|

THE GRAND JUNCTION CANAL

A HIGHWAY

LAID WITH

WATER.

THE PARLIAMENTARY HURDLE

PRIVATE ACTS OF PARLIAMENT

Before the ceremony of ‘cutting the first sod’ could take place,

those proposing a new canal scheme often found themselves

involved in a lengthy and expensive legal wrangle. This

stemmed from the need to obtain a ‘private’ Act of Parliament,

which was necessary to authorise the canal’s construction (and

all which that entails) together with aspects of its operation,

such as the toll to be charged on the passage along the waterway

of various types of goods (the total cost of conveying goods

comprised the toll ― the charge for using the waterway,

generally governed by its Act ― to which had then to be added

the canal carrier’s charge).

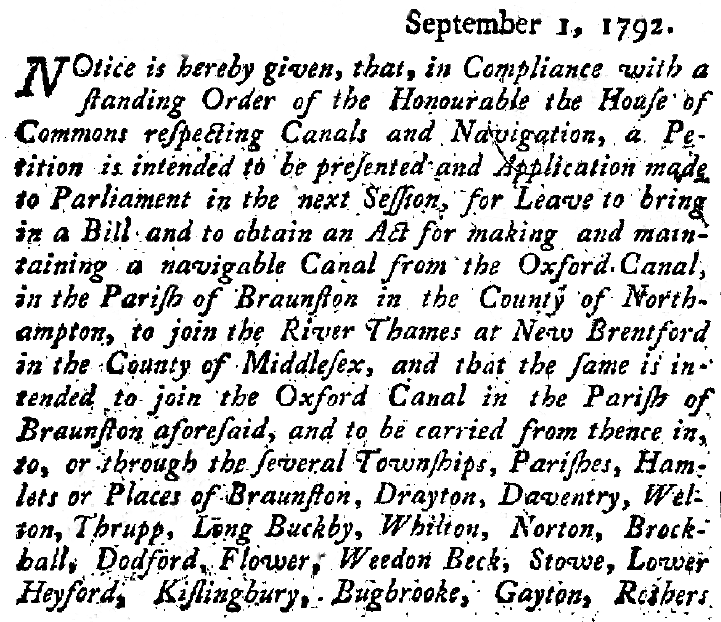

Start of the statutory notice

appearing in the London Gazette, giving notice of an

application to Parliament for a private Act to build and operate

the Grand Junction Canal.

A draft Act of Parliament is known as a Bill, and it was not

unusual for a canal (and later railway) Bill to meet with strong

opposition in part or in parcel when presented to Parliament.

Unlike ‘public’ Bills, which apply to everyone within their

jurisdiction, a ‘private Bill’ [1] is a

proposal for a law that applies only to a particular individual,

group of individuals, or a corporate body, such as a local

authority or public company. If the Bill is approved by

Parliament it then becomes a private Act (of Parliament).

The privileges granted by a private Act might include relief

from another law, or a unique benefit, or powers not available

under the general law, or relief from the legal responsibility

for some otherwise wrongful act.

Where a canal was to built, a private Act was necessary if the

capital to construct it was to be raised by creating a joint

stock company ― if effect, by public subscription ― or its

course lay across public land and that of individuals not

associated with the scheme (unless they had given their consent,

a area of law known as ‘wayleave’, often applied to early

colliery railways). There were two reasons for this.

First, under the cumbersome law of the day, joint-stock

companies could only be set up by royal charter or a private Act

of Parliament. [2] Furthermore, an Act of

Parliament was necessary to authorise a scheme to proceed in

accordance with specific provisions not otherwise available

under the law ― for example, a provision generally to be found

in a private canal (or railway) Act gave the proprietors the

legal power to acquire specified private land by compulsory

purchase, in effect, to acquire it without the owner’s consent,

but with due monetary compensation. Other provisions and

stipulations might include the right to cross public highways,

divert rivers and streams, fence off towing paths, demand

payment for the use of the waterway (sometimes subject to

exemptions, such as the movement of troops) and hold General

Assemblies (shareholders’ meetings), to name just a few. The Act

would also stipulate the arbitration procedures to be applied in

cases were land values were disputed.

――――♦――――

OPPOSING THE BILL

Most of the work in examining a private Bill is undertaken by a

parliamentary committee convened for the purpose and in which

procedures follow a semi-judicial pattern. The promoter of

the Bill must prove to the committee the need for the powers

sought, and the objections of any opposing interests are heard.

Applications for private Acts were often fiercely contested, not

only by Luddites but by landowners affected by, for example,

compulsory purchase, and by businesses whose trade stood to be

damaged by the new forms of transport. During the

construction of our canals, the established river navigations ―

almost as a matter of course ― fiercely protected their

monopolies for transporting goods. The Mersey & Irwell

Navigation strongly opposed the application for a private Act to

construct the Bridgewater Canal, which they saw as infringing

their virtual monopoly of transportation between Manchester and

Liverpool. Another of James Brindley’s canals, the Trent &

Mersey, faced similar opposition from the River Weaver

Navigation, for near Anderton the planned canal was to run

parallel to the river for some distance. [3]

But occasionally landowners across whose estates a canal was to

pass actually supported the scheme . . . .

“Cassiobury Park is where we first fall in with the Grand

Junction Canal. Ready permission was granted by the present Earl

of Clarendon, and the Late Earl of Essex, to allow this great

national undertaking to pass through their respective parks; and

when we find the opposition that the late Duke of Bridgewater

was continually receiving, from parties, through whose premises

he was unavoidably often obliged to pass his navigable canals,

it must stand as a monumental record, and example of the

urbanity and amor patriæ, these distinguished noblemen exhibited

for the weal of their country.”

A Tour of the Grand Junction Canal,

John Hassell (1819)

Later, the canal companies, whose businesses then stood to be

damaged by the railways, provided formidable opposition to this

new form of transport and, as time was to show, with good cause.

From about 1840, railways began to present a threat to canals,

for they could carry more freight than the canals and far more

quickly. Take, for example, the Kennet & Avon Canal

(linking the Thames with Bristol), which suffered from the Great

Western Railway (GWR) duplicating its route and undercutting its

tariffs. In 1852, the canal company sold out to the GWR

after which the canal fell gradually into a state of

dereliction. Another example was the Wey & Arun Junction Canal,

the only canal to connect the Thames with the English Channel.

At its peak, in 1839, it carried 23,000 tons of freight.

In 1865, the railway between Guildford and Horsham opened in

direct competition, but despite the canal’s carrying charges

being cheaper, it could not compete with the railway for speed

and convenience. By 1868, traffic had virtually ceased and

in 1871 the canal was abandoned.

And so proposals for a private Act usually faced strong

opposition from several directions during the committee

hearings. Sometimes a scheme’s opponents succeeded in

their challenges, leaving the promoters with weighty lawyers’

bills and nothing to show in return. Sometimes the

promoters revised their strategy to win their cause at a

subsequent attempt, some notable examples during the

railway-building era being the Liverpool and Manchester, the

Grand Junction, and the London and Birmingham railways, all of

whose Bills were initially thrown out.

――――♦――――

THE PRELIMINARIES

As the 18th century entered the period of canal mania, and faced

with a flood of canal Bills, Parliament was forced to introduce

a set of standing orders to reduce the chaos that was building

up [4] and to give the public more information

and a greater say in their construction. The new rules,

which appeared in 1793 (Appendix),

laid down that all canal proposals should first be advertised in

the official newspaper of record (the

London Gazette) and in local newspapers along the line;

plans and sections drawn to scale were to be be deposited with

the Clerk of Parliament, Clerks of the Peace and Sheriffs along

the line; estimates of cost were to be made; a list of

subscribers was to be drawn up and also a list of affected

landowners, indicating those in favour and those not. If

anything, this increased the weight of protest by the NIMBYs,

which continues to the present day and has been demonstrated

recently in planning the route for the proposed HS2 high speed

rail link between London and Birmingham.

A new canal scheme was initially put in motion by advertisements

in the press, which to give it credibility were usually endorsed

by a number of prominent people. Advertisements would

usually be accompanied by arguments in favour of the scheme,

such as those that appeared in the local Courier during

the initial stages of the Macclesfield Canal project:

-

Goods could be conveyed by water for one quarter of the cost of

road carriage.

-

Some forty steam engines and 5,000 houses in Macclesfield were

currently supplied with coal at a cost exceeding by one third

that which it would cost if canal transport could be used.

-

Great hardship to both the rich and the poor had been caused by

the lack of a canal.

-

Material required for the manufacturing industries, imported

through the ports of London and Liverpool, would be cheaper with

canal transportation.

-

Grain, and the other staples of life, would be reduced in price,

as would timber, slate, flagg, and stone.

-

Macclesfield was at the centre of a flourishing manufacturing

district. There were other competitors so why should the

district be handicapped by the lack of a canal? This south

east part of Cheshire was also rich in freestone, lime, and

timber.

-

The Duke of Bridgewater built his canal ‘through some of the

finest estates in the country’ to foster the trade of Manchester

by connecting it with the port of Liverpool. Manchester,

at that time, was scarcely larger than Macclesfield was at this

time.

|

|

|

The Manchester Ship

Canal, Punch magazine, 1882.

The humorist’s view of the prospect of Manchester

becoming a seaport. |

If

the proposed scheme attracted a favourable reception, a steering

committee ― the provisional directors, secretary, treasurer and

solicitor ― would be elected and money then sought to meet the

initial costs surveying and of obtaining the Act. As an

inducement to part with their cash, those who contributed would

generally be given the first option of purchasing shares in the

company should the Act be obtained. [5]

The main part of a canal Act defined the route (the ‘Parliamentary

line’) that the scheme was to follow. Thus, having raised

sufficient finance and formed a committee, the next step was to

employ a civil engineer to select the best route. Until a

private Act was obtained, the civil engineer and his surveying team

had no right to trespass on private property, and permission to do

so had to be sought from the landowner. This was not always

forthcoming, and stories abound during the railway era of surveyors

carrying out their work surreptitiously at night using lamps as

markers, and of being accompanied by bodyguards ― including prize

fighters and gangs of navvies ― to protect them against violent

opposition.

However, there was little point in presenting a Bill to Parliament

if it was to face a substantial body of opposition ― especially

influential opposition ― for it would very likely result in an

expensive failure. So the next task to confront the promoters

was to mollify at least their scheme’s principal opposers with

whatever inducement was necessary to placate them, which was usually

cash. As a group, the owners of watermills were particularly

vociferous in their opposition to canal Bills, for they saw the

canal company diverting the rivers and streams on which their

livelihood depended in order to supply the canal with sufficient

water; the solution here might be for the canal company to buy them

out. [6]

But where opponents would not budge, despite a sizable carrot being

dangled before them, and especially if they were powerful in terms

of their parliamentary influence, the politically expedient course

might be to re-draw part of the route. This might result in a

longer route and/or taking on otherwise unnecessary civil

engineering work in order to bypass the obstruction, such as

building a lengthy tunnel, cutting or embankment. Such was the

case with the London & Birmingham Railway, the first Bill for which

was defeated in the House of Lords . . .

“. . . . in consequence of the opposition of a noble Earl,

half-brother to the vicar, [7] through

whose park Robert Stephenson . . . . had proposed to lead the

railway. A second Bill had been brought forward by which, at

the expense of heavy works, the park and ornamental grounds of the

Earl had been avoided, the line crossing the valley of the Colne by

an embankment of what was, in those days, of unprecedented

magnitude, and thus boring beneath the woods, at a distance from the

mansion, by an equally unprecedented tunnel of nearly a mile in

length”.

Personal Recollections of English Engineers,

F. R. Conder (1868)

Thus aristocratic opposition resulted in the high embankment to the

south of Watford Junction Station and the long tunnel about a mile

to its north, neither of which lay on Stephenson’s preferred route

for the railway.

Having selected a route, the prospectus for the proposed scheme ―

often over-optimistic in terms of its estimated capital cost,

timescale, revenue and expenditure [8] ― would

then be published in the principal daily and local newspapers:

“The document then expatiates on the inconveniences which are at

present experienced from the inadequacy of the means of

communication; and the assurance is insinuated to all in whose

neighbourhood the line will pass, that it will be a boon to trade .

. . it is then duly set forth that the value of the land is either

‘moderate,’ or a comparatively ‘trifling’ item; that the whole line

with all necessary appendages, may be completed at an expense of so

many hundreds of thousands sterling; that the annual return on the

traffic arising from the conveyance of passengers and goods will

yield, at very moderate rates of tonnage, an income to be divided

amongst the subscribers ‘of at least ten per cent. per annum on

their capital,’ after paying for all charges for making the line and

keeping it in repair.”

Our Iron Roads,

Frederick S. Williams (1852)

The Prospectus informed potential investors how shares in the new

company were to be applied for ― and overwhelmed by a golden

opportunity to earn 10% net on their money, investors reached for

their cheque books. Assuming sufficient capital was pledged,

standing order documents (estimates, schedules, maps, levels, etc.)

could then be submitted, witnesses in support of the scheme lined

up, our learnèd friends consulted and briefed, and application made

to Parliament for a private Act.

――――♦――――

THE PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEE

When finally in committee, the promoters often found themselves

faced with lengthy and expensive sessions. The members of

a parliamentary committee set up to examine a canal Bill needed

to satisfy themselves that the project was feasible in both

engineering and financial terms, and that it was needed in the

area it was to serve. Also, that it did not unnecessarily

interfere with private interests or public rights and that any

harm to these was outweighed by the scheme’s likely benefits.

In examining the proposal before them, committee members asked

searching questions.

When, in 1762, the parliamentary committee set up to examine the

application to extend the Bridgewater Canal to the Mersey

questioned James Brindley, they were entertained to some

practical demonstrations. When asked to produce a drawing

of an intended aqueduct, Brindley replied that there was no plan

on paper, but he would illustrate it using a model. He

returned to the committee room with a large cheese, which he cut

into two equal parts, saying, “Here is my model.”

The two halves of the cheese represented the semicircular arches

of his bridge, and by laying over them some long rectangular

object, he showed the committee the position of the river

flowing underneath and the canal passing over it. On

another occasion, having spoken so frequently about ‘puddling’

and describing its uses and advantages, some members asked what

this mixture was that could be applied to such important

purposes. Preferring a practical demonstration to a verbal

description, Brindley had some clay brought into the

committee-room and, moulding it in its raw untempered state into

the form of a trough, he poured into it some water, which soon

leaked away. He then worked the clay up with water, to

imitate the process of puddling, and again formed it into a

trough, which held water. Brindley was also in the habit

of drawing diagrams in chalk on the committee room floor.

|

|

|

Our learnèd friends found

rich pickings. |

But

as time progressed, Brindley’s chalk and cheese approach gave way to

legal teams representing the opposing factions, who became highly

skilled in fighting their respective corners; and, as always in such

situations, the lawyers found rich pickings. Many witnesses,

whose expenses also had to be paid, were called to support or oppose

a scheme and they were cross-examined by counsel representing the

parties involved, sometimes helped along by allegedly ‘expert’

witnesses, such as Doctor Dionysius Lardner.

Despite his other talents, Lardner is remembered in history for his

disagreements in committee with the great civil engineer and railway

builder, Isambard Kingdom Brunnel (1806-59). Perhaps the most

famous of these relates to the construction of the Box Tunnel on the

London to Bristol railway. The tunnel had a 1-in-100 gradient.

Lardner asserted that if a train’s brakes failed in the tunnel, it

would accelerate to over 120 m.p.h., at which speed the passengers

would suffocate. Brunel pointed out to the committee the basic

error in Lardner’s calculation, his total disregard of

air-resistance and friction.

But the outcome of such exchanges was that many project promoters

failed to convince the committee, and their Bill was defeated.

Some Bills that failed at their first attempt subsequently

reappeared, that for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway being one

such case. At the first hearing of this Bill in 1824, the

line’s Engineer, George Stephenson, failed to provide the committee

with adequate explanations about the scheme’s engineering aspects:

“Thus ended this memorable contest, which had extended over two

months ― carried on throughout with great pertinacity and skill,

especially on the part of the opposition, who left no stone unturned

to defeat the measure. The want of a new line of communication

between Liverpool and Manchester had been clearly proved; but the

engineering evidence in support of the proposed railway having been

thrown almost entirely upon George Stephenson, who fought this, the

most important part of the battle, single-handed, was not brought

out so clearly as it would have been had he secured more efficient

engineering assistance, which he was not able to do, as all the

engineers of eminence of that day were against the locomotive

railway. The obstacles thrown in the way of the survey by the

land-owners and canal companies, by which the plans were rendered

exceedingly imperfect, also tended in a great measure to defeat the

bill.”

The Life of George Stephenson,

Samuel Smiles (1857)

Another notable defeat took place ten year later, when the Bill to

incorporate the Great Western Railway Company and its proposed line

from London to Bristol came before a parliamentary committee for

scrutiny and approval. The scheme’s promoters set to, to do

battle with the vested interests who opposed it, including

landowners who either objected to railways for the simple reason

that they were new or because, it was alleged, they would terrify

their livestock. Others hoped to bid up the price of the land

the railway would need to acquire. But the most vociferous

opposition came from rival transport interests, these being coach

companies, the Kennet & Avon Canal Company, and rival groups of

railway promoters. The contest lasted for 57 days and ended in

the Bill’s defeat.

When the Bill was resubmitted in the following year, Brunel, the

line’s chief engineer, presented the company’s case. His

cross-examination lasted for 11 days. Brunel was a master at

all aspects of his craft, including handling a parliamentary

committee. In paying tribute, an eye-witness observing his

performance during hearings in the House of Lords, had this to say:

“He was rapid in thought, clear in language and never said too

much or lost his presence of mind. I do not remember ever

having enjoyed so great an intellectual treat as that of listening

to Brunel’s examination.”

This second enquiry lasted for 40 days and ended in victory for the

Great Western railway, but at a cost of £90,000 in legal fees and

parliamentary expenses.

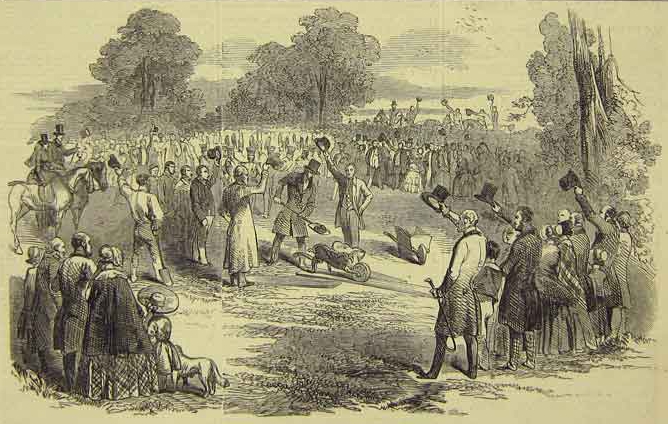

The ceremony of ‘cutting the

first sod’ ― this illustration is from the railway era.

A Bill that successfully negotiates the parliamentary hurdle

receives the Royal Assent from the monarch (last given in person by

the Sovereign in 1854), after which it passes into law as an Act of

Parliament. By it, its promoters were authorised to

incorporate a company to build the proposed canal, and were provided

with the necessary powers for that purpose. The ceremony of

‘turning the first sod’ could then be performed. |