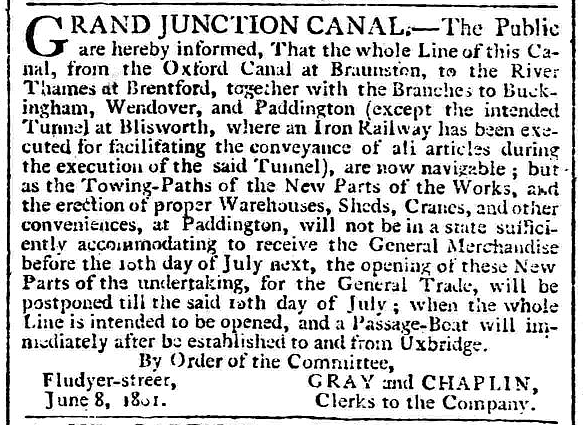

Morning Post ― announcement of the

opening of the GJC, 18th June, 1801. From the south, the GJC

probably reached Stoke Bruerne late in 1800, where a break in the

Canal (bridged by a horse-drawn railway) existed until the Blisworth

Tunnel was completed in 1805. |

For most of its working life the western section of the Arm

avoided railway competition, and until the opening of the Aylesbury

Arm (c. 1815), also carried traffic destined for Aylesbury:

“The Oxford canal, constructed under the superintendence of

Brindley, was finished in 1790, and was opened with great

rejoicings; it materially affected Aylesbury; coals and heavy goods

were brought by it to within 25 miles of the town, the intervening

distance being accomplished by road-waggons. The main supply

of coals for Aylesbury was then obtained from Oxford. In the

year 1799 the Wendover Branch of the Grand Junction Canal was

completed, which was a great advantage to this district. The

traffic in coals and heavy goods was transferred from Oxford to

Wendover Wharf, within five miles of Aylesbury.”

Buckinghamshire: A History of

Aylesbury, Robert Gibbs (1885)

‘Wendover Band of Hope’

outing at Wendover Wharf, 1889.

The narrow boat owner is Alfred Payne of Wendover.

Wendover Wharf lies a short distance to the north of the town

centre, [8] the

original access being from the end of Clay Lane across grazing land

belonging to Manor Farm. In 1796, Wharf Road was built (at

that time ending at Wendover Wharf) to give proper access to the Arm

from Aylesbury Road. Wharf Cottage, which still stands, was

the wharfinger’s residence and warehouses (long gone) were built at

the wharf opposite the tow path. It is known that grain was

landed there for milling at the great octagonal brick-built tower

mill (now converted into a beautiful private dwelling) that stands

on the opposite side of Aylesbury Road, perhaps including that

referred to in the following report:

“Philip Goodenough was indicted for stealing four bushels of

wheat, the property of Joseph Hoare. The prisoner was the

master of a barge . . . . in which a quantity of wheat was sent from

London to Wendover, consigned to Mr. Hoare . . . when this wheat

arrived at Wendover, four bushels of it were found missing.

The only evidence against the prisoner was that of a lad, named

Merchant, who had acted as his servant in the barge. He said, that

after the barge had passed Chelsea bridge, the prisoner took a spare

sack and filled it, by taking a small quantity from each of the

other sacks that were full; when the barge arrived at a place called

Harwood, on the Grand Junction Canal, a man came up and took this

sack so filled from the prisoner.”

The Times, 15th January,

1801.

Shrinkage of the sort described must have been common ― it certainly

was with coal. Hay and straw were also brought to the wharf

from the surrounding fields and shipped to London, and manure was

received in return. Slater’s Directory for 1852 lists

several coal merchants at the wharf; indeed, a correspondent writing

in the Bucks Herald in 1906 had this to say about the Wharf’s

coal trade: “Fifty or 60 years ago [c.

1850] waggons from places as far off as Lewknor and Aston Rowant

were to be seen en route through Bledlow all the way to Wendover

Wharf, for coal brought there by canal”. The wharfinger at

that time was John Bell, who offered water conveyance “To London

and forward, goods to most parts of the kingdom”.

|

|

|

Coal from Wendover Wharf – Bucks Herald, July 1841. |

There were a number of other wharfs on the Arm (App.

I.), the main ones being at Gamnel (also known as

Tring Wharf) and at Buckland to the south of Aston Clinton. A

trade directory listing of 1854 suggests that Buckland wharf was

managed by the landlord of the adjacent New Inn, whose other listed

activities were “coal merchant and collector of taxes”.

A pair of Alfred

Payne (Wendover) narrow boats at Buckland.

The New Inn is in the background, Buckland Gas Works was opposite

the narrow boats.

The site of Gamnel Wharf had previously been occupied by a water

mill that had been bought for its supply of water and dismantled by

the GJCC. The first reference to the Wharf itself occurs in the GJCC

Minutes. On 14th October 1800, a wharf at Tring (presumably Gamnel

Wharf) was auctioned for three years from 29th September. It was

taken by James Tate, a coal merchant, for £15 per annum (the Company

Minutes for this period also record that the fishing rights for most

of the Wendover Arm were let in June 1800 to Acton Chaplain, the

GJCC’s Clerk, for twenty one years, at £2 10s a mile). A deed

of transfer records that on 5th July, 1810, the GJCC sold to William

Grover, for £400, “all that wharf land and buildings thereon

containing one acre and three roods more or less situate next Gamnel

Bridge in the Parish of Tring.” Grover must have seen a

business opportunity to continue the milling previously done on the

site, but by wind power; the tower mill that he erected at Gamnel

became the seed from which eventually grew Heygates Mill, the large

flour-milling complex that occupies the site today.

Gamnel Wharf windmill ( built c.

1812, pulled down in 1911) and steam mill (built 1875) ― note the

lightening boat in the foreground.

Mr. & Mrs. Ward, daughter Phoebe and

her family from Startops End,

discharging Manitoba wheat at Tring Flour Mills c. 1930s.

The 50th

birthday celebration for William Mead (owner of Tring Flour Mills -

background) in 1918, during which

he entertained wounded soldiers and airmen from RAF Halton Camp

hospital, near Wendover.

The narrow boat Victoria is registered to Frederick Mead of

Paddington.

Grover was also active as a canal carrier, his listing in Pigot’s

trade directory for 1839 advertising “To London and all places on

the line of the Grand Junction Canal, and goods forwarded to all

other parts of the Kingdom, by Grover and Son, from Gamnel wharf,

and Thomas Landon, from Cow Roast wharf, daily”. Nothing

then is known of Gamnel Wharf until the business changed hands in

January 1843, when the following notice appeared in the

Bucks Advertiser:

“William Grover, in the town of Tring in the County of

Hertfordshire, having on the 28th day of January last disposed of

the business of wharfinger, coal and coke merchant and mealman, and

dealer in hay, straw, ashes, and other things, lately carried on by

him in partnership with Thomas Grover, at Tring Wharf, and at

Paddington in the County of Middlesex, under the firm of ‘WILLIAM

GROVER & SON’ to his sons-in-law, William Mead and Richard Bailey.

Messrs. Mead and Bailey beg to announce that they will continue to

carry on the same business, upon the said premises, in partnership

under the name of ‘MEAD & BAILEY’. All debts due to and owing from

the said William Grover, will be received and paid by Mead &

Bailey.”

Bucks Advertiser,

January 1843.

The notice gives a good indication of the nature of the business

carried out, not just at Gamnel Wharf, but at Wendover and at many

wharfs in rural locations at that time.

|

|

|

Transhipping grain from lighter to narrow boat

at Brentford. |

Mead and Bailey continued to offer a diverse range of

services, later advertising themselves as millers, coal merchants, wharfingers,

and water carriers. [9] A

few years later the partners advertised London horse manure (mountains of it

were generated in the horse-powered Metropolis of that age), which they shipped

by canal from their wharfs at Paddington. Paddington Basin was also the

scene of another William Mead & Co. activity, that of transporting by canal

London’s rubbish for disposal in worked-out gravel and sand pits, and at nearby

brick-yards (which recycled the cinders) ― a magazine article (App.

II.) written in 1879 describes both

the early use of electric light for illuminating the refuse wharfs and the

unsavoury nature of Mead’s rubbish disposal business. Shipments of

imported grain were also delivered to Mead’s flour mill at Tring by canal from

the London docks via Brentford, where the grain was transhipped from lighters to

narrow boats for its journey up the GJC. Grain shipments to the mill

continued until the end of World War II, when road haulage took over.

In addition to the commercial wharfs on the Arm, there were two small canal-side

gas works, which supplied town gas to the Rothschild mansions at Aston Clinton

and at Halton. Wendover Gas, Coke & Light Company was also located near

the Wendover canal wharf. The close proximity of these plants to the Arm

suggests that they received supplies of coal by narrow boat and might also have

exported the by-products of the town gas manufacturing process (coke, coal tar,

sulphur and ammonia) by this means.

The last business to use the Arm was Bushell Brothers, a firm that over the

years built and repaired a wide range of craft including canal barges of various

types, pleasure boats, maintenance flats, tugs and a pair of fire floats for

John Dickinson’s paper mills. The firm ceased trading when the brothers

retired in 1952, although by then the boat trade had diminished and the firm

were building bodies for a range of commercial motor vehicles.

Bushell Bros. boatyard (Tring

Dockyard) ― Tring Flour Mill to the rear.

Reproduced by kind permission of Miss Catherine Bushell.

Tug ‘Bess’

under construction at Tring Dockyard, 1921.

At 75ft x 14ft 6ins x 5ft 6ins draught, her size was such she could

only just pass along the Canal to London.

Reproduced by kind permission of Miss Catherine Bushell.

――――♦――――

|

|

|

|

Canal-side

trouble at Buckland Wharf.

Bucks Herald, 27th September 1884. |

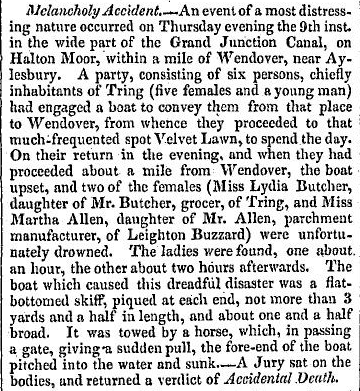

Melancholy

Accident

at Halton Moor.

Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 18th September 1824 |

Sunday school outing

about to depart from Gamnel Wharf, 1931.

Reproduced by kind permission of Miss Catherine Bushell.

――――♦――――

LEAKAGE AND

PARTIAL CLOSURE

CONSTRUCTION of

the Wendover Arm started soon after the 1793 Act had been obtained,

for in a report submitted in May 1794, Jessop informs the Board that

the Arm was almost complete, but not yet flooded. From the

outset it appears that he knew that the chalk terrain over which

part of the Arm was to pass would prove difficult and that leakage

might be a problem:

“About seven-eights of the Wendover Canal is cut, — the remainder

having corn on the ground, will rest till after harvest; in the mean

time what is done will be gradually tried with Water, for much of

the ground in this line is very leaky, and must be lined with Earth,

and be saturated with muddy Water: the rule that has been generally

observed — of avoiding plain cutting until necessity calls for it,

has a reasonable exception in this case, for by exposing it to the

changes of Weather, and particularly to Frost, the Chalk will

dissolve into a pulpy substance, and facilitate the operation of

Puddling.”

William Jessop, London, 27th May

1794.

The first reported leakage was in 1802, and in the following year

the Arm was closed for some months for remedial work. This was

carried out under the supervision of the canal engineer Benjamin

Bevan, who during the project procured more water for the Arm at

Wendover (App. III.)

and submitted his proposal for what was to become Marsworth

Reservoir. When the civil engineer Thomas Telford inspected

the GJC in 1805, his report picked up on Jessop’s concern, expressed

a decade earlier, about leakage on the Arm:

“A great proportion of the Wendover Branch is cut through loose

chalk; and Mr. Bevan appears to have laboured with much activity and

zeal to render the whole watertight: in this he has partly

succeeded; but much perseverance is requisite to make this important

part of the canal perfectly secure; the lining with clay must be

continued, and the banks must, in several instance, be made stronger

and higher. As much depends upon the perfection of this summit

I cannot help strongly recommending that every attention be paid to

it.”

Report on the General State of

the Grand Junction Canal, Thomas Telford, May 1805.

Further problems with leakage occurred for the remainder of the

Arm’s working life, the costs of significant repairs being announced

periodically in newspaper reports of the Company’s Annual General

Meetings. In 1855, the Arm was closed due to leakage, but on

this occasion repair was effected using a new form of lining,

asphalt, in place of the traditional puddle clay. This was

applied to the section of the Canal between Little Tring and Aston

Clinton and although it stemmed the leakage to some extent, it

became damaged by a combination of earth movement, by canal boats

brushing against it and through the use of poles. (App.

IV.) By 1897, the leakage had reached such an

extent that the Arm was drawing water from the main line. This

led to the Canal being dammed at Little Tring, where much of the

stop lock (built c. 1901) remains.

A number of schemes were then considered for restoring navigation

or, as an alternative, reverting the Arm to its original role as a

feeder. With the arrival of the Metropolitan Railway at

Wendover in September, 1892, the commercial future of the Arm must

have looked bleak, added to which the numerous attempts to stop

leakage over the years had proved expensive and unsuccessful.

These factors probably influenced the GJCC’s decision to abandon the

Arm as a navigable waterway west of Little Tring. However, the

closure was contested in the High Court, where their Lordships,

sitting as the Railway and Canal Commission, ruled unanimously in

favour of the GJCC, the gist of their argument being that the

Company was under no legal obligation to maintain the Arm as a

navigable waterway, and at any rate the economics of so doing would

have been prohibitive (the legal costs of the case would probably

have paid for the Arm to be repaired!).

The report of the case (brought by Lord Rothschild, Lady de

Rothschild and Mr Alfred de Rothschild) in

The Times also provides some interesting information on the

level of traffic on the Arm during its final years of commercial

operation:

“The earning, which at one period yielded a good profit, had been

on the decline for some time before 1898. In 1883, the number

of tons carried was 12,800, but the tonnage fell to 4,800 tons in

1893, 2,600 in 1894, and to less than 2,000 in 1896-7; and the

decrease in the receipts from tolls was from £1,100 in 1883 to £423

in 1893, and to about £200 between 1893 and 1898. One reason

of the traffic falling off was in 1894 the Metropolitan Railway was

opened to Wendover [reported elsewhere as Sept., 1892], and

from that time the Wendover traffic in coals was transferred from

the canal to the railway. On the other hand it is estimated

that the sum, that would have been expended on the part of the canal

at present closed, before it could again be used as a navigable cut,

would not be less than £22,000. The ground on which the canal

is constructed is chalk, and the necessity of preventing the loss of

water from the porousness of the chalk accounts for a large part of

the £22,000.”

Rothschild and others vs. the

GJCC, The Times, 9th May, 1904.

The Arm was finally abandoned as a navigable waterway west of Little

Tring in 1904, although for some years before (probably since at

least 1897) it had only been in intermittent use. However, as

late as 1906, an appeal (typical of those that were to arise during

the branch-line closures of the Beeching era) was made to the

newly-convened Royal Commission on Canals to bring pressure on the

GJCC to reopen the Arm to navigation:

“. . . . With capable handling, however, the Canal could be made

to hold water effectively, and at no unreasonable cost. The

following figures represent part of the traffic in the year 1897,

immediately before the canal was closed:

Manure ― 500 tons were sent to Wendover, and 120 tons to Buckland

Wharf;

Hay and straw ― 350 tons were sent from Wendover, and 150 tons from

Buckland Wharf.

This represents part of the traffic when the Canal was only half

full of water, and boats had a difficulty in getting along partially

laden . . . . In many ways those living in the parts of the counties

served by the two branches are injuriously affected. By

increased cost of carriage of goods, equal to 2s. per ton to the

nearest railway Station. By inability to obtain manure for

farmers at a reasonable cost. By wear and tear of roads

through having to cart goods and coal which ought to come by water.

By having to cart hay, straw and cereals to the Railway Stations,

which represents 2s. in the ton extra cost to the farmers, and a

reduced rental to the landowners, besides extra rates to the general

public to cover wear and tear on the roads . . . .”

Bucks Herald, 2nd

November, 1906.

It is interesting to note the Arm’s importance to its local farming

community. Reference to it being “half full of water”

refers to the use of stop planks to block off the Arm prior to

construction of the Little Tring stop lock (c. 1901).

It appears that, as early as 1891, boats navigating the Arm to the

west of Little Tring had first to be lightened to reduce their draft

on account of its shallow water:

“The Clerk [to the Council] had also received a letter

from Mr Thomas Mead, of the [Tring] Flour Mills, complaining

that boats bearing dung [were] lightening their loads (for

the purpose of entering the shallow water of the Wendover Arm) near

their mills, and he wished the practice, if the matter came under

the jurisdiction of the Board, to be stopped. ― Mr Clarke

corroborated the facts of the complaint. ― Mr Baines [the

Council’s surveyor]

said that he had been to the spot, and told the boatmen that the

practice must be stopped, and that they must lighten elsewhere.

They asked him to allow them to lighten in the middle of the night,

and he gave permission for this to be done.”

Bucks Herald, 4th July,

1891.

Following closure, the section between Wendover and Drayton

Beauchamp was relined, the water level lowered and the flow from

Wendover diverted into Wilstone Reservoir. This scheme was

later changed, the water being channelled from Drayton Beauchamp

direct to Tringford pumping station through a pipeline laid along

the canal bed.

The much

disfigured Tringford pumping station in the late 1960s ― the Arm was

then being used as a

dump for redundant narrow boats. Note the condition of the tow

path!

――――♦――――

RESTORATION

THE formidable

project of restoring the Wendover Arm to a navigable waterway beyond

Little Tring is being undertaken by members of the

Wendover Arm Trust. The Trust is a charitable body

formed in 1989 with the aim of restoring and promoting the Canal.

Its membership ranges from organisations with a specific interest

(such as the environment) to individuals who support the aims of

restoration in general. The Trust does not own the Canal; it

is owned by The Waterways Trust, who work closely with the Trust on

planning and undertaking its restoration, and are represented on the

Trust’s Board.

The engineering problems in restoring the Arm are believed to be

relatively straightforward, although the solutions are expected to

be expensive, with funding being a major obstacle. At the time

of writing, progress has been slow but significant.

Although some work had been completed earlier, the first phase of

the planned restoration was completed in March 2005. It

comprised the refurbishment of the stop lock at Little Tring; the

replacement of a road embankment across the canal bed at Little

Tring with a concrete road bridge, built to a traditional design and

faced with bricks to provide an authentic appearance; construction

of a winding basin at the terminus to allow boats to turn; and the

reinstatement of about ¼ mile of canal.

The second phase (expected completion in 2016) involves restoring to

navigation the section between Little Tring and an isolated section

of restored and re-watered canal to the west of Drayton Beauchamp.

The latter was constructed during the building of the Aston Clinton

Bypass in 2003, [10]

and involved a slight realignment of the Arm to provide navigable

headroom under the new bypass road bridge. Restoring the phase

2 section includes re-profiling the Canal to its original shape and

lining its sloping sides with concrete blocks on top of waterproof

Bentomat© lining [11].

Two new timber footbridges have already been erected to enable the

Canal to be crossed safely, and reinforced concrete covers are being

laid over the 100-year old buried pipeline to prevent any subsidence

should it collapse.

.JPG)

Relining the Wendover Arm - the upper

part of the Bentomat liner, visible above the protective blocks, is

about to be covered with turf.

At the canal bed, the liner is covered with 300mm of earth.

The main obstructions to be met during Phase 3 concern bridge

restrictions, these being the accommodation bridge at Buckland

Wharf, the ex-A41 road bridge and the lowered Halton Village Bridge.

The restoration of this section is technically feasible but

expensive.

――――♦――――

RECREATION,

SPORT ― AND

ALGAE

ANY large expanse

of water holds a certain fascination and from their early days the

Tring Reservoirs have been sites of recreation. Walking and

fishing provide much enjoyment, but at the head of the list must

come interest in wildlife. In recognition of this, the

reservoirs were designated a National Nature Reserve in 1955; in

1987, they were redesignated a

Site of Special Scientific Interest

on account of their wealth of wildlife, particularly birdlife.

Because there are few natural lakes in Southern England, the

reservoirs provide an important haven for wintering water birds.

Weston Turville Reservoir is outside this group. Although it

continues to be owned by

The Waterways Trust, it is no longer

used to supply canal water. Managed by the

Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire

Wildlife Trust, it too is recognised as an important nature

reserve while at the same time providing an expanse of water for the

enjoyment of members of the

Aylesbury Sailing Club, a nice mix of uses.

Somewhat at odds with the above, for 130 years the sporting rights

to the reservoirs were retained by the landowners of the Tring Park

Estate, who arranged shooting parties for their distinguished

guests, which included on one notable occasion King Edward VII.

Until recent times the owners were entitled to shoot on up to six

days per year, their quarry being captive-bred mallards reared on

Marsworth reservoir and the smallest of the reservoirs at Wilstone.

A gamekeeper employed by the Estate also managed the three

reservoirs stocked with coarse fish and the fourth with trout.

From April 2008 British Waterways acquired both the fishing and

shooting rights, of which the latter has now been discontinued.

As for swimming, during the first decades of the 20thC this was a

popular pastime and organised swimming galas were a regular fixture.

They were probably supervised and safe enough, but the general

practice was eventually banned due to several fatalities caused by

swimmers becoming entangled in water weed.

Swimming lessons,

Wilstone Reservoir in the 1930s.

Prolonged dry spells, when the water levels fall drastically, cause

deep cracks in the reservoir beds and the growth of a toxic

phenomenon,

Blue-green Algae (Cyanobacteria).

These algae grow so rapidly they are difficult to control and can

produce toxins that are dangerous to humans as well as to animals

and marine life in general. Although susceptible to

herbicides, the problem can also be addressed with the use of barley

straw, which, in a complex chemical action, inhibits their spread.

Each of the reservoirs except Tringford, which is not affected, is

now strung with lines to which barley-straw mattresses are attached.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX I.

THE WHARVES.

TODAY it is

difficult to imagine that during the canal carrying era ― and

particularly before the onslaught of the railways (c. 1840s)

wiped out many of our canals (vide, for example, the fates of

the Kennet & Avon and the Thames & Severn canals) ― these waterways

were the trunk roads, even the motorways of their day.

Communities who were lucky enough to live near a canal route saw the

prices of coal, timber, building materials and even food fall

dramatically when the canal came to town. Those in rural areas

especially found a cheaper and quicker route to market for their

farm produce; there is much evidence, for example, that the Wendover

Arm was used to export hay and straw to the horse-powered

Metropolis, where it was converted into horse dung (manure) and

shipped back by canal for use as an agricultural fertiliser.

Although it was never particularly common, even humans travelled by

canal:

Passengers by

canal on the Paddington branch of the GJC.

It is recorded that the poor left Aylesbury by barge on the first

stage of their journey in search of a better life in the colonies or

the New World, while newspaper reports of troop movements by canal

were quite common before the railway age:

The Morning Post, 5th

December, 1821

Indeed, the military even constructed a large barracks and

arsenal adjacent to the GJC at Weedon, and into which Barnes built a

short branch canal that entered the walled site through a

portcullis.

Much cargo-handling on the Wendover Arm was probably carried out by

boatmen drawing up their craft adjacent to a farmer’s field, and

loading/discharging over planks between the boat and the bank. Where

an accommodation bridge was conveniently placed, it would probably

have been easier to moor under the bridge and transfer goods over

the parapet. But there is archaeological evidence of other

wharfs on the Arm in addition to those generally known about.

Research carried out by Barry Martin suggests there were wharfs of

some type at the following locations (moving upstream from Bulbourne

Junction):

-

on the right

(non-towpath side), a few hundred yards above the overspill

weir, was the wharf edging for the Marsworth Engine/Pump;

-

on the left bank

just before Gamnel Bridge (bridge 2) there is evidence of a

wharf;

-

above Gamnel Bridge

wharves associated with the various mills and the boatyard;

-

further upstream,

beyond the Tring Feeder, there was a small wharf on the

off-side, its edging being visible during wintertime when the

foliage recedes. Local recollection is that it was a coal wharf;

-

the wharf edging

associated with bringing coal supplies to the Tringford pumping

station remains in place;

-

the next definite

wharf edging was for the Wilstone (Whitehouses)

pumping station;

-

just before Drayton

Bridge (bridge 5) there was a brick wharf, on the off-side,

adjoining Bridge Farm. This was certainly very evident when the

first undergrowth clearance was done in about 1977, but when BW

restored this section of canal the wharf was demolished;

-

next upstream was

the wharf behind the New Inn, then beyond bridge 6 (the old A41)

there was the wharfage for the Buckland Gas Works;

-

upstream of the

Stable Lane (Wellonhead) Bridge (bridge 7) there was a further

slewing ridge which provided access from the Aston Clinton House

to the towpath side; although this is the site of the “concreted

narrows”, a brick-fronted wharf was visible a few years ago;

-

if there were

wharves at Halton, in the area of the now lowered road bridge,

they would have disappeared during the construction of that

bridge;

-

on the off-side,

about 200 yards further on, there is another small brick-fronted

wharf which may have been associated with the Dashwood estate.

An old map (see

fig. ‘5’ at

Halton) of the area shows that the Canal was widened locally and

there was a boathouse;

-

just before Perch

Bridge, the Halton Gasworks would have had a wharf on the

off-side. Working boats were also known to have moored

upstream of Perch Bridge (out of site of Sir John’s residence)

and their crews visited the nearby Perch Inn, but there

probably wasn’t a wharf at this location.

-

the final wharf was

probably that at Wendover, of which very little remains today

other than the name, Wharf Road, and the wharfinger’s house.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX II.

FILTHY LUCRE

From GOOD WORDS

(Volume 20, 1879)

by

CHARLES CAMDEN.

I HAVE chosen my

title with reference to the nature of the materials from which the

gain of which I have to speak is extracted — very fertile “farms of

two acres,” some of our dingy dust yards prove — not with the

slightest to the character of the extractors. Through the courtesy

of Messrs. W. Mead and Co, I have been allowed to pay a visit or two

to a “contractor’s yard,” which claims to be the largest, at any

rate to do the largest business, in London. It is one of

several bordering the Paddington Basin, which from that circumstance

might be called, by a trade pun, a “slop” basin.

Most of the London dust-yards are at the water-side, for the sake of

the water carriage which the canal or river gives them for their

dust and cinders to the country brick makers.

In Messrs. Mead and Co.’s yard, the electric light is used after

dusk in winter, to enable the men to go on with the loading of the

barges. Wandering along the muddy North Wharf Road, with its

dozens of empty tumbrils resting with their shafts up in the air, or

crossing the canal and railway bridges in Bishop’s Road, you catch

sight of an aurora in the sky, and on entering the yard you see a

big meteor star, pulsing white and bluish white, suspended in

solitary brightness over the black heaps from which the weary

sifters have gone home to rest, weirdly lighting up the men plying

pick and shovel down by the canal, and making part of the sluggish

water seem to be phosphorescently afire. As far at the

influence of the light extends, the separate stones can be

distinguished on the gravel wharf, and within that circle the

lamp-posts and the buildings of the yard stand out clear as by

daylight, or rather clearer, since the mysterious brilliance seems

to purge them of their grime. But all gas-jets are turned into

mere faint bilious blotches and outside the magic circle the

darkness, both on land and water, is intensified into ebon gloom.

And now for the daylight aspect of the yard, or rather yards.

An apology for untidiness on a contractor’s premises has a somewhat

droll sound, but one is made for the “muddle” in which the

“slop-yard” is found. The slop is just thawing after long

frost. A wide mass of dark, very unappetising batter-pudding

is pent up on the wharf, waiting for a barge to come alongside; when

a trap will be opened and the unsavoury mess cascade in a mudfall.

This accumulation of scavenging is indiscriminately called slop, but

formerly street dirt dirt used to be divided into mud and “mac,” the

latter being the product of traffic friction on macadamised roads,

and the more valuable for builders purposes because freer from

manure than mud. When I asked my obliging guide at what rate

the yard sold its slop, I was astonished to hear, “We get nothing,

give it away to brick-makers fifteen or sixteen miles down the

canal. Yes, the cost of the carriage falls on us too. We

own twenty barges, with two men and a horse apiece, and we hire as

well. The brick-makers know that we must get rid of the slop,

and so they won’t give us anything for it. If” he added, “the

yard were close to a country district, so that farmers could come

with their carts, they would be glad enough to pay us for it, it

makes excellent manure.”

Separate from the slop wharf by the gravel wharf, which, from its

contrast to its neighbours on both sides looks strangely clean and

almost goldenly bright, is the dust-yard. Outside the gates

empty dust and mud carts, so thickly furred with mud and dust that

the owners’ names are often almost illegible, are congregated in the

manner I have described. Other carts are rolling out empty and

rolling in full. One of them unfortunately goes over a poor

follow, who is taken up tenderly by two brother dusties and lifted

with care into a cab, backed into the yard to receive him, and in

this he is carried off to hospital in charge of a clerk.

The firm owns a hundred and twenty horses, manifestly well fed, and

they are well housed also. In their stables under the granary

which contains their hay, straw, chaff, and crushed oats, hot as

well as cold water is laid on for use at night. Their drivers

look as if they would be all the better for similar accommodation.

The dust that thickly covers the tracks in the yard is much like

that one flounders through in iron-works. Here the foot sinks

over the ankle in dry, black powder, and there sticks fast in

viscous, blacking-like mud. Even on a winter afternoon, with

the mercury dropping to freezing point, the perfumes floating, or,

rather brooding in the atmosphere are not those of Araby the Blest.

On a sweltering summer day, after a shower, what must be the odours

steaming up from such a conglomeration of ashes, egg-shells,

oyster-shells, herring-heads, greasy rags and bones, old boots and

shoes, and miscellaneous rubbish! And yet the people employed

in the yard, both men and women — so far as their flesh can be made

out through the dirt with which they have peppered and besmeared it

— look healthy, some quite plump and ruddy; and the same may be said

of the men who go out with the dust carts and the scavengers.

Paddington Basin

today.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX III.

OBTAINING A WATER SUPPLY FROM WENDOVER

(From “On the Utility, Structure and Management of

Canals” by Joseph Townsend: published in

The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and

Pleasure, Vol. XX, July-Dec 1813.)

MOST canals are

distressed for want of water, because either they are above the

springs, or they are not permitted to derive a supply from mill

streams. A knowledge of geology will, in most situations,

relieve the engineer from distress, and teach him distinctly to what

distance he must drive a level, or to what depth he must sink his

shaft, that he may find ample supplies of water, such as no one can

claim, because they nowhere break out in springs, till they issue

either into the narrow seas, at the bottom of the ocean, or in the

great abyss. . . .

It was this knowledge, derived from Wm. Smith, which enabled Mr.

Bevan to direct his shaft into the chalk hills at Tring, by which he

secured a supply of water for the Grand Junction Canal. . . .

In Dr. Rees’s

New Cyclopedia we have a very interesting account of the manner

in which Mr. Bevan supplied a part of the Grand Junction Canal with

water. This ingenious artist discovered, that on the north

side of the chalk summit between Tring and Wendover, different

water-tight beds in the lower chalk held up springs a considerable

height above the canal, and, in order to avail himself of these, he

began a tunnel in the upper bank of the canal near Wendover, which

he drove half a mile southward to intercept the springs in their

descent. But observing that the principal of this water was in

the winter and spring months, when the other sources were more than

sufficient for the supply of the canal, he placed a strong

water-tight valve in the most favourable part of his tunnel, which

as soon in the autumn as the canal is amply supplied from its other

feeds, he keeps shut until these begin to slacken in their supply.

The water in the immense planes of these beds of chalk accumulate,

as in a vast subterranean reservoir, the springs rise to the level

to which they originally rose, before this tunnel was begun, that

is, twenty feet above the canal, and for many weeks after the

opening of the valve in the beginning of summer they pour forth a

most surprising stream of water into the canal, which otherwise

would have found a vent miles off in the chalk vallies, or have

slowly made its way down through the joints and fissures in the

strata, to springs which issue at the bottom of the chalk below the

level of the canal.

Had the Grand Junction, like the Kennet and Avon canal, been cut to

the south-east of the chalk hills instead of being on the north

side, as it is near Wendover, and had this canal been formed in a

bed consisting of chalk rubble and of flinty gravel, Mr. Bevan would

have had no need of penning up his chalk feeders in the autumn, in

the winter, and in the spring. Of this we can have no doubt,

when we take a view of that immense quantity of water, which flows

in the thick bed of gravel, far beneath the surface, all the way

down the valley from Crofton, Bedwin, and Hungerford, to Kintbury,

Newbury, and Reading.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX IV.

THE CAUSES OF LEAKAGE AND THE ASPHALT LINING

The following text draws on research undertaken by

Barry Martin and Professor Timothy Peters

THE Wendover Arm

and the Llangollen Canal were the only significant canals built with

the primary purpose of supplying water, in the case of the latter,

to the central section of the Ellesmere Canal. It is

coincidental that they are also the only known canals where asphalt

lining was used, although in the case of the Llangollen Canal it was

only to effect a small repair.

From the outset if was realised that the ground over which the

Wendover Arm was built would prove troublesome and, as outlined

above, leakage soon became a problem that was to prove intractable

in the long term. There were probably two reasons for it:

• the porous nature of the ground through which the Arm was cut

meant that it had to be lined, and there is evidence to suggest that

this was not done properly. The original puddle clay was

sub-standard, having been excavated during the construction of Tring

Cutting and used because it was cheap and readily available.

Commercial pressure to keep the Arm open left insufficient time for

relining to be completed properly, while recent analysis of the

asphalt lining put down in 1856-7 revealed it was poorly laid and

not to the specified thickness;

• probably a more important reason is that the canal bed was roughly

on the level of several ‘seasonal springs’, which from time to time

punctured its lining. With the low rainfall experienced in

recent years it is now believed that the water table has fallen

considerably and that this problem ought not affect the restoration

work now being carried out.

In 1856, the Wendover Arm was again losing water and John Lake, the

GJCC’s Engineer, visited some

reservoirs (locations unknown) to inspect their use of asphalt as a

liner. His conclusion – supported by Sir William Cubitt, the

Company’s consulting civil

engineer – was that it would be far cheaper to repair the Arm using

asphalt (£4,470) as against puddle clay (£12,500). On this

basis it was decided initially to apply a two inch thick lining of

asphalt to the section of the Arm between Little Tring Bridge and

the Wilstone Swing Bridge (¾mile ― the

swing bridge has

long since gone).

The asphalt mix that was used comprised one part of coal tar, one

part of crushed limestone, one part of sand and some coal oil.

The sand was readily available from Leighton Buzzard, the limestone

from local sources and John Bethell, owner of the Greenwich Gas

Works (now the site of the Millennium Dome), was to supply 2,000

tons of coal tar at 10 shillings and 6 pence per ton, and 6,000

gallons of coal oil at 4 pence per gallon (records indicate that he

was unable to supply more than 1,500 tons of coal tar, while other

records show that considerable less actually arrived at Little

Tring).

In June 1857, the Committee reported that the trial length of lining

was satisfactory and that it should be extended further up-stream.

By the time the asphalting had reached Drayton Beauchamp, the mix

had changed; the limestone had been replaced by crushed chalk and no

coal oil was being used, while a recent analysis of a sample taken

near Drayton Beauchamp revealed the presence of crushed coke (coke

is a by-product in the production of town gas, and might have come

from the nearby Buckland Gas Works). On March 21st 1857, Sir

William Cubitt tested and reported favourably on the quality of the

asphalt.

In application, the asphalt was prepared in situ by crushing

and mixing the ingredients, which were then heated in flat pans over

braziers and poured and spread while still workable. However,

recent excavations have revealed that, in general, the applied

thickness of the asphalt lining was one inch as opposed to the two

inches specified, while it did not extend above normal water level

on the canal banks! Only a few small examples of asphalt

lining have been discovered whose thickness exceed one inch –

notably a nine inch thick section on the tow-path side of the canal

bed near bridge No.4, which is thought might be a repair. The

GJCC Minutes record a quantity of surplus coal tar being sold off.

On May 13th 1858, Lake tested for leakage over a 3,828 yards section

and recorded a rate of 1½ locks per day compared to 15 locks per day

before relining. GJCC records indicate that the asphalt

repairs were initially considered successful, but after 12 years the

Arm was again experiencing leakage, the integrity of the lining

probably have being affected by several causes including an

excessively rich lining mixture, poor construction practice, and

damage from boats, ice breaking and earth movements. Recent

excavations have also revealed that the existing clay puddle was

removed prior to the asphalt being laid, and that it received no

protection afterwards (the current restoration practice includes

putting down a considerable layer of earth ― 300 mm ― on top the

Bentomat liner in the bed, concrete blocks over the lining on the

banks up to water level, and turf above).

.jpg)

The former Whitehouses swing

bridge c. 1896.

Reproduced by kind permission of Mike Bass.

Below, the same bridge after the Arm had

been abandoned -

Marsworth Reservoir in the background.

――――♦――――

FOOTNOTES |